Kockum Sonics AG Dübendorf

Sirens, compressed air and spine-chilling howls

Sirens wailing!? A worried glance at the clock. 1:30 p.m. precisely. Aha – siren test! Everything’s fine! Switzerland’s annual siren test takes place on the first Wednesday in February. But how long have we had sirens in Switzerland anyway? What’s the history of this hair-raising means of communication? This brief digression on the occasion of our annual national wail tells all.

Sirens form part of an array of archaic means of communication for alerting the populace to a threat. Many hundreds of years ago, the cry of ‘Fürio!’ (‘Fire!’), the ringing of bells, drumbeats or the sounding of the fire horn summoned able-bodied men to fight the fire, and warned the population at large of a calamity. Watchtowers (‘Hochwachten’ or ‘Chutzen’) are part of a similar tradition. In Switzerland, this network of warning systems, at locations that were visible from afar, signalled an enemy attack and was used to mobilise military forces from the 15th century onwards. Messages were passed along using fire and smoke signals, sometimes aided by the firing of canon and the ringing of church bells when visibility was poor.

Frenchman Charles Cagniard de la Tour is considered the inventor of the siren. The device created by Cagniard de la Tour, an engineer and physicist, dates from 1819; it functioned with compressed air, and helped him measure audio frequencies. Using his invention, the Frenchman studied the propagation of sound in liquids. When naming his device, Cagniard de la Tour turned to Greek mythology. Sirens are mythical creatures, usually female, who use their captivating singing to lure sailors to their deaths in dangerous shallows. What the inventor found appealing about the wailing of his own siren remains open to question.

