Swiss National Museum / ASL

The Schwarzenbach Initiative

It was probably one of the most controversial votes in 20th-century Swiss history: James Schwarzenbach's ‘excessive immigration’ initiative of 7 June 1970.

The proposal it put forward was radical. It demanded that the proportion of foreigners in the Swiss population should not exceed 10%. Had it been accepted, 350,000 workers would have had to pack their bags and go home. The initiative had been launched by the National Action party, founded in 1961. The mastermind behind it was Zurich National Councillor James Schwarzenbach.

The referendum went to the ballot box on 7 June 1970, with a record turnout of almost 75%. It was rejected with 54% of the vote against. However, 46% of those eligible to vote – at that time still exclusively men – supported the initiative. Nobody had expected such an outcome: the proposal had been rejected by all parties, employers' organisations, trade unions and churches. Nevertheless, many people were in favour of the initiative, including workers who had close links to the Social Democratic Party and the trade unions. They were afraid that foreigners might take work away from them. During the referendum campaign, there was a lot of heated debate; the sponsors of the proposal claimed that Swiss values were in danger. The initiative, launched in 1968, caused fear and terror among guest workers at the time. In his book Cacciateli (Throw them out), the Italian journalist Concetto Vecchio describes how this atmosphere affected his parents, who used to scold their children into good behaviour with the words, ‘Otherwise Schwarzenbach will come for you’.

