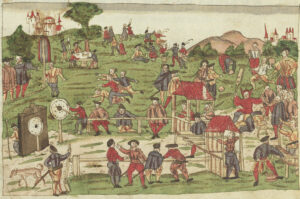

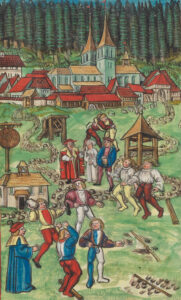

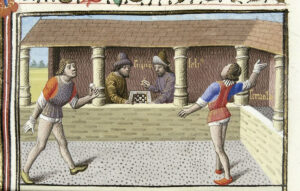

Sport in the Middle Ages

The word sport conjures up images of modern sporting pursuits, such as football, cycling, rugby and skiing. But what about during the fondly remembered Middle Ages? Did sport exist back then and, if so, how did it compare to the modern competitions held on the territory now known as Switzerland?

coveted. cared for. martyred. Bodies in the Middle Ages

There were conflicting perspectives of the human body during the Middle Ages: it was glorified, suppressed, cared for and chastised. The exhibition features many loaned exhibits from within and outside Switzerland to explore how the human body was viewed during the Middle Ages from a cultural history perspective, thereby also raising some questions about how we perceive the human body today.

Swiss Sports History

This text was produced in collaboration with Swiss Sports History, the portal for the history of sports in Switzerland. The portal focuses on education in schools and information for the media, researchers and the general public. Find out more at sportshistory.ch