Swiss National Museum

Unus pro omnibus, omnes pro uno

The political slogan ‘One for all. All for one’ has gained new relevance during the coronavirus crisis. The maxim came into widespread use in Switzerland in connection with coping with natural disasters in the 19th century, but it has its roots in the early 16th century.

When even the notoriously anti-government weekly WOZ prefaces its commentary on the Federal Council’s anti-coronavirus measures with ‘Unus pro omnibus, omnes pro uno’, this pro-state motto must chime neatly with Switzerland’s attitude to managing the current crisis. But where does this motto come from?

Politicians have good reason to believe they can use the motto to evoke a sense of solidarity among the Swiss people. The motto ‘One for all. All for one’ is firmly engrained in the country’s collective memory. It’s probably the Federal Council itself that has brought it back into current circulation. As the coronavirus crisis escalated, Alain Berset used the phrase repeatedly when calling on the Swiss people to show solidarity: Stay at home! Protect the most vulnerable among us, and by doing so save our community from disaster.

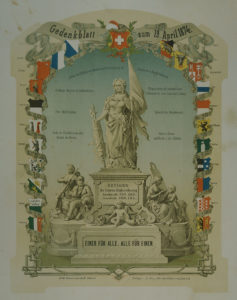

‘One for all. All for one’ found its way into the national self-image after the foundation of the modern federal state in 1848. The phrase became the motto of an elaborate presentation of the revised constitution of 1874. In 1889, embodied in Konrad Grob’s painting ‘Winkelried at the Battle of Sempach’ it entered the old Council of States chamber in the Bundeshaus West, the Swiss Parliament Building. And since 1902, the Latin version has hovered above the heads of our federal politicians in the dome of the Bundestag building, as an unofficial national motto.

Memorial sheet to mark the revision of the Swiss Federal Constitution, 1874.

Swiss National Museum

In the second half of the 19th century, the fledgling state used this maxim to appeal to the sense of national unity. Each individual canton had to make certain that it served everyone’s interests to hand over sovereignty to the Federal state. And in particular, the conservative Catholic groups which had opposed the founding of the Federal nation had first to be won over by the liberal state.

On this political basis, the motto then also displayed its solidly uniting effect in the event of disaster, as climate historian Christian Pfister has shown. Following the devastating Glarus fire in 1861, a nationwide fund-raising campaign collected an enormous sum of money. This not only provided vital material aid, but also created a feeling of community. In line with the motto: ‘All the cantons of Switzerland for one Swiss canton’, or simply ‘the whole Swiss nation for the destitute people of Glarus’, a mark of national solidarity and duty was signalled.

The motto hovers over the heads of the nation’s policy-makers in the Bundestag building.

Wikimedia / Swiss Parliament

WINKELRIED STARTED IT ALL

Although the motto only became popular in the course of the 19th century, it had come into being much earlier. It escalated in the memorial culture surrounding the dying ‘Winkelried’. In 1386, the hero from Nidwalden near Sempach is said to have turned the tide of the hopeless battle in the Old Swiss Confederacy’s favour with his self-sacrificing death. By throwing himself onto the enemy’s pikes, he created a breach for the Swiss soldiers with the words: ‘I shall make a passage for you’. As he died, he pleaded with his comrades: ‘Look after my wife and children’. The heroic victim gave his life for the good of his community: the Swiss Confederation. Conversely, he was able to expect this same community to take care of the loved ones he left behind: ‘One for all. All for one’.

Tellingly, this hero of Sempach only appears in the official culture of commemoration around 100 years after the battle. Another 50 years after that, in 1551, he was then given the name ‘Winkelriet’ in Hans Rudolf Manuel’s depiction of the battle. He subsequently assumed the role of heroic victim in the regular commemorations of confederate battles, and thus became engrained in the nation’s collective memory. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the figure also underwent some customisation. During the Enlightenment Arnold von Winkelried was venerated as a patriotic citizen soldier. In 1723, he got his first monument, as a sculpture on a fountain in Stans. Around 1750 the famous Zurich painter Johann Heinrich Füssli did a portrait of this Arnold von Winkelried, who historically had never in fact existed.

Winkelried monument in Stans.

Swiss National Museum

Into the second half of the 20th century, Winkelried remained a well-known figure primarily due to two works: firstly, Zurich historical painter Ludwig Vogel’s oil painting ‘Die Eidgenossen bei der Leiche Winkelrieds’ (The confederates with Winkelried’s corpse) dating from 1841, and secondly, the Winkelried monument created by Ferdinand Schlöth and formally unveiled in Stans in 1865. Until the 1970s, Swiss schoolchildren had the Winkelried message drummed into them through school murals, textbooks and children’s literature. So today, it’s mainly Swiss people aged over 65, those who are particularly at risk from the coronavirus crisis, with whom the Federal Council’s appeal: ‘One for all. All for one’ is most likely to strike a chord.