Men under heavy bombardment

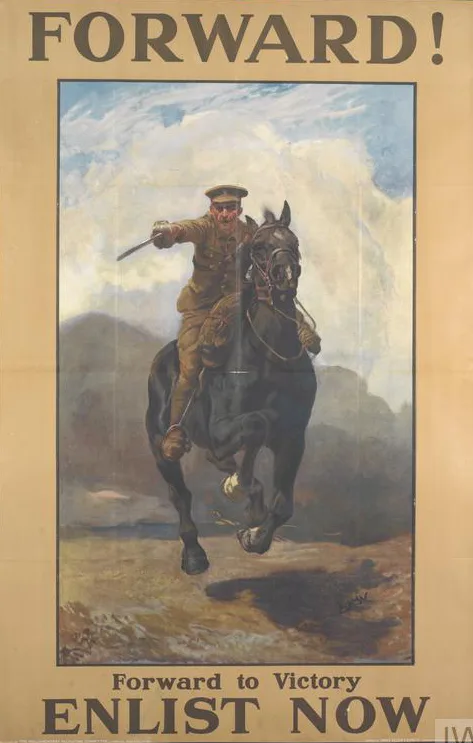

In 1914, men marched off in a rush of euphoria to join the fighting in World War I. They were following an ideal of masculinity that would be torn to pieces in a blaze of automatic gunfire. The ideal of the glorious knight turned out to be a cruel mirage.