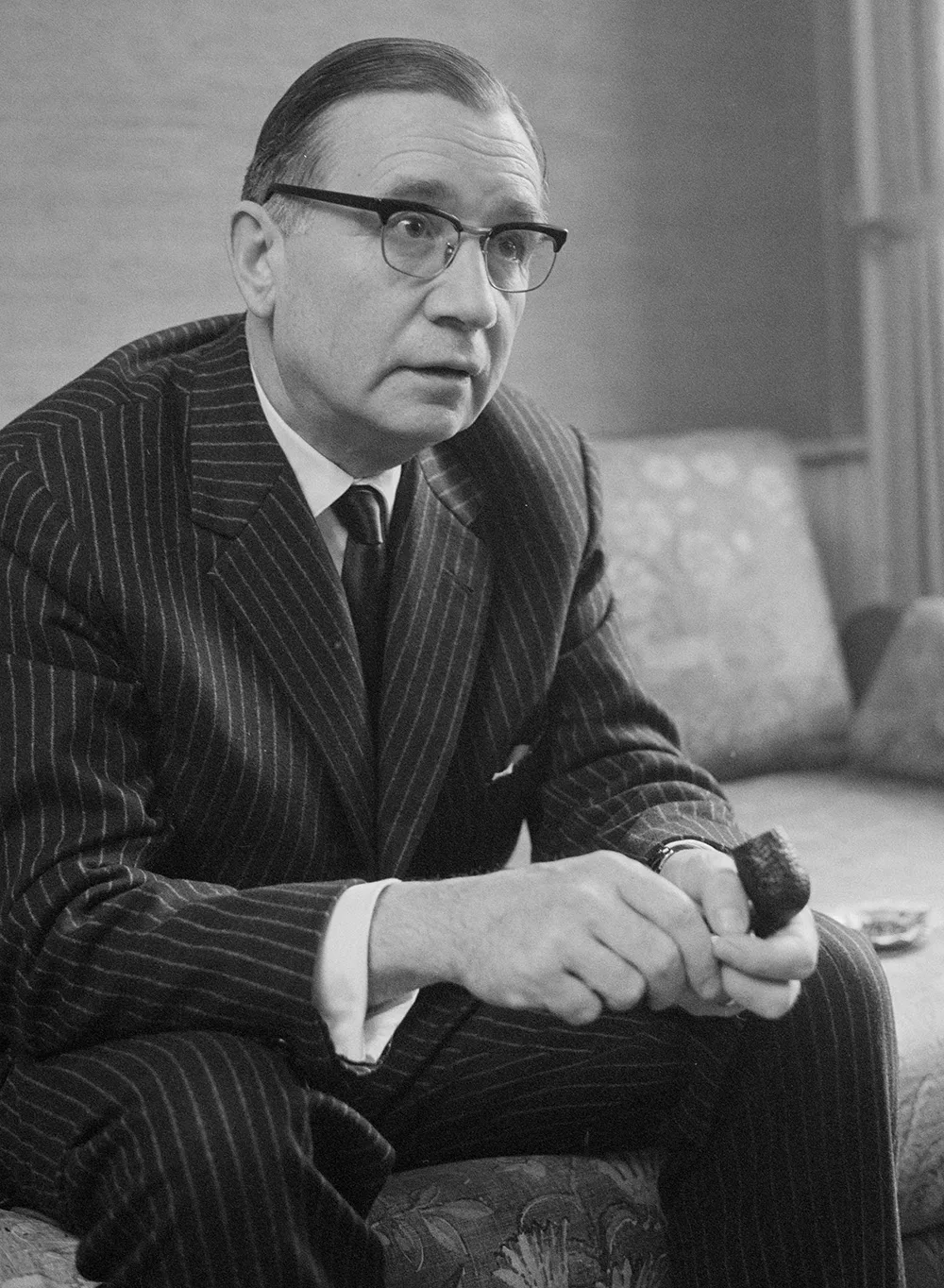

NATIONALIST, CATHOLIC, PUBLISHER

The person behind the initiative was the Zurich politician James Schwarzenbach (1911-1994). He came from an industrialist family in Zurich and was the cousin of the writer and artist Annemarie Schwarzenbach (1908-1942). He studied history in Zurich and Freiburg in the 1930s and was a member of the Nazi National Front. Schwarzenbach converted to Catholicism at an early age and took over the Catholic publishing house Thomas-Verlag after the Second World War. From 1967 to 1979 he sat on the National Council, representing first the National Action party and later the Republican Movement he founded, which disappeared from power again as early as the late 1970s. Schwarzenbach was described by his contemporaries as a loner, who was clever and rhetorically gifted, but who also made a very aristocratic and aloof impression. The Schwarzenbach family also features in the historical novel Stürmische Jahre: Die Manns, die Riesers, die Schwarzenbachs (Stormy Years: The Manns, the Riesers, the Schwarzenbachs) by the Swiss writer Eveline Hasler, published in 2015.

Although the 1970 poll was the first vote on the issue of ‘excessive immigration’, there had already been a similar initiative in 1968, which was, however, withdrawn. Even though Schwarzenbach’s proposal was voted down in 1970, the issue has never been absent from Swiss politics to this day. The call for a limit on the number of foreigners is heard again and again. A number of similar initiatives have failed. The unease about immigration was one of the reasons that the Swiss voted not to join the European Economic Area (EEA) on 6 December 1990, by a wafer-thin majority of 50.3%.

James Schwarzenbach.

