Library of Congress

Sharing is caring

Letting agents, vehicle suppliers, financial services providers: over the past few decades, a colourful profusion of products and services has assembled under the banner of the ‘shareconomy’. Its history runs deep, and has some murky secrets.

The sharing economy was the hot new thing. Sharing instead of owning: about 10 years ago, this formula promised efficiency gains and the best returns. Since then our love affair with Airbnb, Uber, Kickstarter and the like has cooled somewhat. Precarious terms of employment, accounting tricks and a lack of social responsibility have scratched the shiny image of the sharing economy – the shareconomy, for short. High time, then, to take a look at its history. It tells us a lot about the opportunities and risks of sharing.

Out of the crisis

The shareconomy made its grand entrance just at the moment when the international financial world collapsed. In 2008 the real-estate bubble burst. Starting in the USA, the global banking industry’s grand promises of spectacular profits and fantastical returns on investments dissolved in a chaos of smoke and mirrors. Drowning in its wake was a legion of insolvent small savers. But while the world gaped in bewilderment and shock at the behaviour of the investment banks, the professionals were already setting sail for new safe harbours to invest their venture capital. These were well hidden in altruistic waters. Of all things, sharing – the good old act of charity – was to become the next money-making scheme. Huge online platforms enabled people to provide private possessions such as homes, cars or cash to total strangers. The ingenious twist in this was that for each transaction, the platforms pocketed a few per cent in fees. For the individual, that was acceptable. In total, however, it brought a respectable profit. Communicating the idea was also easy. Thanks to social media, the sharing of private content and data had been big business for years already. Sharing is caring has taken on a new meaning in the 21st century.

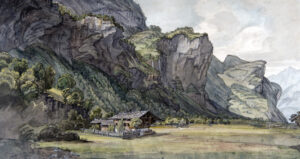

Common land in Meiringen, 1817. Watercolour drawing by Ludwig Georg Vogel (1788-1879).

Swiss National Museum

From the field to the ledger

Sharing has been an essential aspect of our economy for centuries. Village communities were already managing specific forest and field areas on a collective basis in the High Middle Ages. These shared commons were of fundamental importance for agriculture. When the Republic (from the Latin res publica, ‘public affair’) matured into an attractive constitutional alternative in the early modern period, the status of sharing also changed. The broader the group that had a say in political decision-making, the more important it became for knowledge to be shared. In order to produce enlightened and informed male citizens – it wasn’t until 1971 that female citizens followed at federal level – educational institutions became vitally important. Along with the expansion of compulsory school attendance, in the late 19th century the founding of the National Museum and the National Library were also indebted to these ideas of republicanism. If the latter still carries out its mission of collecting together all publications about Switzerland and making them accessible to the general public, then it is fundamentally in the service of the Republic.

The tragedy of sharing

But sharing knowledge also has drawbacks. Patent law, for example, is there precisely to prevent the free circulation of knowledge, to safeguard innovations. As it happens, the problems of sharing became more apparent in the second half of the 20th century. Under the banner of the tragedy of the commons neo-conservative theoreticians branded the collective management of goods and services inefficient. With the argument that they are minimising damage to property, society and the environment, these groups have been pursuing the privatisation of postal services and railways, among other things, since the 1980s. This economic scepticism about sharing wasn’t overcome until, firstly, the internet became part of everyday life and, secondly, the financial world was rocked by the crisis of 2008. It was only in the maelstrom of the drive for globalisation and digitalisation unleashed by the World Wide Web that sharing and economy came together again. The idea of republicanism fell by the wayside. Perhaps the much-criticised shareconomy would do well to remember it.

Symbol of the financial crisis: house with boarded-up windows in the USA, May 2008.

Peter Püntener / Swiss National Museum

To mark its 125th anniversary, from 11 March to 30 November 2020 the Swiss National Library in Bern will be showing the exhibition Sharing. About libraries and sharing. The exhibition offers a glimpse behind the scenes of the National Library. It poses the question: how do we want to share knowledge today?

Sharing – A library exhibition about sharing

Swiss National Library