Swiss National Museum/Tom Bisig

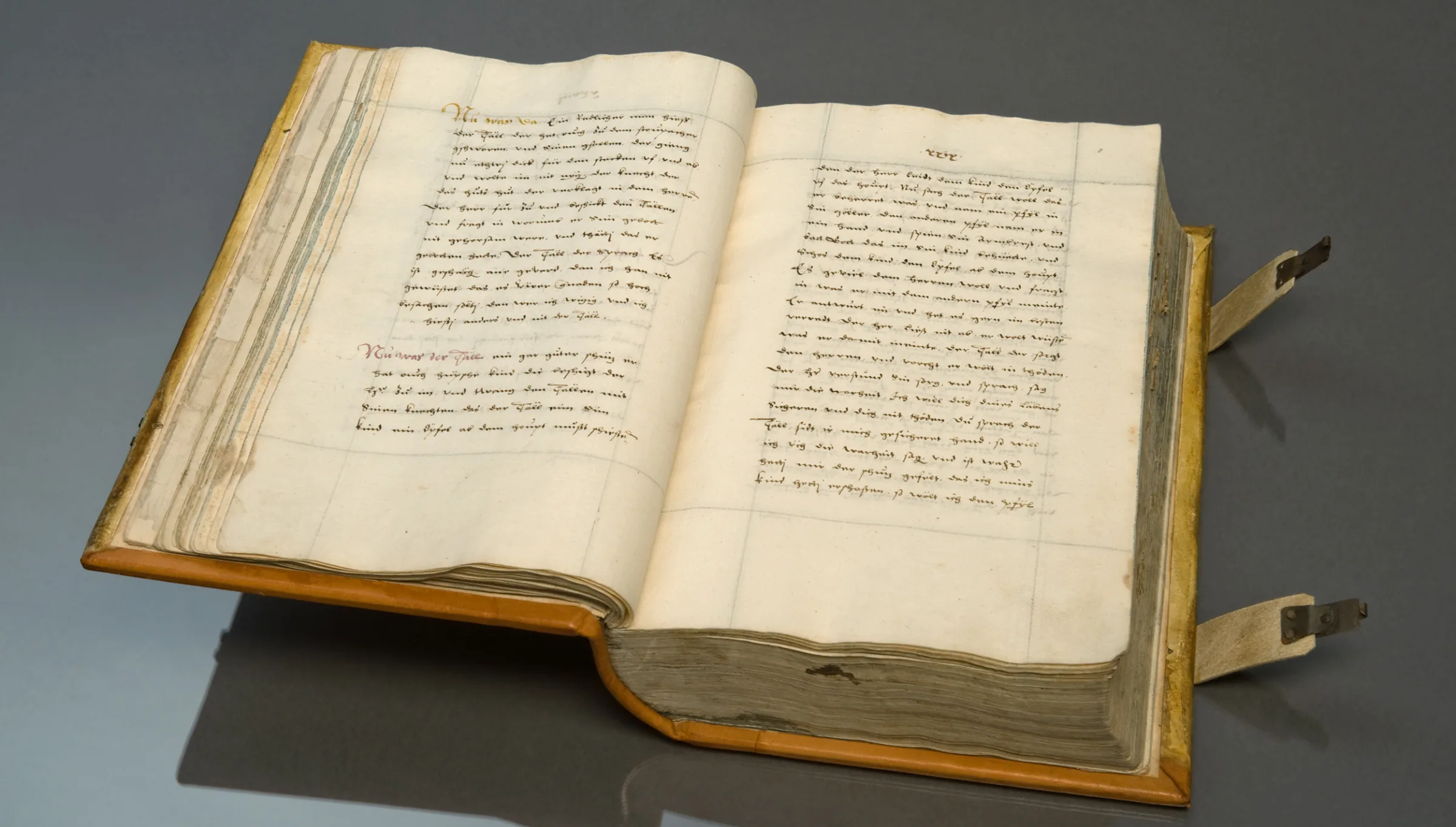

The White Book of Sarnen

Once upon a time, there was a hero named Tell. He was born in an office in Central Switzerland. Tell is an instrument, always working on behalf of whomever is telling his story.

