Wikipedia

Jakob Fugger – Money and spirit around 1500

Augsburg: a descendant of a rural weaver became Europe’s most prominent merchant, mining entrepreneur and banker, despite the Bible’s prohibition of usury. A biography sheds light on an era of history – and vice versa.

When Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, died in 1519, he owed the Augsburg merchant and banker Jakob Fugger (1459-1525) around 350,000 guilders. To avoid losing this investment, Fugger had to help Maximilian’s grandson, Charles V, ascend the throne. Charles’ unanimous selection by the Electors required exorbitant bribes, to the tune of 851,585 guilders, to smooth the way. Jakob Fugger, nicknamed ‘the Rich’, put in 543,385 guilders, around two thirds of the sum. The remainder was contributed by the Welser banking family and three Italian companies.

This was more than just a favour. In return, Fugger obtained the right to continue mining metals – silver and copper – in the Tyrol as a money-spinner. The largest known deposits in Europe at the time provided the basis for further mining companies, and also for banking activities, particularly with the Habsburgs, but also with the popes. Fugger also had access to Spanish business operations. Charles V ruled over a realm where the sun never set.

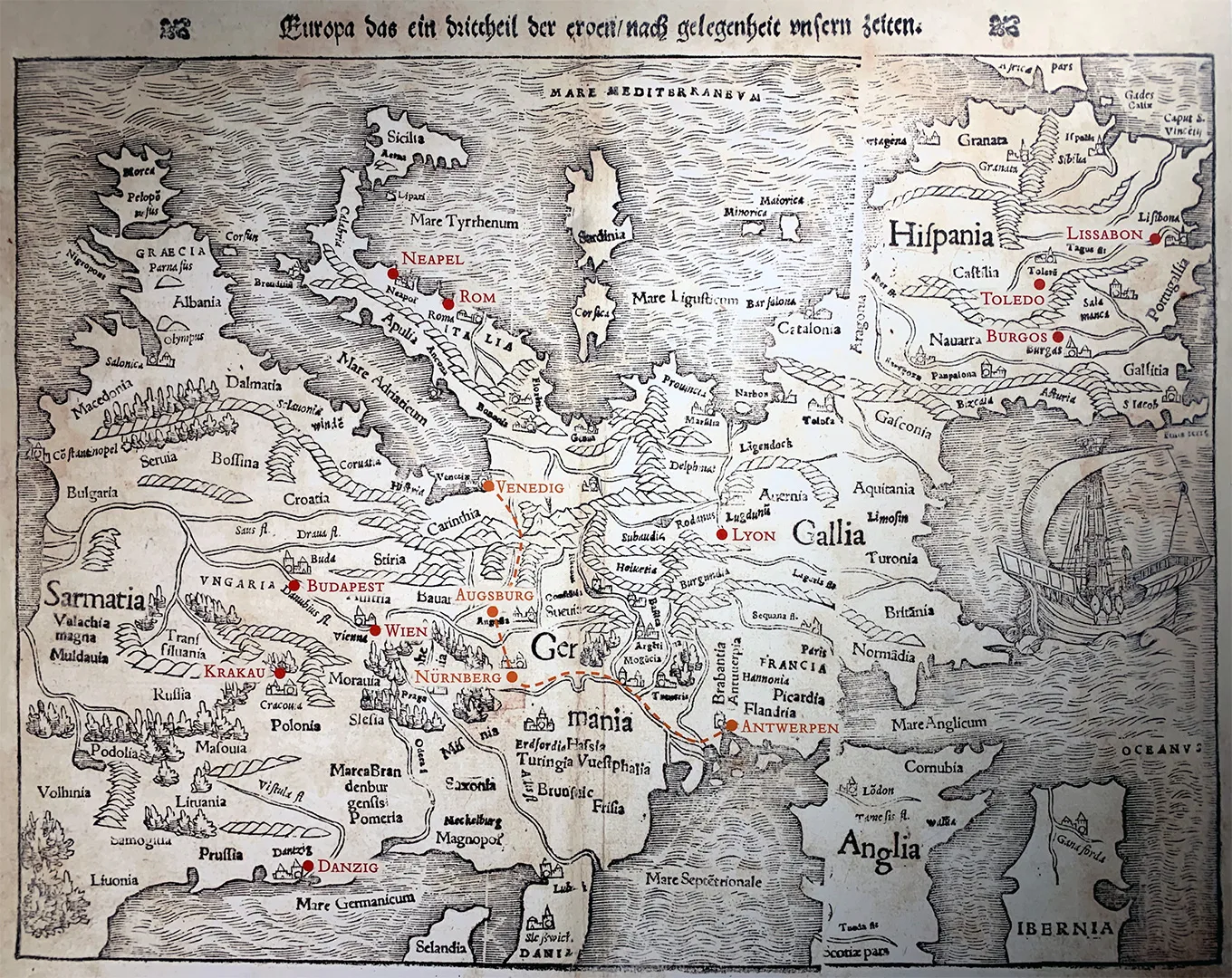

‘Europe the third part of the earth.’ In the ‘Cosmographia’ by Sebastian Münster, first published in 1544, Europe is still upside down, with the north below and the south above. But it’s still easy enough to get your bearings. Augsburg is at the centre of what was then Europe’s most important trade route by land, from Venice to Antwerp via Augsburg and Nuremberg.