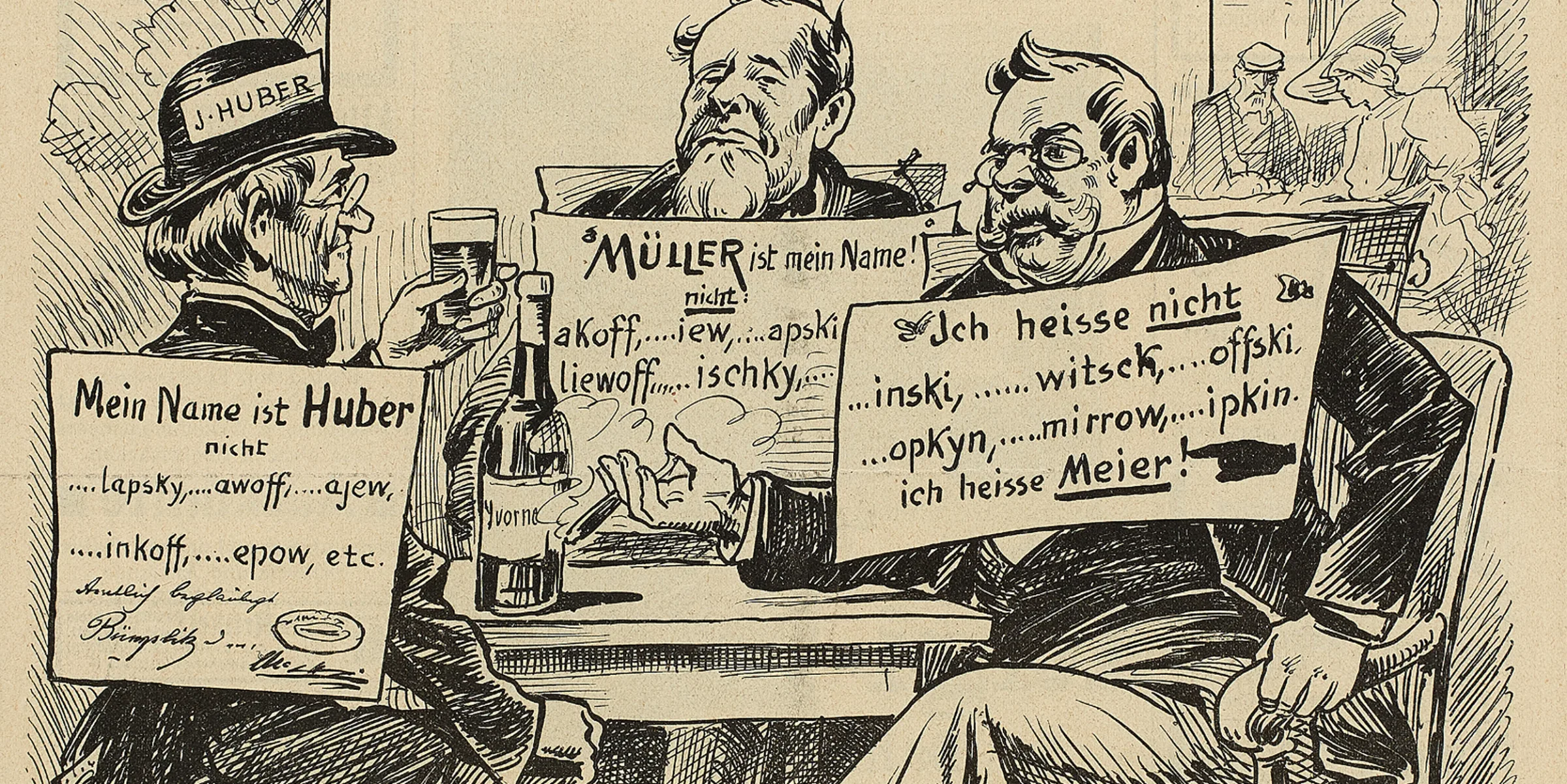

But it was a long time before the siren was used for alerting purposes. Research in Swiss newspaper and magazine databases suggests that from the First World War onwards, sirens were occasionally used in Switzerland for fire alarms. For example, on 20 June 1914 the Engadiner Post newspaper reported on the use in a fire drill of a ‘siren recently purchased by the municipal authority’. The Oberländer Tagblatt reported on 10 April 1920 that the fire department in Thun had conducted an initial trial. However, the siren, installed on one of the turrets of the castle, gave an underwhelming performance. ‘The alarm of this motorised siren is not powerful enough to rouse the people from their sleep, nor is it able to penetrate effectively and adequately through daytime noise.’

Sirens are direct descendants of the watchtowers (‘Hochwachten’ or ‘Chutzen’) of previous centuries. From the mid-15th century onwards, the watchtowers acted as a warning system and were used to mobilise military forces. If visibility was poor, the signals were passed along via a mortar blast. Le signal de Cerlier (Erlach), watercolour by Caspar Wyss, 1793.

Museum of Communication, Bern, BE/Erl 0002

Danger from the air

After Hitler seized power in 1933, Europe entered a phase of military re-armament. The tense political situation in Europe and the Spanish Civil War led to aerial combat weapons being modernised throughout Europe. As a result, the civilian population was increasingly at risk from aerial warfare. From 1934, Switzerland intensified its efforts to put in place passive air-raid protection for its civilian population, and the Federal Council (Bundesrat) issued a first resolution to this effect. This then provided the basis for the ‘Verordnung betr. Alarm im Luftschutz vom 18. September 1936’ (Ordinance on air raid warnings of 18 September 1936), whose purpose was to give the public timely warning of impending air raids. The regulation ordered ‘local authorities with an obligation to provide air raid warnings’ to install fixed and mobile sirens, and handled the associated costs.