‘Well, what an honest man was Thäll.’ With these words, Tell came into being in 1470, in a story we all know well: Gessler, Gessler’s hat, the apple shot, the leap on to ‘Tell’s slab’, the Hohle Gasse road, Gessler’s death, the oath on the Rütli, the Burgenbruch rebellion and expulsion of the bailiffs. Barely had he arrived in the world than Tell already had a mission. Not loosing off his deadly shot at the evil tyrant Gessler in the Hohle Gasse – this and all the other heroic deeds he performs in the story. Tell springs to life in the ‘White Book of Sarnen’, in a volume of official records, in an office. And like everything that is produced, decided, or put on record in an office, the White Book of Sarnen was not compiled without good reason, provocation, or a problem that somehow had to be resolved. Unterwalden had had a big problem since 1469 and, as is often the case with bureaucracy, it was complicated.

Unterwalden, together with all other states of the fledgling Confederacy, was outlawed. At the instigation of the Habsburg Duke Sigismund, Emperor Frederick III had placed the confederates under an imperial ban (Reichsacht). Habsburg wanted back all the rights in Aargau, Thurgau and Central Switzerland which had been lost to the Confederacy over the years, and he was willing to take them by force. Outlaws had no rights. Anyone was allowed to wage war against them. But a Reichsacht always laid down a challenge to the outlaws to set out their own legal position, and to substantiate it with legal documents. In 1470, the state secretary (Landschreiber) of Obwalden, the aptly named Hans Schriber, began recording all the region’s important legal acts in a book: deeds, privileges, contracts, court judgments, all made accessible via a detailed register, with pages left empty for subsequent entries. But the compilation of this information in the White Book of Sarnen shows one thing above all. Unlike Uri or Schwyz, Unterwalden had no ancient privilege for imperial immediacy (Reichsunmittelbarkeit) – that is, Uri and Schwyz were not subject to anyone other than the Roman Emperor directly – but only more recent imperial confirmations of an imperial immediacy which Unterwalden had never received.

TELL’S STORY BEGAN IN ROME

Tell’s story in the White Book of Sarnen began in ancient Rome, when all three territories – Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden – had been directly under the Empire’s control in antiquity. Later the foreign bailiffs (Vögte) arrived, and these men wanted ‘die lender vom rich bringen’, that is, to steal the lands from the Emperor, and from the Empire. What’s more, the bailiffs governed tyrannically – they were immoral, preyed on women, stole, and ultimately lost all legitimacy. Their brutal despotism reached its peak when a father was forced to take aim at his own son and shoot an apple off his head. For loyal subjects of the Emperor, it was almost a double duty to offer resistance, or to drive out or assassinate the bailiffs, in order to rescue the lands for the Empire. Viewed in that light, the Reichsacht of 1469 can really only be a misunderstanding – that is Tell’s mission. Would Tell have succeeded in his task, and won over the Empire’s legal experts, or would he ultimately have been thrown off track by the absence of any records of imperial immediacy? We don’t know. In 1474 Habsburg and the Confederacy went to war – not against each other, however, but on the same side, against a common enemy, Charles the Bold of Burgundy. Habsburg ultimately renounced his legal claims in the Swiss Confederation. The Reichsacht then became invalid. Tell had served his purpose before he even saw action.

But that’s not the end of the story. Good stories are flying carpets that can effortlessly transcend time and distance. Large portions of Tell’s story – with a hero called not Tell, but Toko, Palnatoki or Heming Aslakson – come from elsewhere, from Scandinavian folk tales, such as the story of the Danish kings, written by ‘Saxo Grammaticus’ at the court of the Bishop of Roskilde between 1185 and 1200. The shooting of the apple is even older; it can be found in the epic poem ‘Mantiq at-Tair’, thought to have been written in 1177 by the Persian Sufi and poet Fariduddin Attar.

