Smuggling in the tri-border area

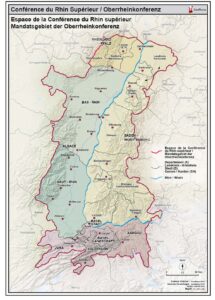

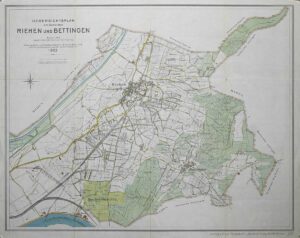

Especially in times of scarcity, smuggling has been an important activity, and for people in the tri-border area where Switzerland meets Germany and France it has been no different. The complicated lines of the border made smuggling even more attractive here.

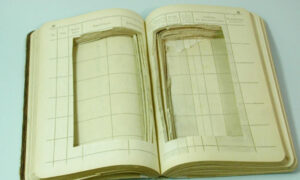

Smuggler’s shoe with a hollowed-out sole, and a book repurposed for smuggling. Both objects were collected in the early 19th century by a customs officer serving on the French border in Allschwil. Allschwiler Heimatmuseum

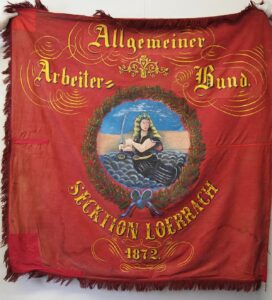

SPD flag brought to safety

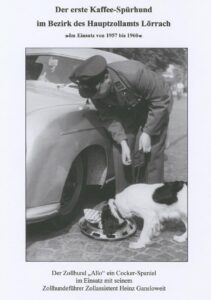

Dreiländermuseum Lörrach (Three Countries Museum)

The Dreiländermuseum Lörrach regularly stages exhibitions on topics relating to the three countries. The Museum devoted a special exhibition, which was accompanied by a booklet, to the subject of border history and smuggling in the tri-border area.