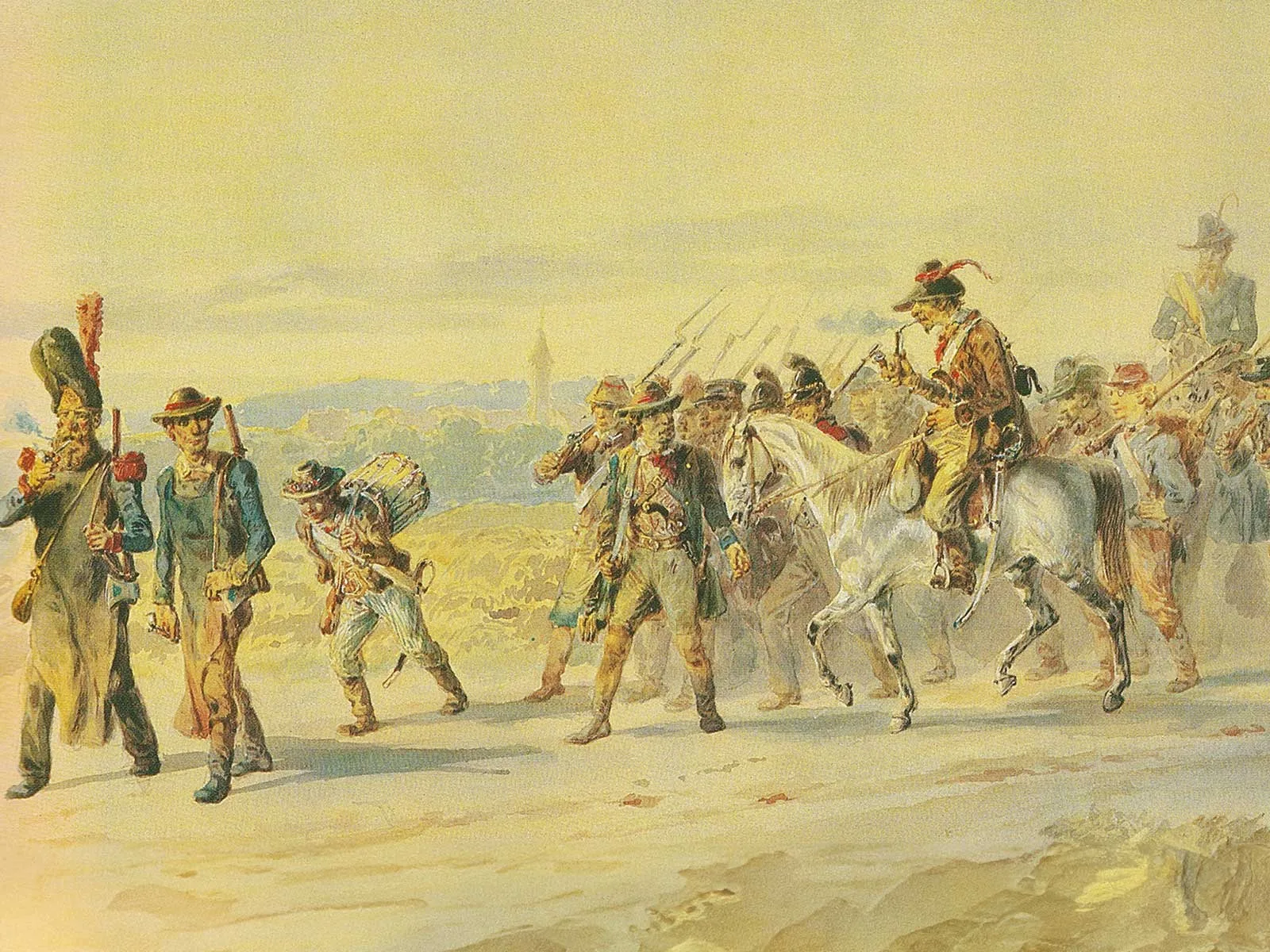

When Baden’s revolutionaries retreated to Switzerland

1849 saw the collapse of a revolution in the Grand Duchy of Baden. Skirmishes close to the border caused unease in Switzerland and ultimately triggered a wave of refugees.

Would Switzerland enter the war?

Around 10,000 refugees

How did Switzerland react?

What happened to the revolutionaries?

What remains?