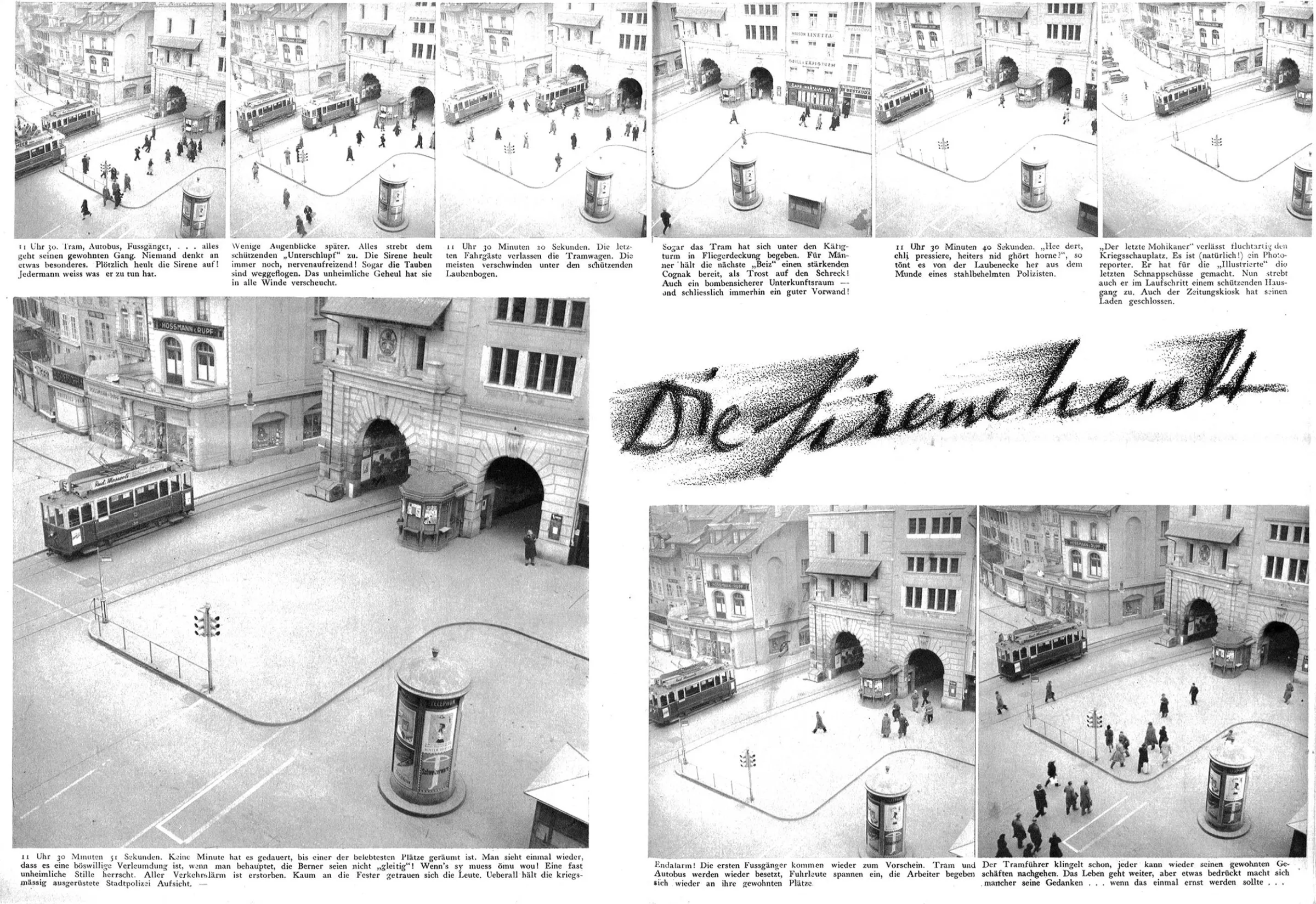

Siren test in Bern, late 1939. Pedestrians seek shelter under the city’s medieval Käfigturm, and one of the tram drivers also seeks cover there with his vehicle.

