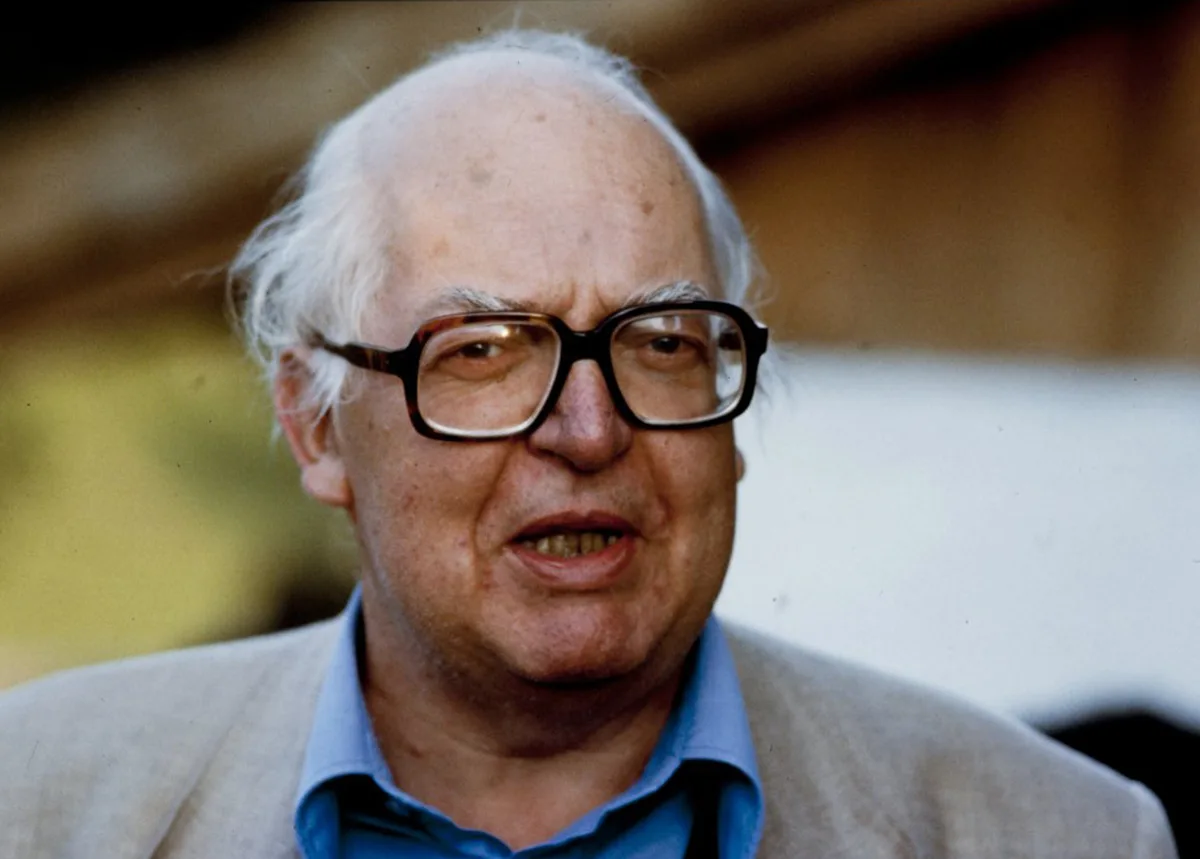

Poet-president in a snowstorm

When Václav Havel made a state visit to Switzerland in 1990, it was a minor sensation. Diplomatic documents shed light on the event from a variety of perspectives.

An unconventional president

Request for help from the West

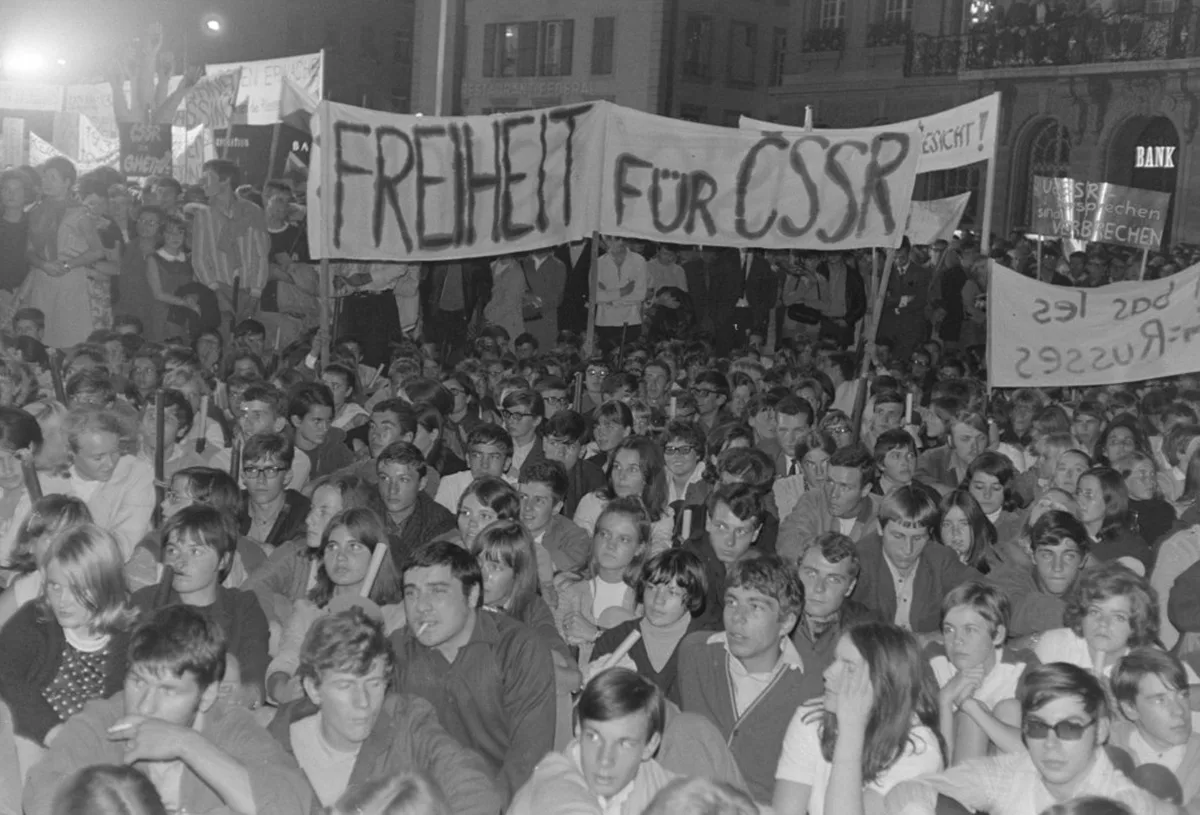

Remembering the Prague Spring

Joint research

This text is the product of a collaboration between the Swiss National Museum (SNM) and the Forschungsstelle Diplomatische Dokumente der Schweiz (Dodis), the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland research centre. The SNM is researching images relating to Switzerland’s foreign policy in the archives of the agency Actualités Suisses Lausanne (ASL), and Dodis puts these photographs in context using the official source material. The files for 1990 will be made public on the Dodis online database in January 2021. The documents cited in the text are already available online: dodis.ch/C1910. Documents relating to Havel’s visit to Switzerland produced by Czechoslovakian diplomatic circles, which the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic has made available to Dodis, can also be found at this link.