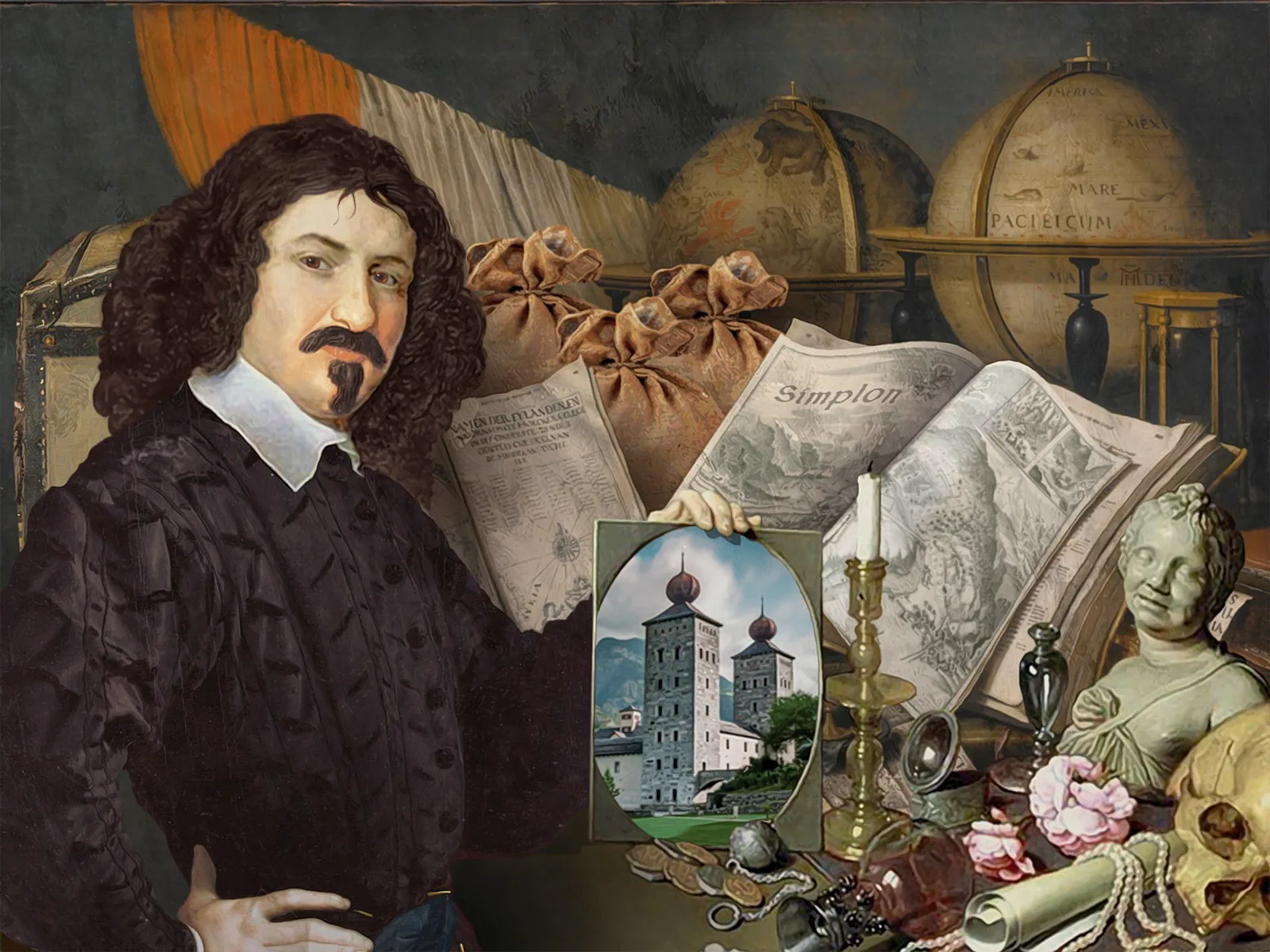

The geopolitician from Brig

In the middle of the Thirty Years’ War, Kaspar Stockalper made the Simplon pass into a major European transport artery. A man of immeasurable wealth, he was Switzerland’s first serial entrepreneur. Stockalper mixed with emperors, kings and popes. He was also involved in European politics – until it all fell apart.

Exploiting the geostrategic situation

Combining business with politics

The King of Brig

In a three-part series, historian and author Helmut Stalder charts the rise and fall of Kaspar Stockalper, the “King of Brig”:

Part 1: The geopolitician from Brig

Part 2: Neutrality as a business model

Part 3: Making money till the end