Musée d’histoire de la Chaux-de-Fonds

The dangerous business of Jules Bloch

Swiss industrialist Jules Bloch exported ammunition components to France during the First World War. Germany attempted all kinds of intrigues to put an end to his dealings.

From 1915 to 1918, Swiss companies churned out ammunition components and sold them to the warring nations. Among the major producers supplying France was Jewish industrialist Jules Bloch. Before the war Bloch, a Swiss entrepreneur, had been active in the steel and watchmaking industry, but when war broke out he adapted production and orders at his Jura and Neuchâtel watch factories to the new circumstances, and from then on had them producing detonators for artillery projectiles. Jules Bloch travelled on his own train from Neuchâtel to Moutier, from Delsberg to La-Chaux-de-Fonds and from Biel to Lausanne, where he signed agreements with manufacturers, loaded the cargo into goods wagons and organised the railway convoys that transported the munitions to France. Over the course of four years, he sold the French army weaponry worth almost 85 million Swiss francs – a goldmine that kept a whole raft of small local industries in the Jura Arc afloat throughout the war.

Jules Bloch’s detonators being packaged in intentionally mislabelled boxes to allow for transportation ‘under the radar’.

Musée d’histoire de la Chaux-de-Fonds

Loading goods wagons with ammunition components.

Musée d’histoire de la Chaux-de-Fonds

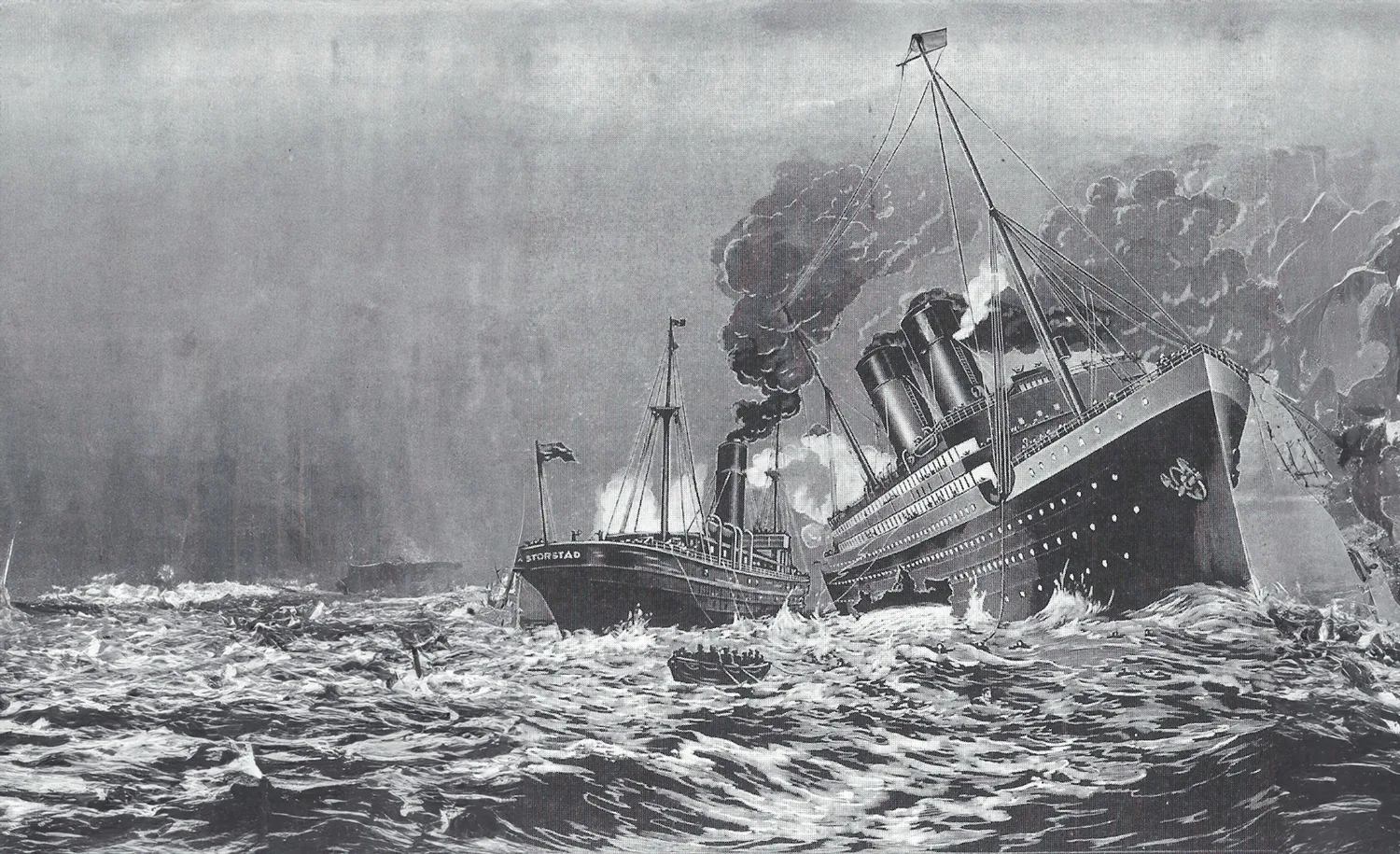

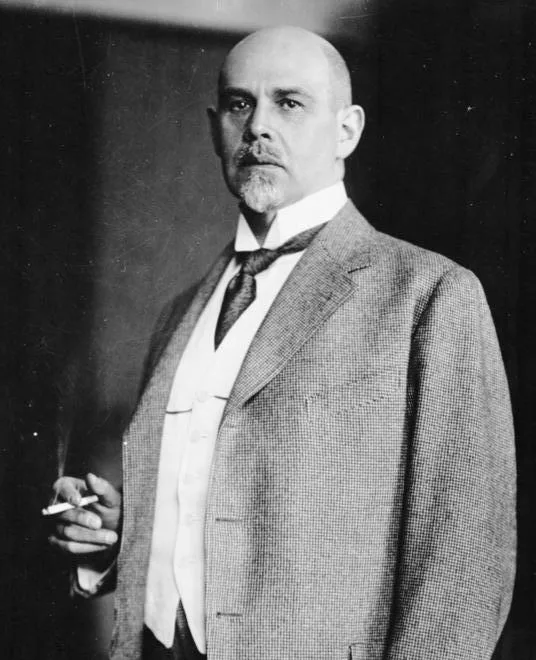

It was these business relationships that brought Bloch into contact with Albert Thomas, the French Minister of Armaments, who later visited the Neuchâtel industrialist on a number of occasions. Inevitably, this business activity attracted the attention of the German secret service. Germany’s influence in Switzerland was manifested in a number of ways. A lot of Swiss companies had been taken over by private German companies. Although takeovers are not unusual in a free market economy, in view of the ongoing war there were grounds for suspecting that these acquisitions had been undertaken with the intention of instigating a trade war. Behind a number of Swiss factories – among them producers of aluminium and nitric acid in Neuhausen, Rheinfelden and Chippis, and ferrosilicon producers in Olten, Aarburg, Gösgen and Augst-Wyhlen – was the powerful Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG), headed by Walther Rathenau. The high-ranking official of the Prussian Ministry of War was in charge, up to April 1918, of the Kriegsrohstoffabteilung, the department responsible for procuring the raw materials needed by the military. The founding of an offshoot of AEG, called Metallum AG, with its headquarters in Bern, had the stated aim of simplifying industrial transactions between Switzerland and Germany. Through Metallum AG, repeated attempts were also made to damage the armaments manufacturer Bloch. Metallum was managed not only by Walter Rathenau, but also by the directors of the firms Metallgesellschaft, Metallbank and Metallurgischen Gesellschaft, making it effectively a German group of companies operating in Switzerland. The company was in direct contact with the German legation and the Reich secret service, whose office in Lörrach, just outside Basel, was responsible for special missions in Switzerland.

Walther Rathenau

Wikimedia / Federal Archives, Image 183-L40010