Fugger and Welser Erlebnismuseum, Augsburg

Fustian links Orient and Occident

Even at the peak of their wealth, power and status, the Fuggers didn’t conceal their origins, happily acknowledging the weaver Hans Fugger from the village of Graben, four hours’ travel south of Augsburg. The family’s progenitor had taken up residence in the city in 1367. The timing was right. An exciting innovation was taking hold: fustian. Export of this new type of fabric made the area between Lake Constance, the Danube and the Lech an important industrial region within Europe.

But manufacturing the product was easier said than done. Fustian is a mixed-weave fabric. The cotton weft is added to the linen warp threads. Flax could be grown everywhere in this area, and processed into linen. The cotton that was also needed was a different story, however. In the Late Middle Ages, it came from the Mediterranean region, Syria, Egypt, Anatolia and Cyprus. It was brought to Venice, to the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, the German merchants’ warehouse on the Grand Canal. In fustian, East and West were woven together in the true sense of the word.

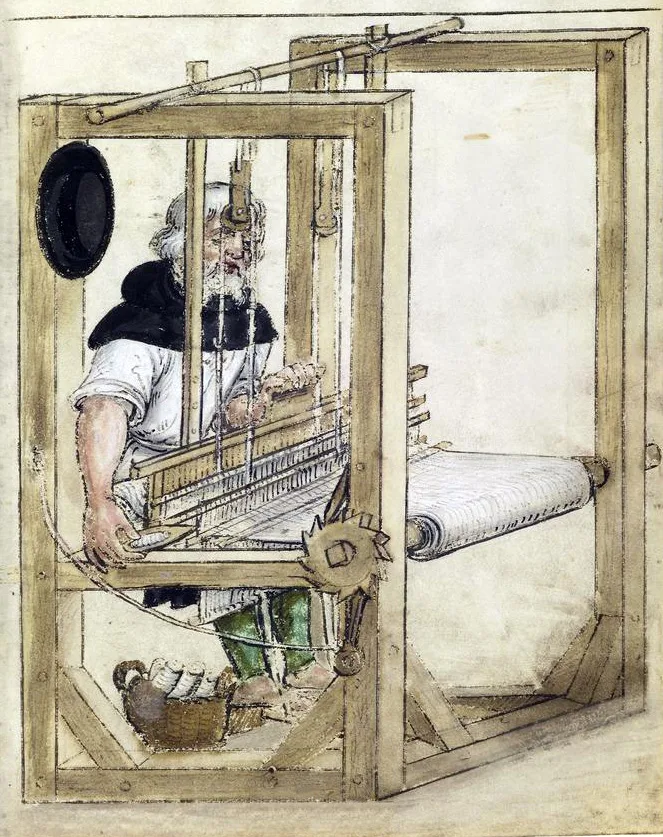

Loom with foot treadle; one part lifted the warp thread, and the other lowered it. This opened the shed for the shuttle. Fustian, a mixed fabric, was manufactured in three sorts: smooth, napped on both sides or napped on one side only. From as early as the 1370s, this leading export product was classified into standard sizes and quality classes, and seals affixed. Buyers were able to trust the certificate. Depiction from the Nuremberg House Books (Nürnberger Hausbücher), ca. 1500.