Die Berner Woche

During World War II, air raid warnings and the accompanying fear became a commonplace experience near the borders and in the Swiss Plateau (Mittelland). On 25 April 1945, the sirens wailed a total of nine times in Zurich. The danger was real: Swiss airspace was violated in 6,501 incidents, and bombs were dropped 77 times, with a total of 84 deaths reported. While the war was still going on, Bern company Gfeller AG started offering the first technical solutions for controlling and activating multiple sirens simultaneously via a telephone line. The advantage of this, particularly in urban areas, was that alarms could be sounded sooner.

With the dropping of the atom bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, aerial warfare achieved a new dimension of destruction. The nuclear threat would go on to shape the next few decades of aerial defence and civilian protection in Switzerland. But it would still take some time before these fears became firmly entrenched among the general public. In the 1950s, the Swiss people had only a limited understanding of the concerns facing civil defence authorities. In 1952, for example, a compulsory scheme to install air raid shelters in existing buildings fell flat at the ballot box. It wasn’t until 1959 that voters incorporated a revised civilian protection article into the federal constitution. The suppression of the Hungarian uprising by Soviet troops in 1956 and the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 really brought home the dangers of the Cold War, and accelerated the organisation of civilian protection in the 1960s. From the start of that decade onwards, the nuclear threat led to a boom in shelter construction based on newly created laws.

Air raid warnings weren’t always just drills. This postcard vending machine in Renens, Canton of Vaud, was damaged on 12 June 1940 by fragments of a Royal Air Force bomb. Air raid warnings were a daily occurrence in Switzerland during World War II, and it wasn’t always just property that got damaged. From 1939 to 1945, a total of 84 people died in bombings in Switzerland.

