Katrin Brunner

Banged up in the schoolhouse basement

In Niederweningen, Zurich, the basement of the schoolhouse was once used as a prison. Not everyone was happy about it.

Criminal energies and indiscipline don’t stop at the level of a village community. What to do with violence-prone husbands, thieves, or soldiers who shirk their military duties? In 1850, six years after the primary school building was completed, the village of Niederweningen in the Canton of Zurich decided on an unorthodox use for the building’s underground rooms, and set up the village jail in the school basement. The previous tenant, Müllerüeli, was not best pleased with this decision, as he had just laid down a barrel of his best wine, vintage 1834, in the wall of the building. The two parties agreed on a solid wooden wall to keep the resident villains separate from the wine.

The crimes with which the people detained in the village slammer were charged were relatively tame by today’s standards. One youth had to spend a day in the holding cell and eight days on the Schandbank, a bench where malefactors were required to sit on public display, for stealing ten francs. Another student was sentenced to four days in prison for truancy and begging. After a brief detention in the cellar, an unruly and violence-prone father was referred to the local governor. Like most of the prisoners, in fact. The village jail was never intended for a lengthy stay. 41 years later, the community also wanted to use the basement as a storeroom for the local hearse. Müllerüeli still had wine in the cellar, and once again was not keen on the idea. It is not known whether his barrel of wine was still the same 1834 vintage.

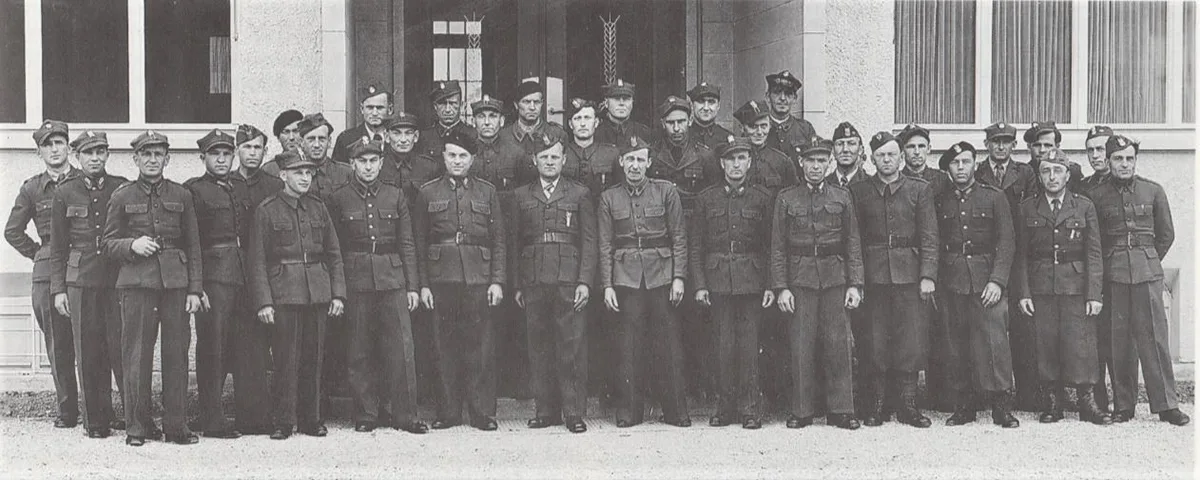

Interned Polish nationals in Niederweningen in 1943.

Bucher Guyer Archive

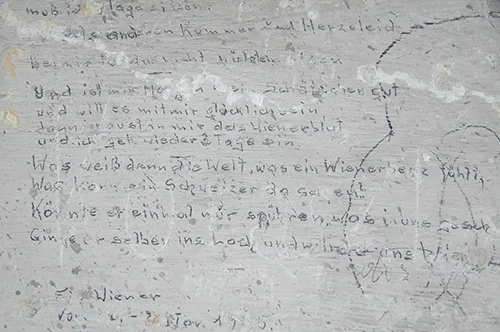

During the Second World War, Swiss soldiers were quartered in the schoolhouse in the holidays. Dozing off on the watch, excessive drinking when off duty and other offences resulted in disciplinary sanctions. The little room with the window to let in fresh air and light, which was more a slit than a proper opening, was still used as a detention cell. The soldiers banged up there had plenty of time in which to adorn the walls with one or other original decoration.

“…and if my sweetheart is good to me tomorrow, and if she is happy with me, then the Viennese spirit in me…and I go back in for three days…”

“…what can a Swiss man say to that? If he could just feel what’s going on inside us. If he were to go into the hole himself…”

These words, still legible today, were written by an unknown hand in November 1945. In the gloomy room, barely seven square metres, there was little else to do apart from write poems and doodle portraits of beautiful – perhaps fantasy – women on the walls.

“As children, we didn’t really have much idea what they were down there for. But they kept asking us to organise cigarettes, chocolate or cookies,” remembers Rudolf Hauser, who was in and out of the schoolhouse as a primary school pupil between 1943 and 1949. The scrawled eagle of the 2nd Polish Rifles Division shows that interned Polish soldiers also found their way into the building from time to time. In view of the horrors already experienced by the 50 to 100 Poles who were interned in Niederweningen between 1942 and 1946, their incarceration in the tiny basement cave was probably more of a comfortable detention. The Poles were part of the largest border crossing since General Bourbaki crossed the Swiss border with around 90,000 soldiers in 1871, fleeing from the advancing Prussian troops in the Jura.

In June 1940, the Bundesrat, Switzerland’s federal council, allowed 30,000 French and around 12,500 Polish soldiers, as well as 7,000 civilians, to enter Swiss territory. They were all fleeing from the advancing Nazis. This huge number of refugees was welcomed and dispersed to various internment camps, including Niederweningen. While the French left Switzerland after a short time, the Poles stayed until the end of the war.

Nothing is known about the fate of the Viennese spirit. Whether he found his love, in Niederweningen, Poland or somewhere else, will remain forever hidden in the depths of global history.

Poem on the wall of the schoolhouse basement in Niederweningen.

Katrin Brunner

Polish internees with a woman from Niederweningen.

Album of Getrud Bucher