Nuremberg City Library

According to established tradition, the fabric was transported across the Alps in convoys of carts, in individual daily stages. The cargo was delivered to a warehouse known as a ‘Sust’. From around 1500, there was competition for the cart convoys. Goods manufacturers provided direct convoys. A single bale carrier was in charge, transporting the goods along the entire route in several stages.

Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto (1697-1768): Venice, Rialto Bridge and Fondaco dei Tedeschi, ca. 1750. The name of this business house, founded in the 13th century, should be understood broadly. While the southern Germans were the main contingent, the Dutch, Swiss, Austrians, Bohemians, Poles and Hungarians also operated there.

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

The textile industry was the economic lifeblood of the city and region of Augsburg. In the 15th and 16th centuries, more than a quarter of taxpayers made a living from cloth manufacture. With homeworkers often unable to pay cash for the raw materials, and sales still limited to the local market, an innovation fraught with consequences had begun to emerge as early as 1400.

Shrewd merchants recognised an opportunity. As ‘agents’, they became general enterprisers, procured and distributed the raw material, offered credit, collected the goods from the home workers, brought them to the national market – and delivered new raw materials. Around 1550, almost 300 weavers worked for the Fugger business in Weissenhorn near Ulm. Sovereignty over this area, including a small market town, had been conferred upon Jakob the Rich by Emperor Maximilian in 1507. The Fuggers eventually had fundamental and judicial rights, and rights of demesne, in more than 200 places, enabling them to withstand any crisis.

Networking

Fugger didn’t know the word. He built his own network, in the form of stone and bone. Stone – an interlinked web of permanent establishments located in all of Europe’s major centres of trade. Bone – a staff of loyal employees in each place.