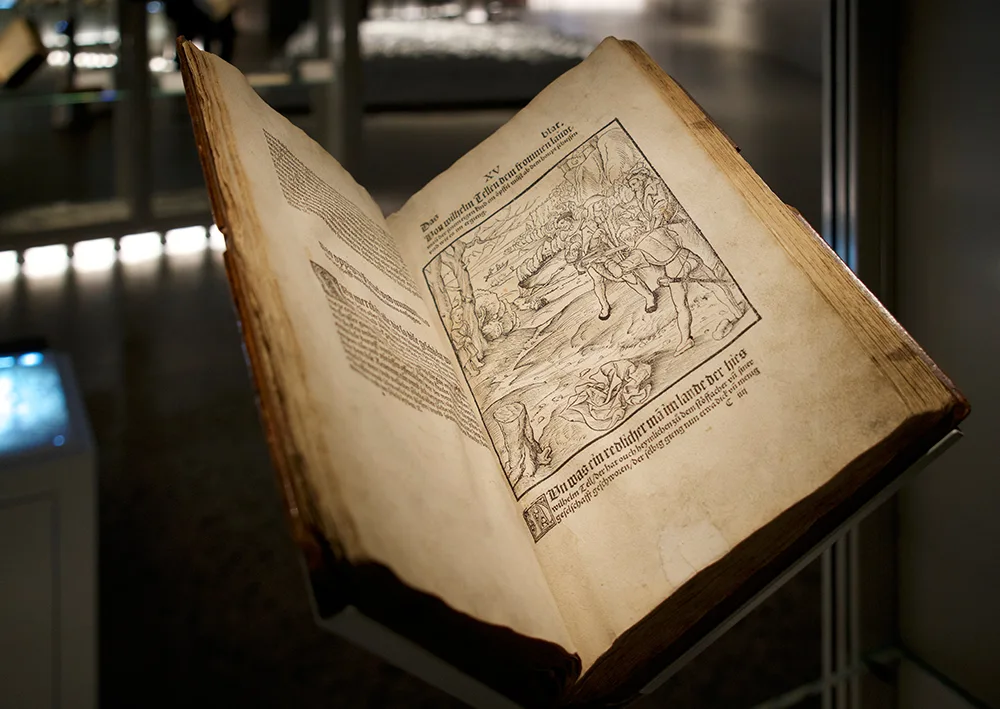

The oldest picture of William Tell, printed and reproduced in 1507 in Petermann Etterlin’s Chronicle.

Swiss National Museum

TERRORIST FROM THE MIDDLE AGES

Good stories don’t just fly smoothly and lightly like flying carpets; they also undergo modifications. In 1507 Tell appeared in print, in Petermann Etterlin’s ‘Kronica von der loblichen Eydtgnoschaft’ (Chronicle of the Swiss Confederation), illustrated with the shooting of the apple – the first ever picture of Tell. Soon, the one Tell had become three Tells, the three sworn founders of the Confederation, cast in metal in 1590 in the ‘Three Tells bell’ of Tell’s Chapel. In 1653, the three Tells resurface in Entlebuch. Three leaders of the rebellious subjects make an appearance in historical costume, dressed as the three Tells, and open fire on a delegation of Lucerne government officials. They’re not the only ones to have opened fire in the name of Tell.

There’s the French warship Guillaume Tell, launched in 1796, which fought in the Mediterranean for the French Revolution. Or John Wilkes Booth, the actor who assassinated Abraham Lincoln, incumbent president of the United States of America, at the theatre on 15 April 1865, and explained himself by saying he had done ‘what made Tell a Hero’. Or the anarchist Tatiana Leontieva, who attempted to assassinate the dreaded Russian Minister of the Interior at a Grand hotel at Interlaken in 1906. However, she shot an innocent French tourist instead. In court she too referred to Tell, as did, later on, the fighters of the Palestinian Liberation Front who in 1969 opened fire with machine guns on an Israeli passenger plane at Zurich Airport.

Among many other things, Tell is also a terrorist from the Middle Ages. Recounting a story sounds a friendly enough activity. But recounting it – and this is what makes the Tell story so hard to ignore – includes the license to kill.

Any person who invokes the story of William Tell – from Sarnen to Paris, Weimar to Washington, Interlaken to the Middle East – becomes the personification of a free peasant farmer from the Middle Ages. And one who comes out the winner in the end. He who purports to speak with the voice of the man with the crossbow casts himself in the role of the innocent victim of oppression. And at the same time, that of the valiant avenger who is fated to press the trigger. No wonder this medieval invention has become one of our top exports.

Where will the next Tell reach for his crossbow? ‘Pity a country that needs heroes’, goes a recent comment – referencing Bertold Brecht’s famous dictum ‘Unglücklich das Land, das Helden nötig hat’ – from Central Europe, where the issue of heroes is currently the subject of intense discussion. In Ukraine, monuments and street names that commemorate Stalin or Lenin are being removed. But should they be removed, and with what should they be replaced? Who knows whether, right now in Syria under Assad, in Egypt under Sisi or in Russia under Putin, Tell’s story is not about to be written once again?

The French ship Guillaume Tell was captured by British vessels off Malta in 1800, and promptly entered the British fleet as the HMS Malta.

Wikimedia