From 1917 Metallum intensified its machinations against Bloch, attempting to discredit some of his suppliers in order to bring him into disrepute among his French customers. Although these schemes failed, they created a very negative image of Jules Bloch, who was portrayed as a kind of ‘millionaire king’ wallowing in the lap of luxury. The fact that Bloch had on several occasions contested supplementary tax demands by Switzerland’s Federal Tax Administration didn’t help his reputation. He claimed that, due to the precarious war situation and the current orders in his factories, he had been unable to calculate his earnings correctly. In February 1918 the Swiss tax authorities – after the military defeat of Russia, no doubt fearing a German victory and thus Bloch’s ruin – slapped Bloch with a two million franc tax bill. In the months that followed, however, the tax department, influenced by the impression that Metallum was setting out to damage Bloch, and by the increasingly parlous state of Switzerland’s economy, started asking questions about the armaments manufacturer’s actual profits, and launched an investigation. From the findings it was concluded that the Neuchâtel entrepreneur owed the tax department the enormous sum of twenty-two million Swiss francs. While Jules Bloch was trying desperately to fend off this tax demand, anonymous allegations of fraud were made against him. The accusations led to a search of Bloch’s office, which uncovered evidence of an attempt at bribery. The fact that an employee of the Swiss Federal Tax Administration was directly involved made things even more awkward.

Production of ammunition components at the firm Piccard, Pictet & Cie Geneva. The production of munitions, which had been increasing since 1915, quickly led to a labour shortage in the metalworking and machinery industry. Women were increasingly employed in this traditionally male-dominated industry.

Swiss National Museum

On 8 August 1918, Bloch was finally arrested and placed in pre-trial custody at Bois-Mermet prison in Lausanne, before the Federal Supreme Court found him guilty in January 1919. He was sentenced to eight months in prison. In addition, he was required to pay 2.7 million francs in taxes and a fine of 10,000 francs. As he was unable to get together the full amount in cash, Bloch was forced to sell some of his assets. This included, in particular, a house on a plot of land outside Geneva. Not long afterwards, the Federal Government offered the parcel of land to the International Labour Organization, which later established its headquarters there. The first Director-General of the ILO was none other than Bloch’s old friend Albert Thomas, the French Minister of Armaments.

Of course, little is known about the details of the tax negotiations that took place while the industrialist was behind bars. However, we do know that Bloch enjoyed many privileges during his imprisonment. He was allowed to receive visits from his family, and from his secretary, notary and lawyers, with whom he continued to work, and to go into the city for a trip to the tailor or a meal in a restaurant.

When the First World War, and the propaganda war waged at Bloch’s expense, ended he returned to a more conventional business activity and, in particular, became deputy director of Metallwerke AG in Dornach in 1925. Jules Bloch died in 1945. He had lived to see the assassination of Walther Rathenau, who had been appointed German Foreign Minister in 1922 and was shot dead the same year by members of Organisation Consul, an ultra-nationalist and anti-Semitic underground group.