Voices of Holocaust survivors in Switzerland

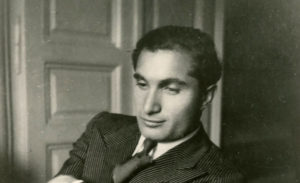

Fishel Rabinowicz (*1924) is one of the last living eye-witnesses of the Holocaust. Switzerland’s acceptance and assimilation of him and other Holocaust survivors was by no means a certainty.

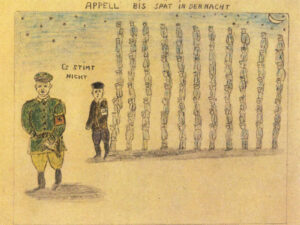

After the war, children and adolescents from the Buchenwald concentration camp, where Fishel Rabinowicz was also imprisoned, were brought to Switzerland to recover. Some of them plucked up the courage to draw pictures recalling the horror of day-to-day life in the camps. These drawings are by Kalman Landau. Archives of Contemporary History, ETH Zurich, Biographies Topics / 78

Video conversation with Fishel Rabinowicz, recorded by Eric Berkraut on behalf of the Gamaraal Foundation, short version, 2017. © Gamaraal Foundation

History of Switzerland

In the permanent exhibition on Swiss history, the National Museum Zurich presents four video conversations with Swiss people who survived the Holocaust.