The nation’s sausage

The history of Switzerland comes with a big slice of ‘Wurst’. National dish or globalised cervelat: Swiss identity is all tied up with a very special sausage.

‘The worker’s steak’ for everyone

Making a cervelat in the butcher’s shop, 1985 (in German). SRF

The Landjäger too

Alternatives for the future

Meat – An exhibition on the Inner Life

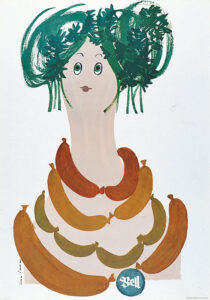

In the exhibition ‘Meat – An exhibition on the Inner Life’, the National Library takes the current discussion about meat-based, vegetarian and vegan nutrition as an opportunity to explore historical, literary and artistic perspectives on this special substance.

For a look at the exhibition, visit the website www.nationalbibliothek.ch.