Museum of Communication, Bern, Paw 0062

Concerns about the bodies of water held in reservoirs

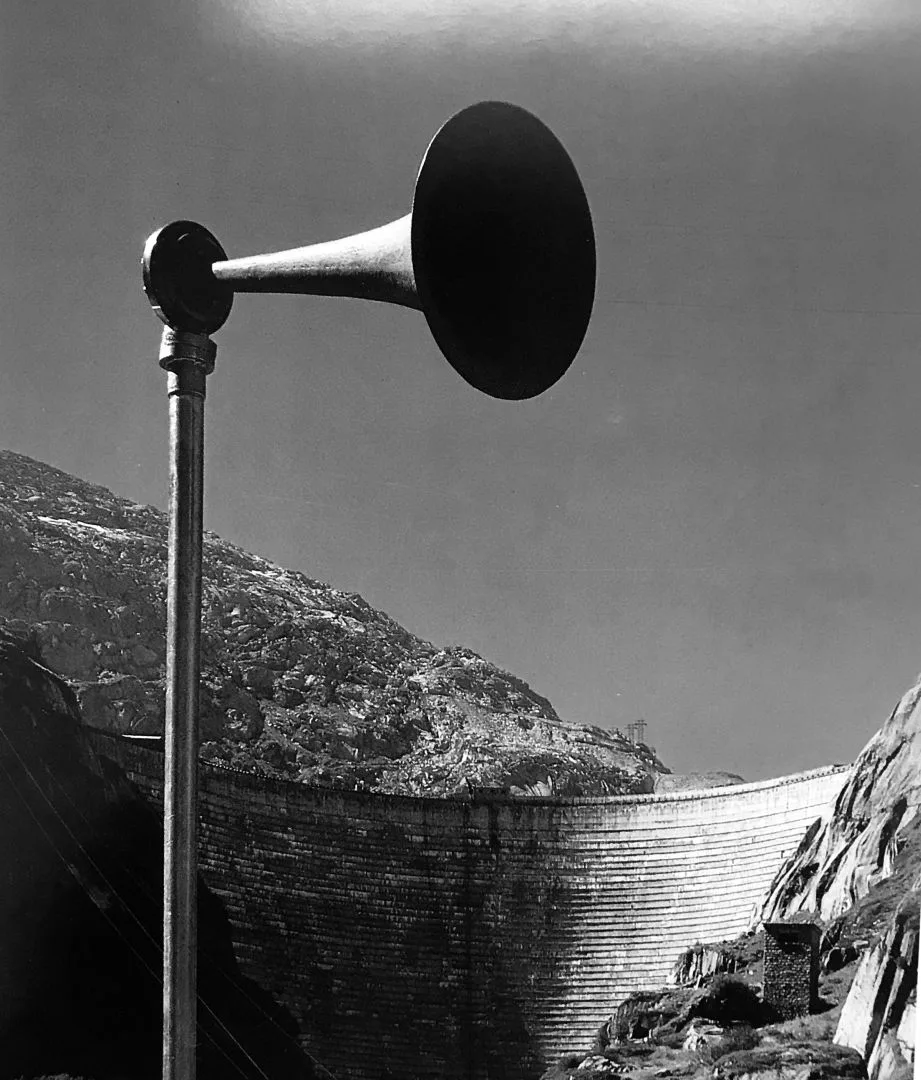

While concrete was being vigorously mixed all over the place, less attention was given to the issue of actual alerts. The water alarm was an exception. Since World War II, the military had considered the bombing of dam walls to be the chief threat. In some places, the areas directly below these constructions were equipped with alarm systems. But the Vajont Dam disaster in 1963, which left more than 2,000 dead – a landslide in the Italian reservoir caused a tsunami to overtop the dam – then made it clear that reservoirs could pose a danger to the populace even in peacetime. In response to the catastrophe in Italy, the revision of the ‘Talsperrenverordnung vom 10. Februar 1971’ (Regulation on dams of 10 February 1971) stipulated that water alarm systems must also function during peacetime. The ‘local area’ below the concrete dam was increased from a 20-minute radius to two hours. Areas that were at risk from a flood wave within two hours now had to have a siren system in place. Starting in the 1960s, the Department of Defence relied on the ‘System SF 57’, made by Autophon AG from Solothurn, for activating a water alarm. The alarm was triggered manually, and not by equipment such as measuring devices or sensors. The sirens were controlled via dedicated lines. The actual wailing noise was made by ‘Tyfon’ sirens from Ericsson AG, originally a Swedish firm. They functioned with compressors and had an operational autonomy capacity of 30 days.

Grimselsee Dam, ‘Tyfon’ siren. Probably 1970s. From World War II onwards, water alarm systems were put in place below many dams. Initially, it was feared there could be air raid attacks on the dam structures. From the 1960s, the threat was more likely to come from tsunamis associated with landslides or earthquakes.

Kockum Sonics AG Dübendorf

Radiation fears

Switzerland found out early on about the dangers of nuclear energy. In 1969, the underground experimental reactor at Lucens, Canton of Vaud, was destroyed when the nuclear fuel rods melted. Radioactivity leaked out. From the late 1970s, the cantons and municipalities affected by these power sources sought to set up an alert system around the newly built nuclear power plants (NPPs). Where the existing civil defence sirens were not adequate for area-wide alerting, new systems were put in place. The ‘Federal Nuclear Safety Department (ASK)’ issued technical guidelines for the alarm sirens. Within a radius of approx. three kilometres, referred to as ‘Local area 1’, NPP operators could trigger a radiation alarm directly. In the adjacent ‘Local area 2’, alert status was determined by weather conditions, or wind direction. However, it would take some time before the alarm system functioned properly in ‘Local area 2’! On 1 June 1987 the Freiburger Nachrichten newspaper reported on the installation of these sirens in Murten, with the company Bernische Kraftwerke AG, as operator of the Mühleberg nuclear power plant, required to cover the costs. In the same article, the paper was critical of the fact that the residents of the Freiburg municipalities in ‘Local area 2’ had not yet received any sort of information sheet on what to do in the event of a radiation alarm. Elsewhere, people were quicker off the mark. In the cantons of Solothurn and Aargau, these letters had been sent out in 1978-1979.

