The museum, a global model of success

Due to the new lockdown of the museums, Hibou Pèlerin has been forced to take a compulsory break. He is using this time to read some new publications on cultural history. A brand new world history of the museum by Krzysztof Pomian has him riveted.

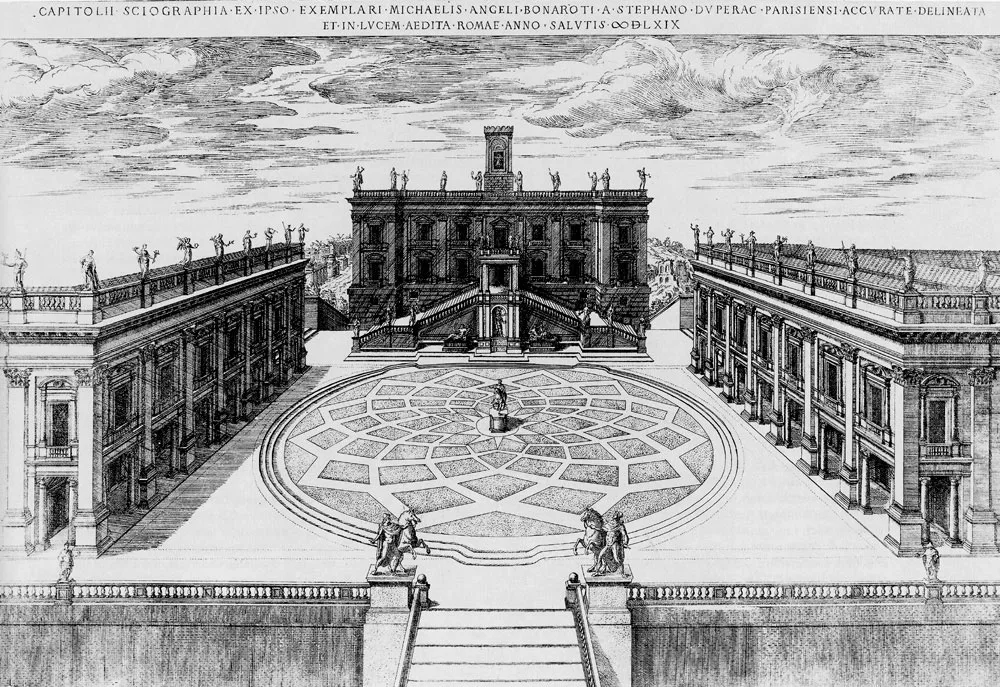

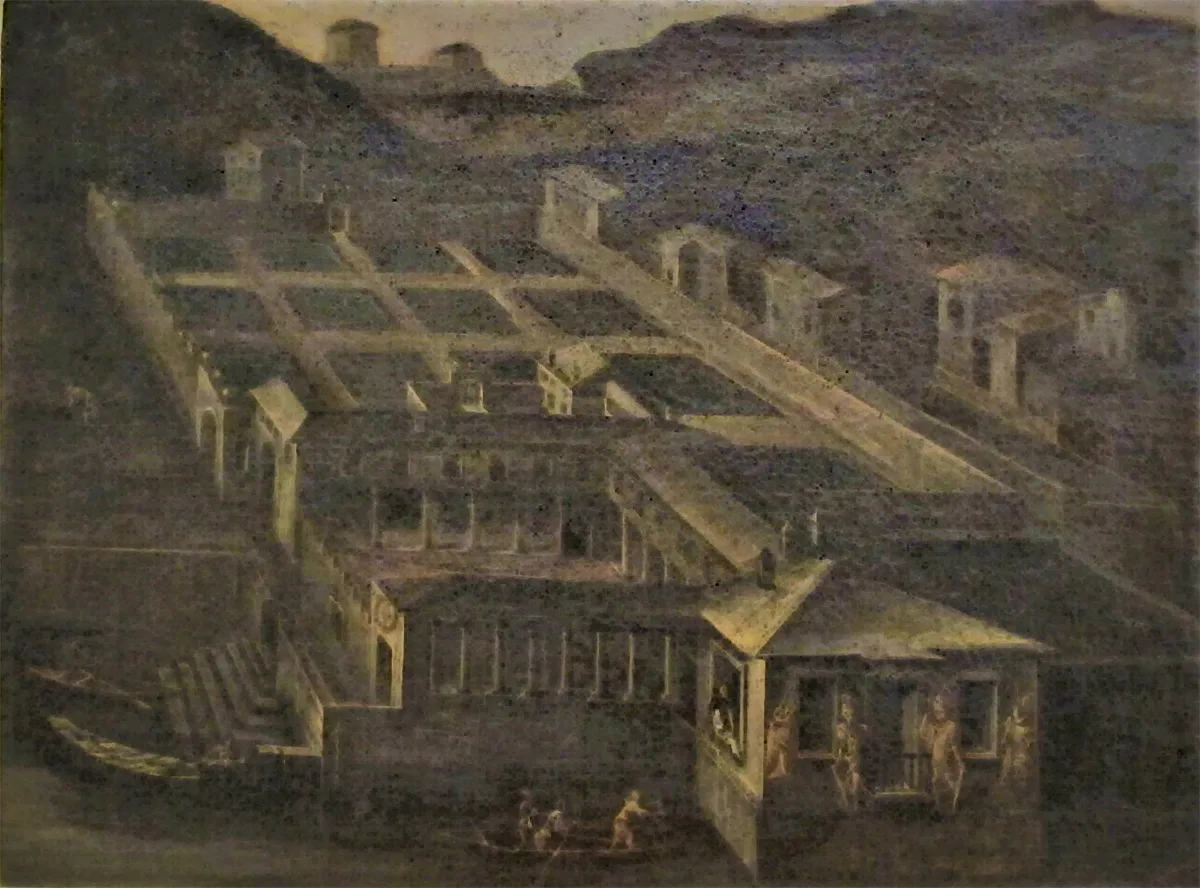

Roots in Renaissance Rome

The magnetism of the museum

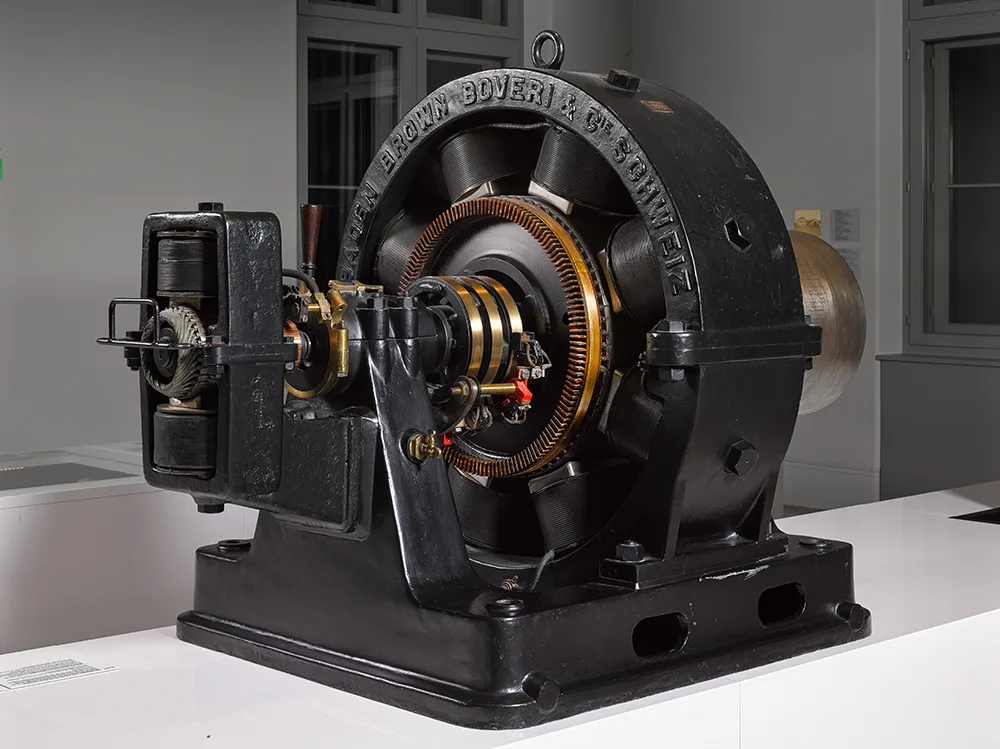

