Between the ocean and the Alps

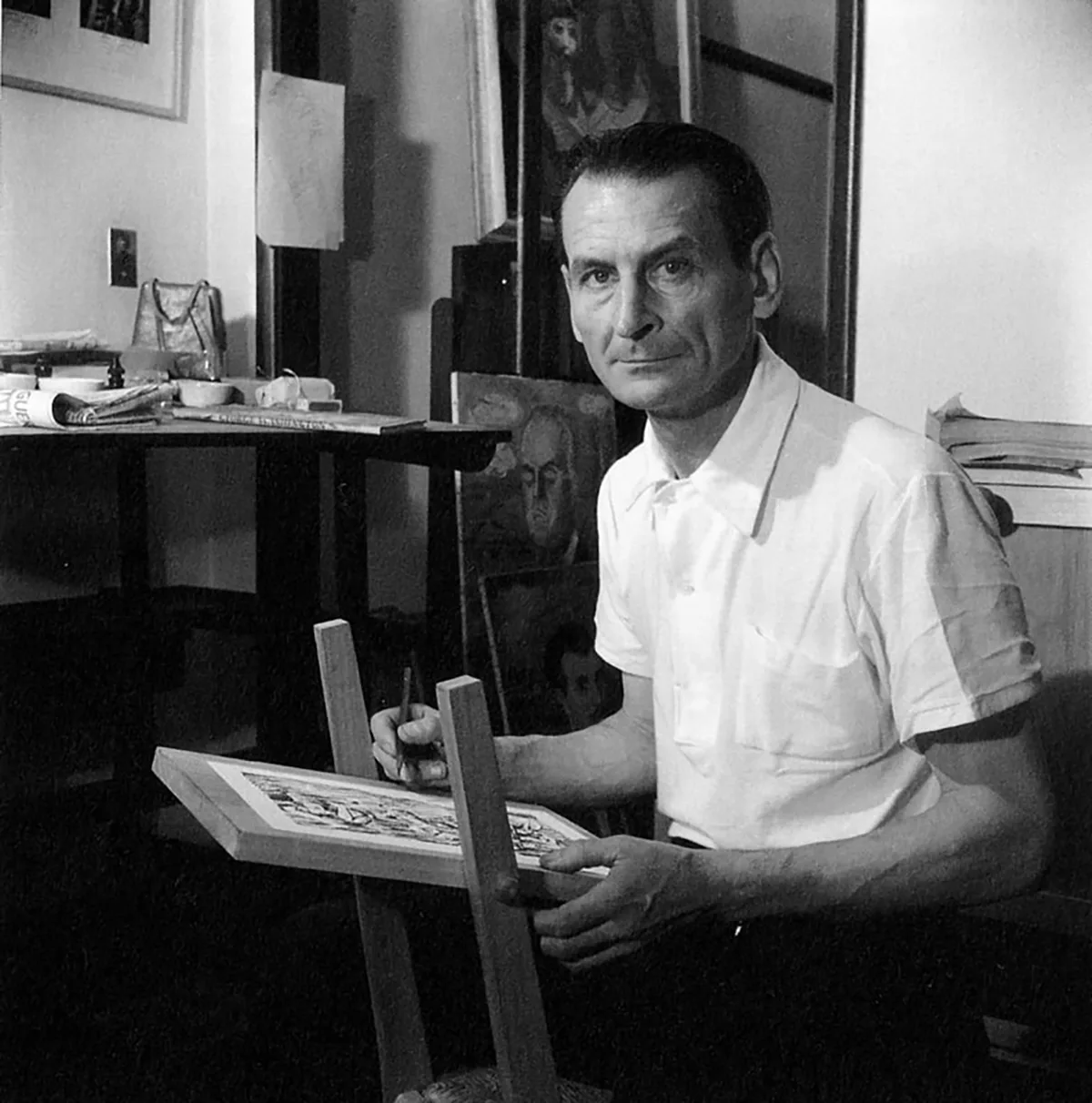

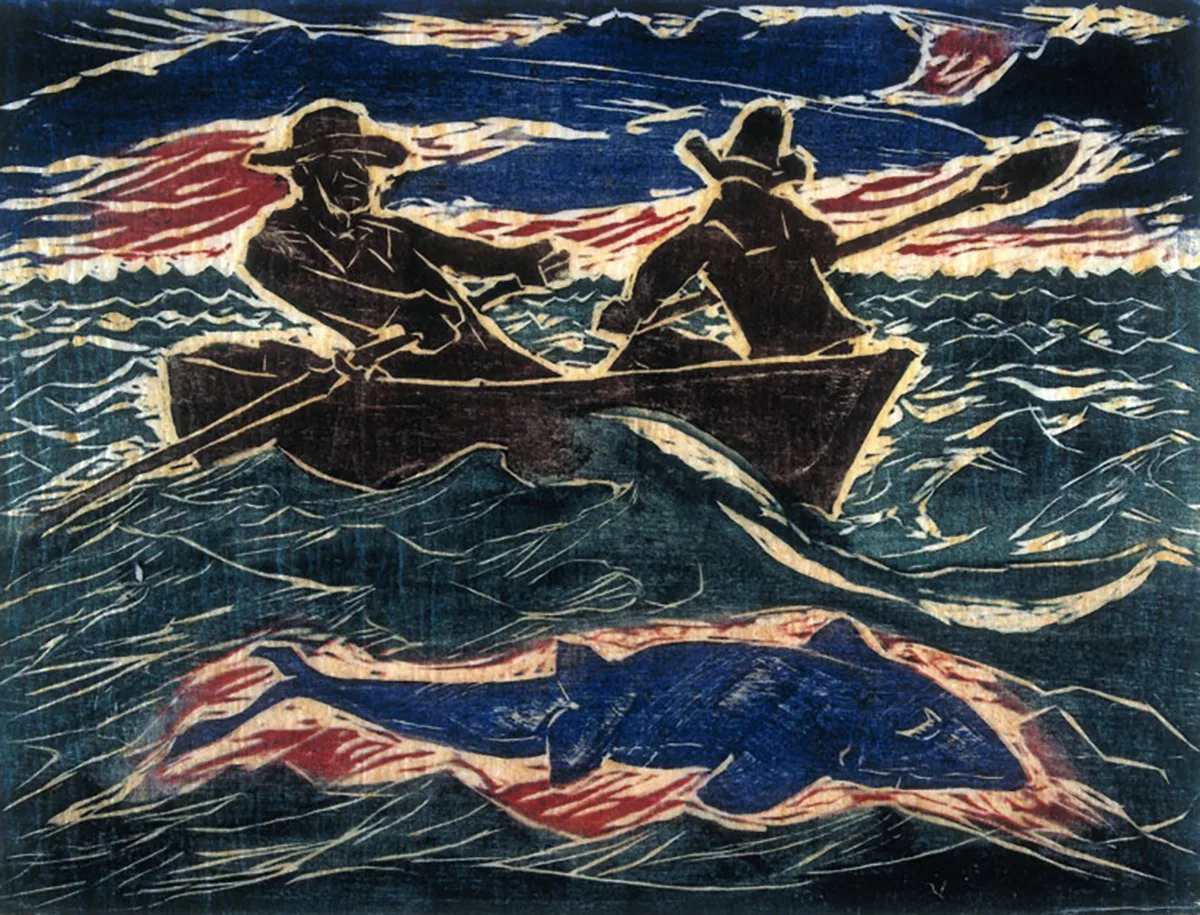

In Brazil, illustrator and graphic artist Oswaldo Goeldi is considered a master of the art of expressionist xylography – the art of engraving on wood. In Switzerland, the work of this Swiss-Brazilian dual national is yet to be discovered.

Father was a pioneer in Amazon research

Between two worlds

Unconventional – in life and in art