Wikimedia/Carole Raddato

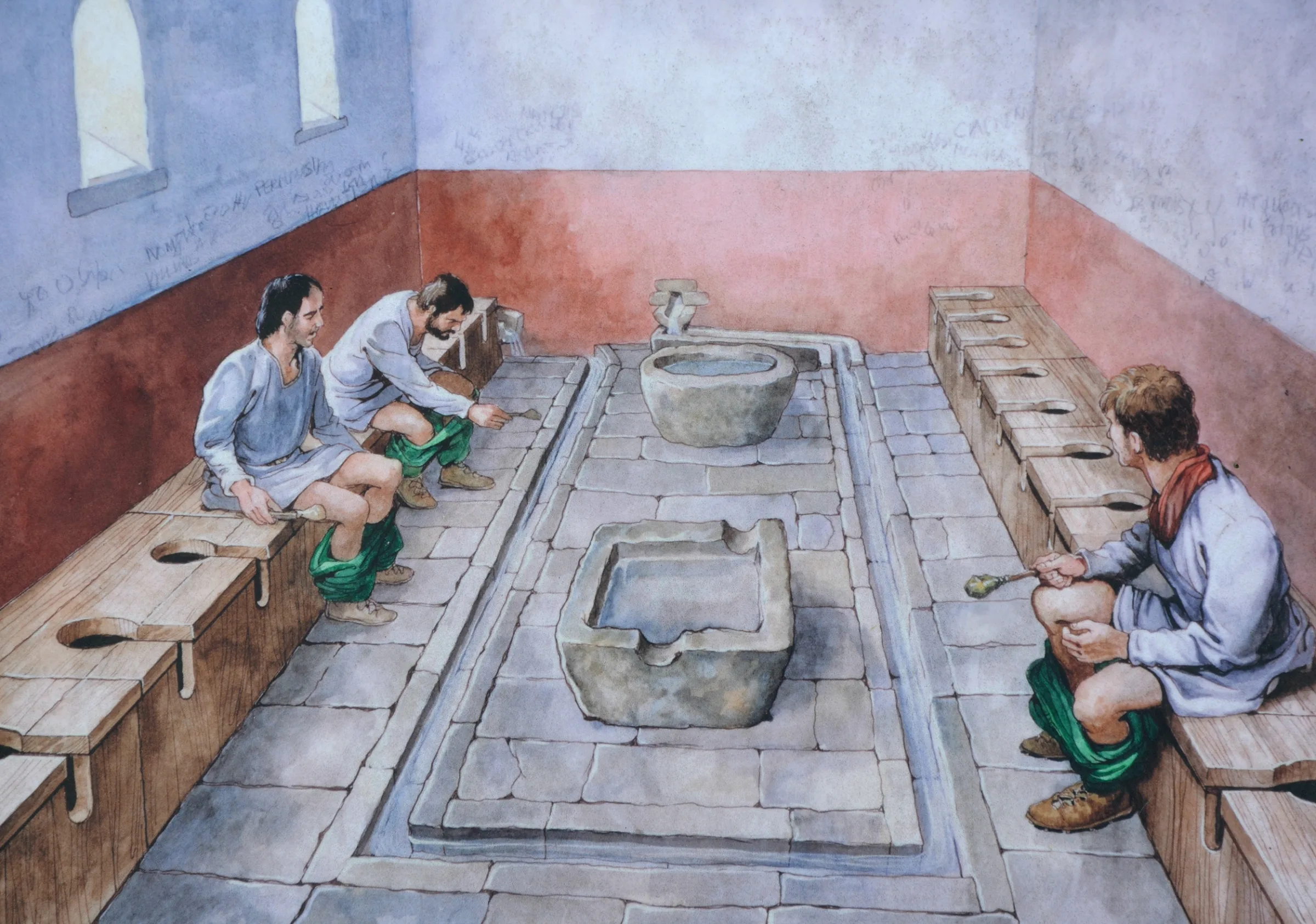

Pecunia (non) olet – Latrine archaeology: the dirty side of wealth

When the Emperor Vespasian (69-79 AD) was criticised for his new tax on urine – which was used for dyeing textiles – the Emperor is supposed to have laconically pointed out that money doesn’t stink, regardless of its source. For some researchers today, latrine archaeology (the study of toilet contents) is not just informative, but also a veritable treasure trove – whether stinking or not.