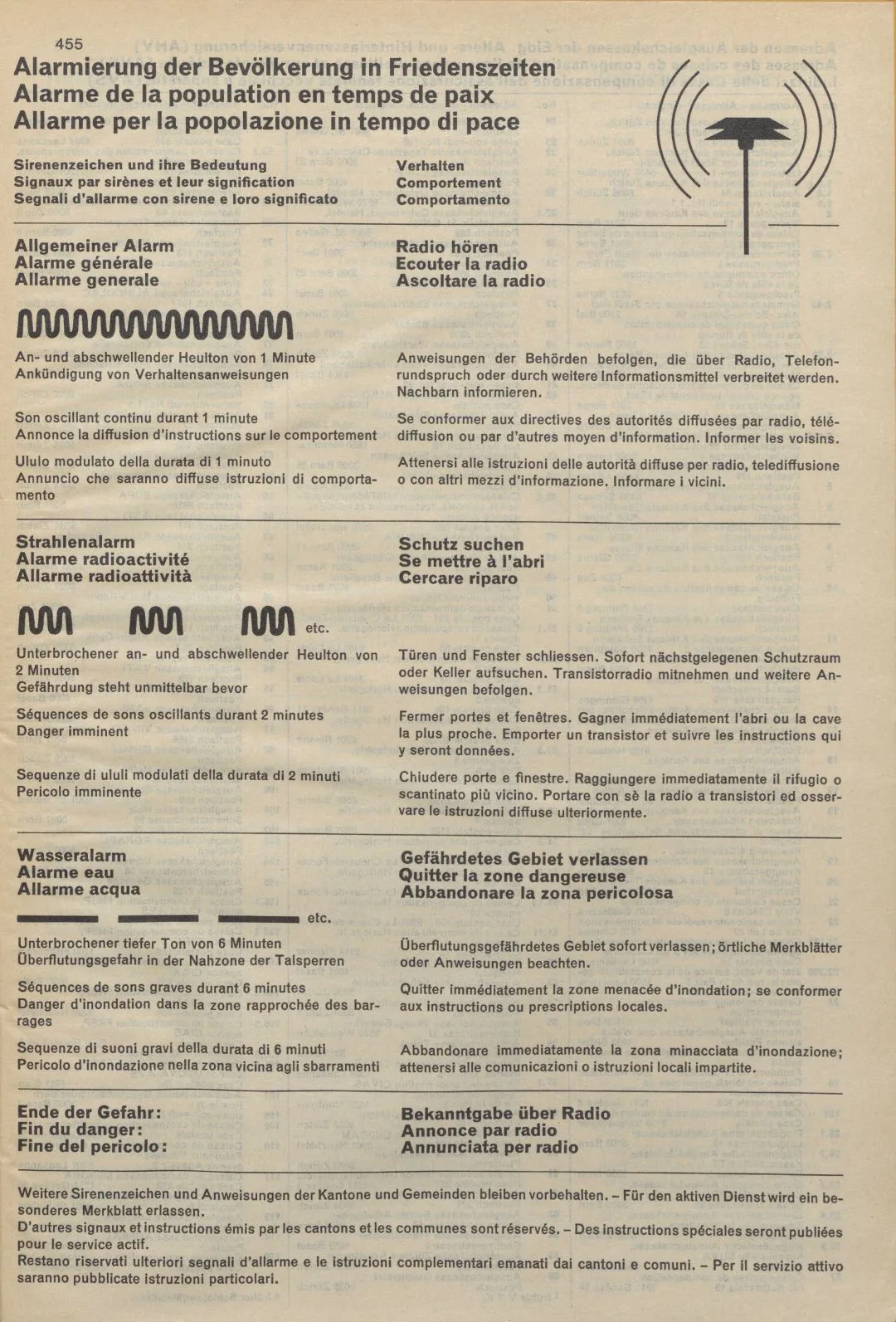

Starting in 1980, there was a separate page in the phone book to help people decode the siren signals.