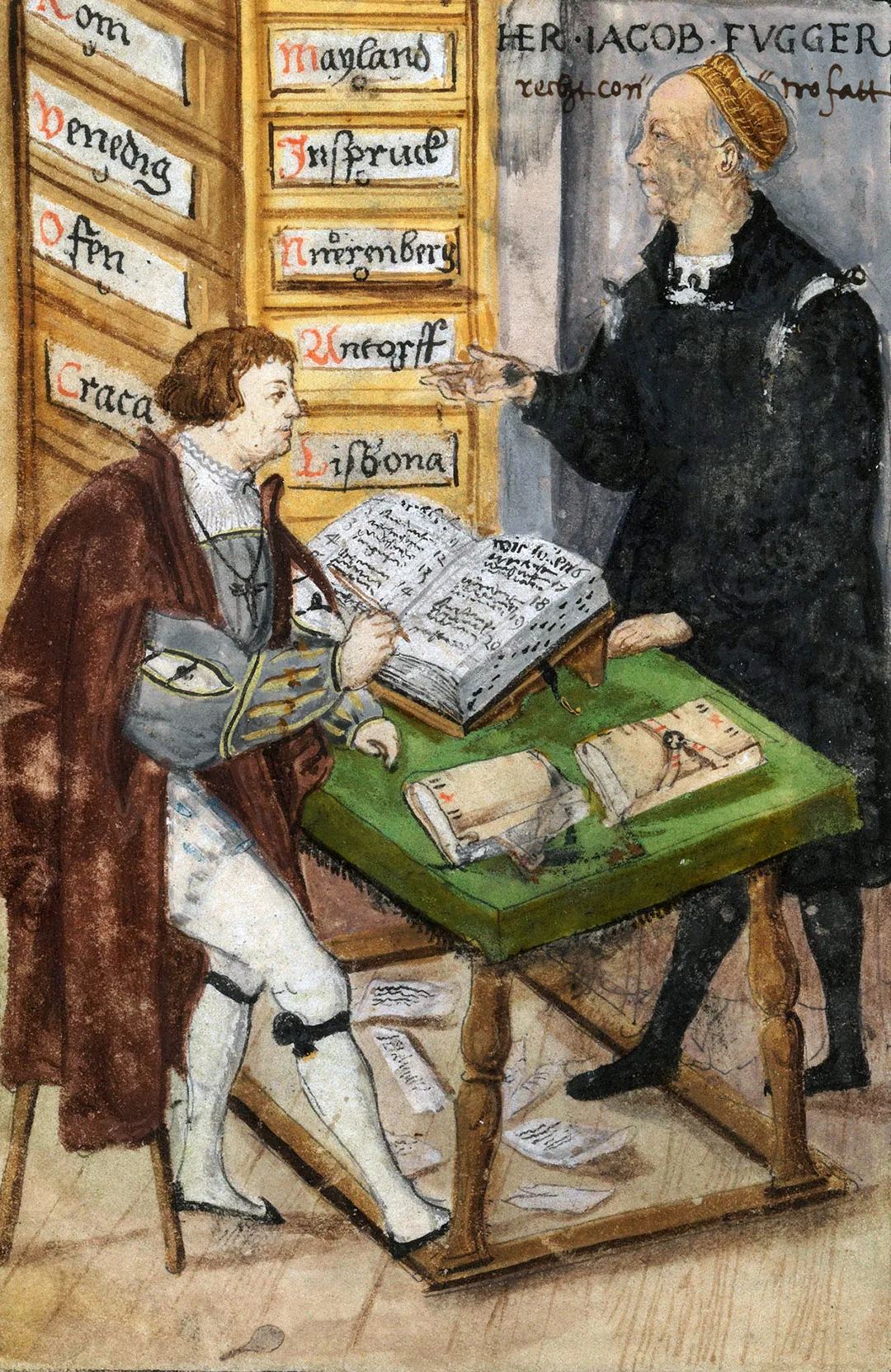

Jakob Fugger (1459-1525) and his accounts clerk, Matthäus Schwarz (1497-1574), at the Fugger headquarters on the Rindermarkt in Augsburg, ca. 1520. Nearly 50 m² in size, the ‘Goldene Schreibstube’ took its name from the gold-coloured strips of maple panelling. Painting by Narziss Renner (1502-1536), whose notation ‘recht contrefatt’ attests that the painting is a true representation.

Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig

Who’s the boss, and who’s the right-hand man? If you look at the subjects’ heights as painted, and the activities depicted, any doubt is quickly dispelled. Fugger towers almost flamboyantly above his chief accountant, dictating, while the accountant writes down what he says. But Fugger, who is wearing only a cap and a long dark doublet, still has to be identified with a special label: HER IACOB FVGGER. No such information was needed for his top man. Everyone knew who he was!

Was Matthäus Schwarz on his way to a fancy-dress ball? Not such a far-fetched idea. Schwarz had two passions: numbers, and dressing up. The first of these passions is evidenced by Fugger’s exorbitant profits, and the second by Schwarz’s nickname, ‘Kleidernarr’ (literally ‘clothes fool’). From 1520 to 1560, Schwarz had his portrait painted in full fashionable dress every year. The result was a veritable ‘Kostümbuch’ (the Schwarz Book of Clothes). A bit much worldliness in a time when people were still fixated on the afterlife. But what the heck – this pair’s business dealings were much more interesting!

Folder with files

The drawers for the documents have remained the same, but they’re opened in a slightly different order today. The top compartment of the filing cabinet: Rome. No surprise there. The Pope greeted and received Fugger as ‘his dear son’, the cardinals stood up when he entered the room, and even ‘the heathens [were] amazed by him’, meaning Fugger, not the Pope, as a contemporary chronicle reports. This was because the first Swiss Guards were recruited in 1505 with a loan from Jakob Fugger.