Archaeology can justifiably be described as probably the ‘dirtiest’ of the historical sciences. It relies on the extraction of its most important sources – found objects, deposits and remains of building structures and deposits – from the soil. The tools and procedures used by archaeologists on a dig are more like those of geologists than historians. But nonetheless, archaeology asks historical and sociological questions, and tries to answer them. If written and pictorial sources are available, these will also be taken into account. So, in methodological terms, archaeology as a discipline lies somewhere between the natural sciences and the humanities.

Archaeology rarely deals with structures damaged by chance – the evidence of natural disasters such as the volcanic eruption that buried people and houses in the Roman city of Pompeii – or deliberately hidden objects. Much more often, it deals with lost and discarded things: broadly speaking, waste. Waste is a mirror of the society that makes it, and the archaeologist’s task is to unscramble this distorted picture through the filter of its often very haphazard preservation, and the cultural distance of several hundred years.

One hundred or so latrines were excavated during digs in Lübeck city centre between 2009 and 2016, including this privy dating from the early 13th century. The ‘double seat’ of the lavatory is clearly visible in the centre.

Photo: Archäologie der Hansestadt Lübeck

‘Latrines’ are shafts or pits reinforced with walls or timberwork, which received the refuse from lavatories (‘privies’). These shafts, which were widespread in the late Middle Ages, had to be emptied at regular intervals. This dirty job was done by a separate occupational category in its own right, of lower social status, whose practitioners were also referred to, not without irony, as ‘gold diggers’. Today’s archaeologists are only rarely bothered by the smell of the erstwhile contents, since the composting process is usually complete – unless the latrine was below groundwater level, in which case archaeologists can justifiably speak of an ‘indescribable aroma’!

At first glance, it may come as a surprise how many of these finds ended up in a latrine. There are several categories here. On the one hand, kitchen waste and general garbage are deliberately disposed of in these ‘universal waste disposal units’. On the other, often things were simply lost in the ‘smallest room’. This could even be valuable items such as full money purses and the like – perhaps this was the origin of the proverbial spendthrift ‘pissing his money away’ (Geldscheisser in German). And lastly, things could be deliberately hidden in the latrine – more than one medieval murder victim has been found stashed in the toilet. However, the contents of a latrine are only a snapshot of the time after it was last emptied. The compost – and the finds contained in it – was usually spread on fields and in gardens as fertiliser.

A glimpse into the already emptied latrine pit in Lübeck city centre.

Photo: Archäologie der Hansestadt Lübeck

If we compare the contents of late-medieval latrines in the households of ordinary citizens and those of the aristocracy, the differences are not as great as might have been expected. In fact, there are few things that cannot crop up in both cases. Coins in large numbers, weapons and luxury goods such as silk, gold and corals have been found in the cesspits of citizens such as the Lübeck executioner. And the menu too seems to have differed less in the types of food, and more in the frequency and quantity of their consumption. In some cases, the same forms of cooking equipment and serving dishes have even been found. But there are certain differences. At castles such as the hunting lodge of Emperor Maximilian I (1508-1519) in Thaur, Tyrol, for instance, not only high-value objects, but also, unexpectedly, shards of window glass that was unusual for the time have been found in latrines. Evidently, other aspects also have a hand here. Firstly, the ruler was by no means the only inhabitant of the castle; he and his royal household were merely temporary guests. In his absence, a relatively middle-class standard of living may have prevailed. In addition, it is likely that the accoutrements of a hunting lodge and the equipment kept there would perhaps be kept deliberately more country-style than elsewhere in the imperial milieu, and the most precious items, regardless of their state, would seldom have found their way into the latrine.

Latrines are also treasure troves of everyday objects, such as this purse from a latrine in Lübeck city centre.

Photo: Archäologie der Hansestadt Lübeck

Convenient travelling cutlery – known as a ‘Mundzeug’ (mouth tool) – consisting of knife and ‘eating pick’, from the latrine at Thaur Castle in Tyrol. The blade of the knife shows traces of the inlaid smith’s mark H(H), indicating the workshop of imperial armourer ‘Hans aus Hall’ Sumersperger (workshop in Hall in Tirol 1492-1498).

Photos: Andreas Blaickner, Institute of Archaeology, University of Innsbruck