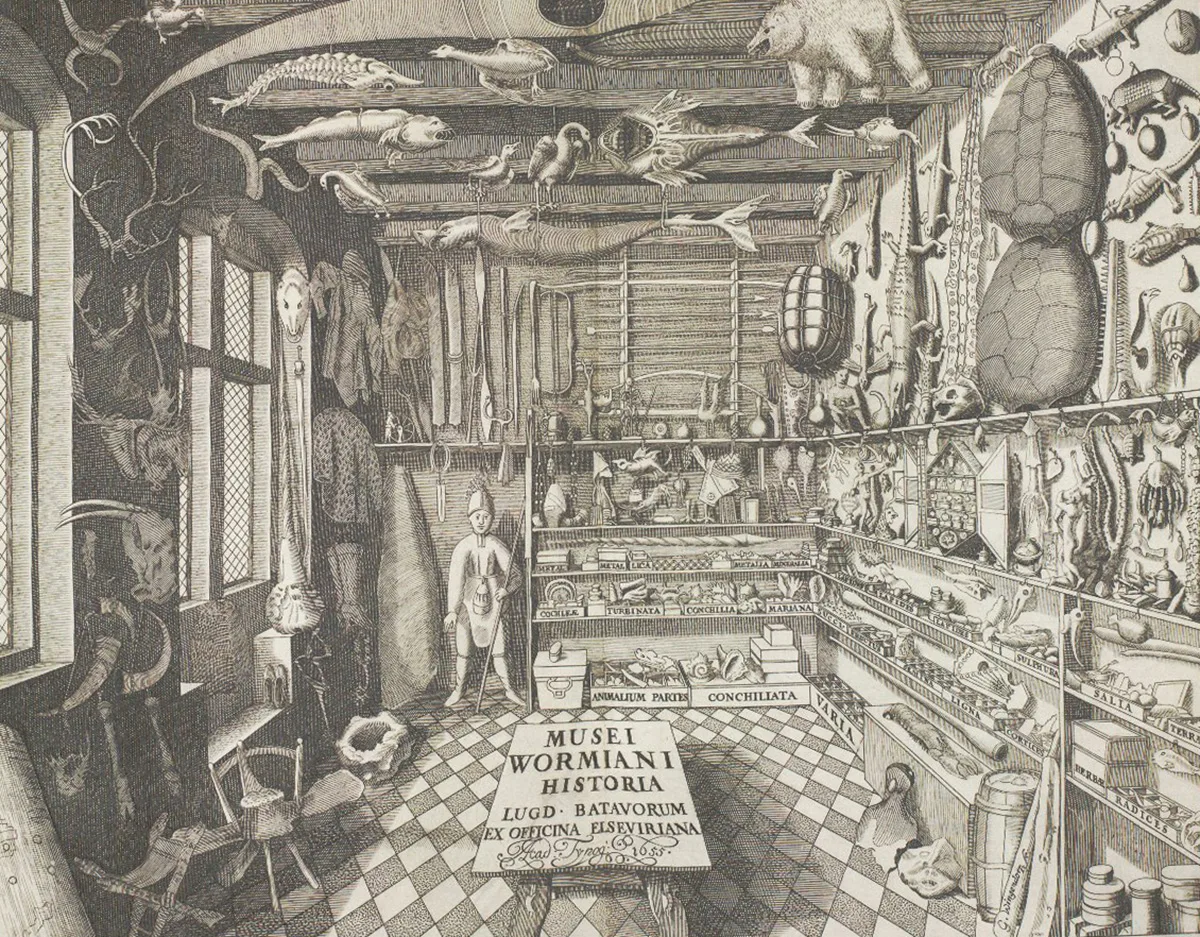

From the treasure chamber to the museum

The museum – opening the doors to past and future

Place of emotions and discourses

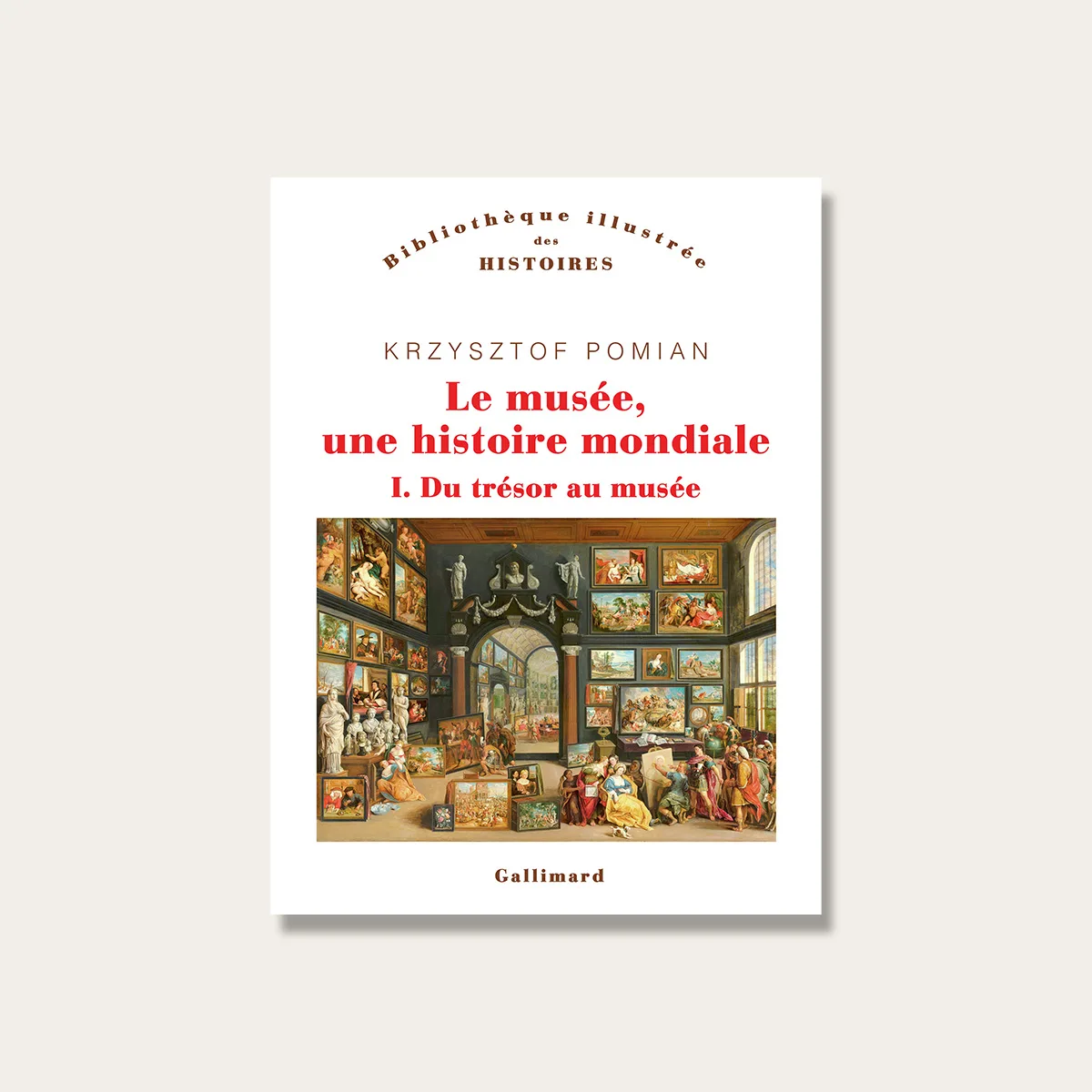

Krzysztof Pomian, Le Musée, une histoire mondiale – Vol. 1: Du trésor au musée

687 pages, abundantly illustrated, Gallimard, Paris 2020.

The work has so far only been published in French.

Interview with Krzysztof Pomian on his new work (in french). YouTube