PTT Archive

In 1969, the government distributed the little red book Zivilverteidigung (civil defence) to all households. In this piece of contemporary Cold War history, you could read how to (supposedly) survive a nuclear war. The marmot graphic sums up the strategy in simple terms: sound the alarm, and then disappear underground as fast as you can.

Federal Department of Justice and Police

Anyway, from 1980 onwards the recommended course of action in the event of a radiation alarm could be looked up in the telephone book. For a general alarm the advice was ‘listen to the radio’, for a radiation alarm ‘seek shelter’ and in the event of a water alarm, ‘leave the danger area’. These pages in the telephone book also reflect the great collective fears of the 1980s. Some level of people’s subconscious probably associated the general alarm with ‘the attack by the USSR has begun!’, and the radiation alarm with ‘the nuclear apocalypse is on its way!’ Then, in 1986, the Chernobyl reactor disaster made it plain that fears about the civilian use of nuclear energy were not unfounded. The same year, the huge fire at a chemicals factory in the Schweizerhalle industrial area demonstrated that raising the alarm among the general public in Switzerland was still not perfectly orchestrated. The siren alarm came late, and was not heard everywhere – in Grossbasel, some of the sirens were offline for inspection at the time.

The birth of the national test alarm

From the 1980s onwards, civil defence authorities endeavoured to create a denser alarm network and standardised test alarms across Switzerland. The sirens wailed simultaneously across the country for the first time at 1:30 pm on Wednesday 1 September 1982. The outcome of the drill was quite underwhelming. In the cantons of Jura, Valais, Vaud, Obwalden and Graubünden, the alarm systems were not set up ready for operation, and the wailing mechanisms remained silent. In 1988 the federal government made the siren test mandatory. From 1981-1990 a siren test was carried out twice a year, on the first Wednesdays of February and September. After that, a parliamentary initiative – which related to the good condition of the sirens – reduced this to a single alarm.

Siren operation box for directly activating a fixed pneumatic siren, for the Tyfon KTG-10 model. The buttons reflect the great collective fears of the 1980s.

Museum of Communication, Bern, IKT00747

Alerts 2.0

Since about the turn of the millennium, the remaining pneumatic sirens have been gradually replaced by electronic systems which, thanks to the use of batteries, are self-powered. The alarm market is divided among a handful of companies, such as Kockum Sonics AG in Dübendorf, which emerged out of Swedish firm Ericsson AG, and Sonnenburg Swiss AG in Uzwil. Today, the approximately 5,000 fixed sirens are connected to a uniform control system and can be triggered centrally using ‘Polyalert’. The police in each individual canton are usually responsible for this. Working together with the cantons and other partners, the Swiss Federal Office for Civil Protection (FOCP) developed the redundancy-proof siren remote control system in 2009-2015. The alert system, which is rated as very failsafe, is based on the Polycom network, the secure national radio system operated by the authorities and organisations responsible for rescue and safety. Since 2018, warnings and alerts have also been made public as push notifications through the Alertswiss app, and online via social media and on the Alertswiss website. But in case things get really bad, it’s still advisable to keep a battery-powered VHF radio in your house or apartment – it means that even after the power and telecommunications networks have gone down, you can still get the instructions and information provided by the authorities. The emergency transmitters can even penetrate two metres of reinforced concrete without difficulty…

Current standard in Switzerland. The Delta electronic sirens from Kockum Sonics in Dübendorf. This is an installation on Lake Zurich.

Kockum Sonics AG Dübendorf

If a siren alarm isn’t a drill, you need to listen to the radio. Emergency radio with solar panel and hand crank for autonomous operation, 1980s.

Museum of Communication, Bern, IKT00062

The Federal Office of Civil Protection (BABS) also provides public alerts via the Alertswiss app. However, a prerequisite for the app’s operation is a functioning power supply and telecommunications system.

BABS