Venice has already been mentioned. Ofen [Budapest] and Craca [Krakau] refer to the Hungarian trade. ‘Mayland’ is the metropolis in Lombardy, ‘Jnspruck’ the hub of the Tyrolean mining industry, and ‘Nuerenberg’ a major trans-shipment centre. There remain Antorff [Antwerp] and Lisbona [Lisbon], of which it would soon be said: ‘New lands, new business dealings. Italy, the whole Mediterranean, is becoming uninteresting. The big deals come across the big oceans.’

We are owed, we owe

In the centre of the picture, at its heart, is the ledger with numerous index tabs, and next to that two smaller books. The two opposing pages are headed ‘we are owed’ and ‘we owe’. What seems self-evident today was an accomplishment at that time: double-entry bookkeeping. In Italy it had already been the practice since the ‘commercial revolution’ around 1200; north of the Alps it was used for the first time around 1520, in the Fugger trading house.

The path this innovation took to reach Augsburg is obvious. Jakob Fugger was sent to Venice as a teenager. He was soon representing his family’s firm in the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, spending a good 10 years doing so. Three decades later, Matthäus Schwarz also undertook commercial training there. Back in Augsburg, Schwarz wrote one of the first textbooks on double-entry bookkeeping, a standard work. Meanwhile, he made fun of merchants who were recording their transactions ‘in poor records’, ‘sticking notes on the wall’ or ‘keeping their accounts on the window ledge’. Tempi passati, as demonstrated by several slips of paper under the table. It’s hardly surprising that Schwarz had himself painted with his favourite book: ‘Debit and Credit’.

Collect interest, endow, have a prayer said

‘You shall not charge interest.’ In 1215 Pope Innocent III explicitly confirmed the prohibition on interest decreed in the Bible. Not Jakob Fugger’s ideal scenario. He brought in renowned theologian Johannes Eck (1494-1554) of Ingolstadt to argue his case. Eck’s task was to persuade the Church to permit interest of 5% – and he was reasonably successful: charging interest was not allowed, but it wasn’t punished either.

Fuggerei in Augsburg. In 1521, Jakob Fugger the Rich established the world's oldest social housing complex still in use. The rows of terraced houses form an attractive neighbourhood, which is accessed through an entrance similar to a city gate.

Wikimedia

Martin Luther (1483-1546), a contemporary of Jakob Fugger, complained that [commercial] ‘companies are nothing more than a conceited monopoly’. On religion too, the views of these two men were diametrically opposed. The Reformers believed in ‘faith alone’, the Catholics in ‘good works’.

In terms of donations and endowments, Fugger was more Catholic than the Pope. When he did a good deed, he did more than simply toss a worn old coin into a beggar’s hat. He donated houses, for the ‘pious poor day labourers and craftsmen’. Not two, not four, not ten. There were 67 of these houses, together with a small church and associated priest. Even today, the 140 apartments are allocated by a committee to Catholics only, and the residents are still required to pray for the salvation of the founder and all Fuggers, once a day, reciting the Lord’s Prayer, the Creed and the Hail Mary.

