The search for utopia

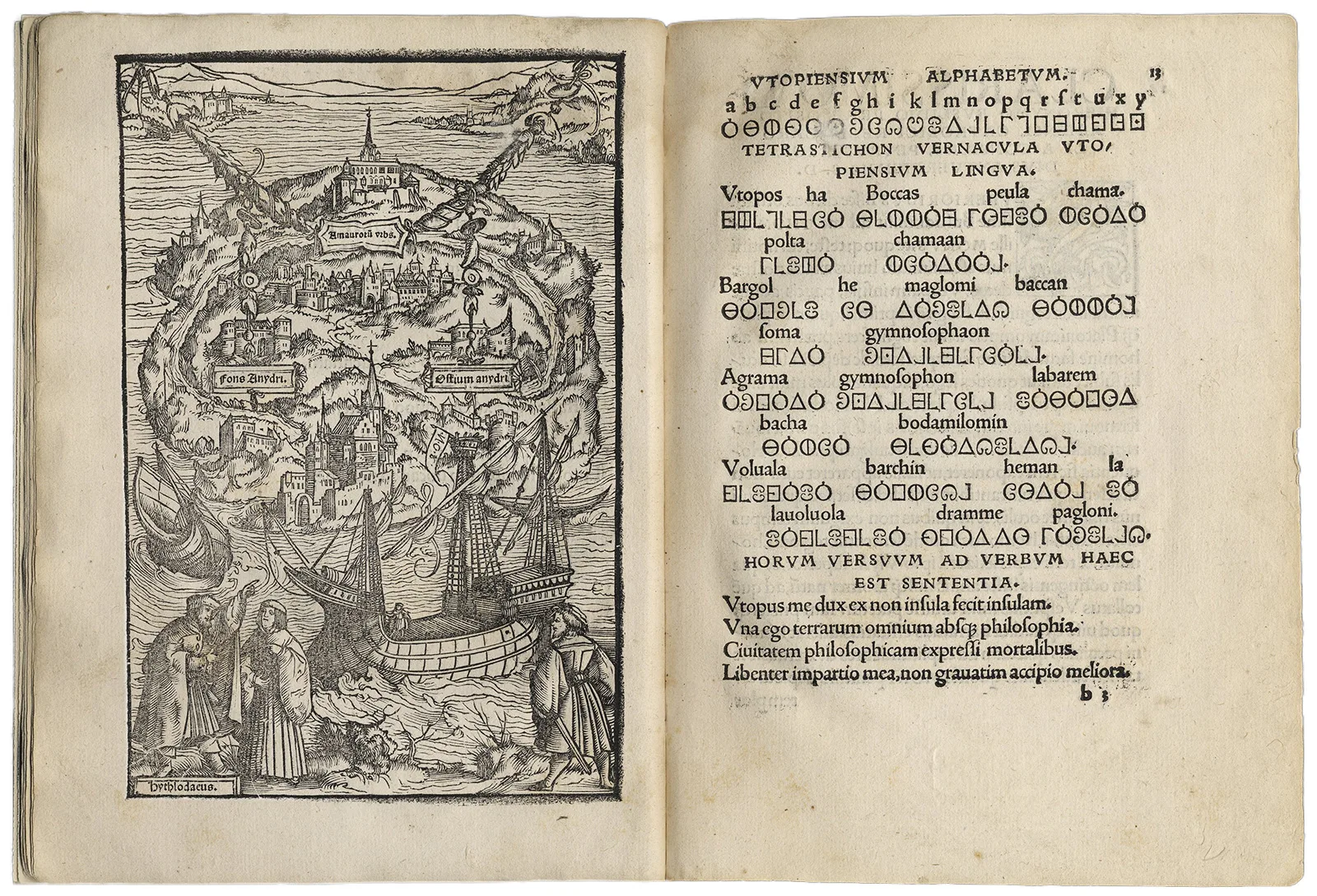

The search for utopia and the ideal society, a fairer world and a happy life is as old as humankind itself. Every era produces its own utopias; the concept, created by Thomas More, dates from 1516.

Trailer for the movie "1984" from 1984 by Michael Radford. YouTube

A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realisation of Utopias.