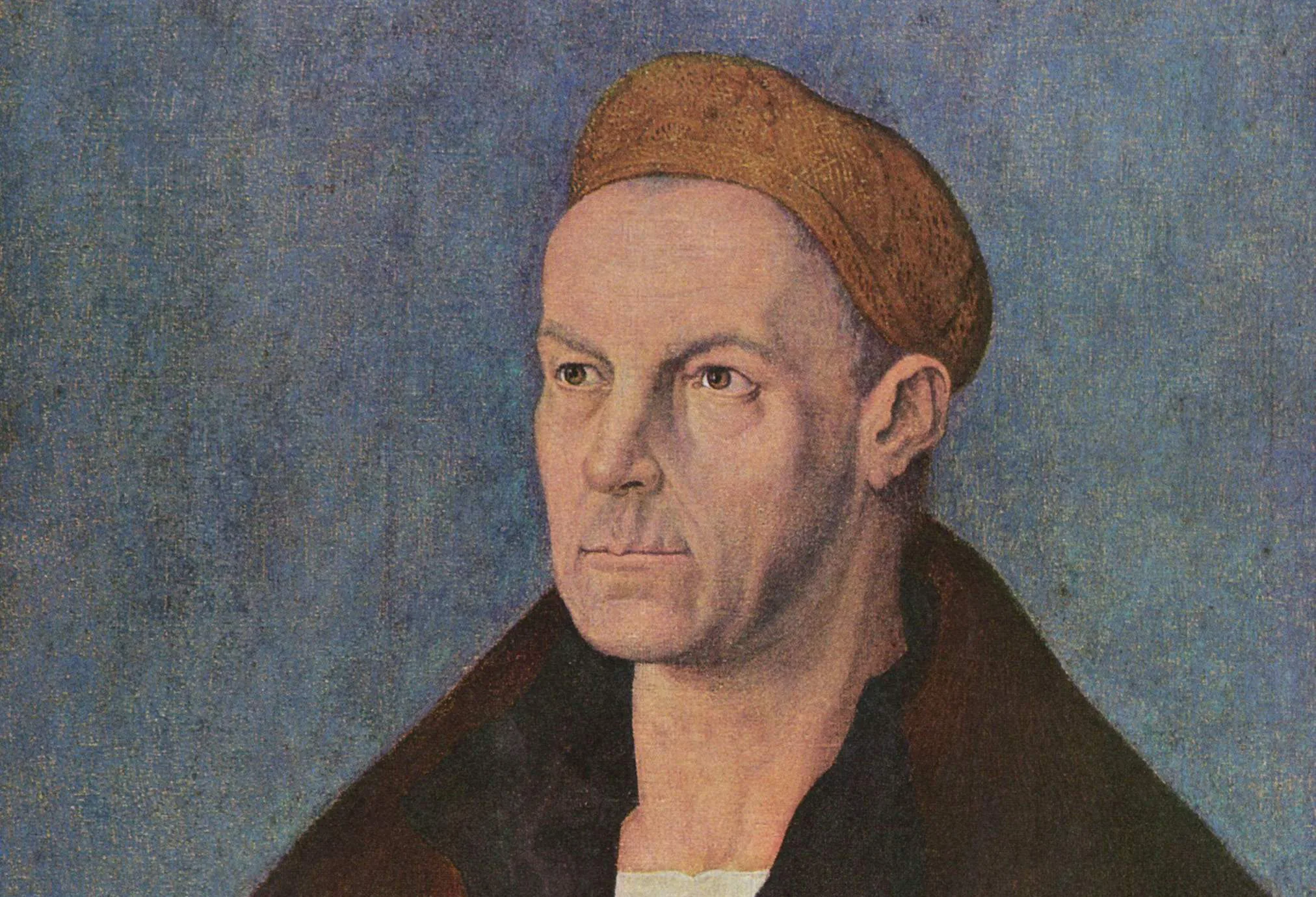

To ensure residents don’t forget to perform this intercession, when they move in they are given a portrait of Jakob Fugger, painted by none other than Albrecht Dürer. Most hang the portrait in the corridor. Since the founding of the Fuggerei the rent has been symbolic. Today it’s 88 cents, and that’s not per month – it’s per year.

If they’re in the light, we see them; in the dark, they’re out of sight

In 1500, around 30,000 people lived in Augsburg, about the same number as in Prague. Augsburg was one of the largest cities in the Holy Roman Empire, surpassed only by Cologne. Jakob Fugger and Matthäus Schwarz were two among 30,000 people. The most important?

There was only peripheral mention of the hundreds of weavers who worked for the House of Fugger. The miners in the Tyrol were not mentioned, nor were their colleagues and families in the mines in Hungary. How unfair can history be? A look into the past is never the end; it’s only ever the beginning.