ETH Library, Image Archive

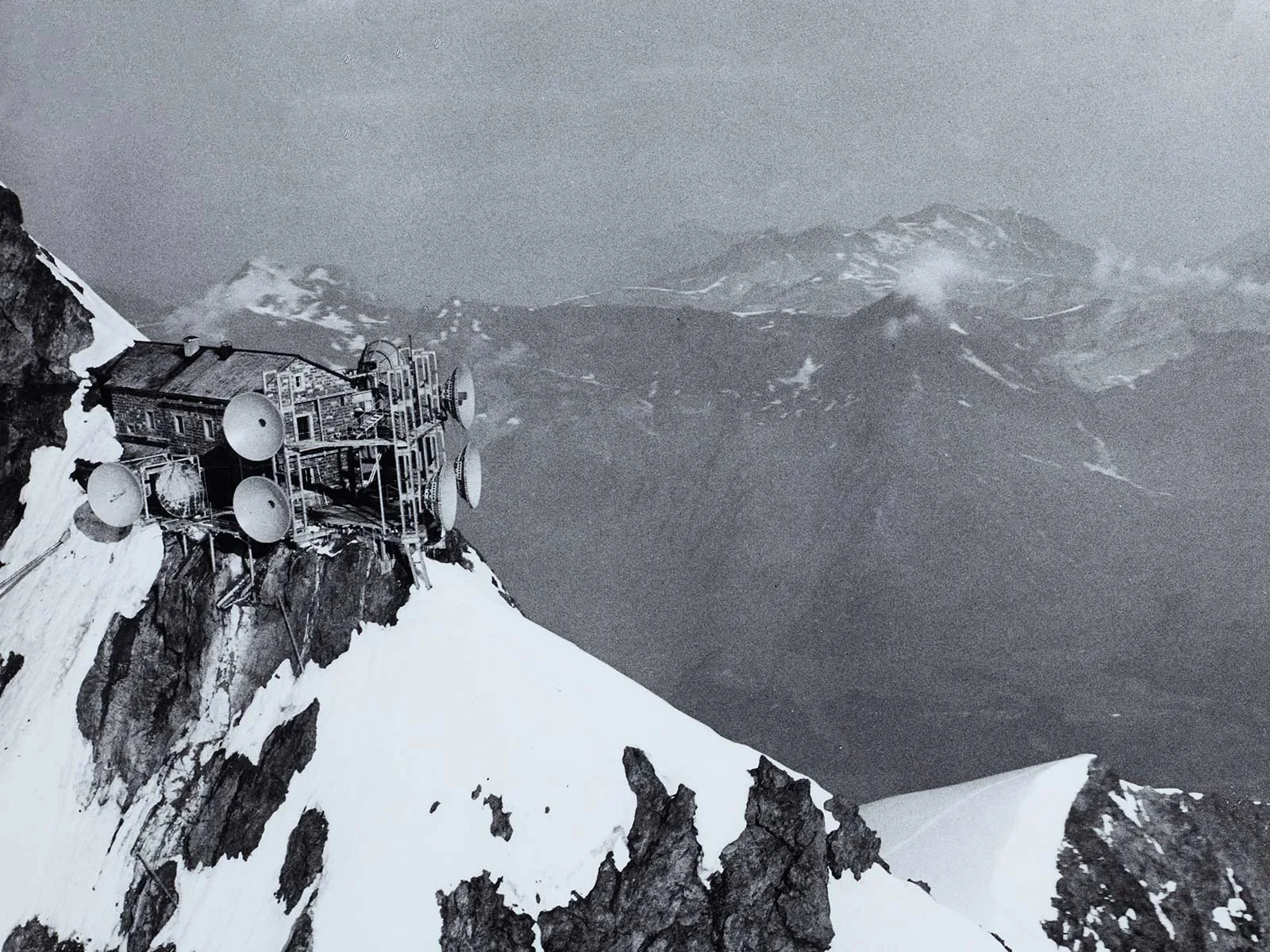

INDUSTRIALISATION LED TO A HIGHER PROPORTION OF FOREIGNERS

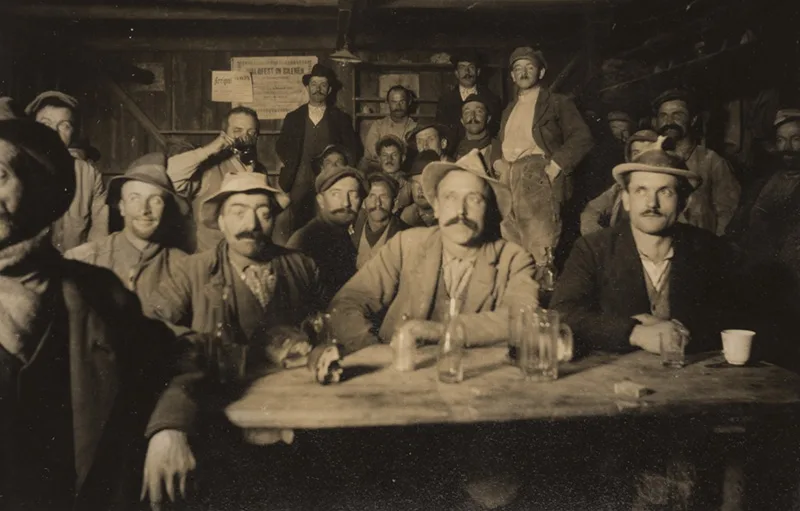

Even if the result of 7 June 1970 was a surprise to many, the debate was not new at that time: since the rise of industrialisation in the mid-19th century, Switzerland had been dependent on workers from abroad, because of the growth of the economy and the increasing needs of the industrial, building and civil engineering sectors, and also because railway lines and Alpine tunnels were being constructed. Around 1850, the proportion of foreigners was just 3%, but by 1910, it was already more than 14%. The majority of the foreign labour force lived in the cities. In 1910, foreigners made up 40% of the population of Geneva and 34% of that of Zurich. On the eve of the First World War, the high proportion of Germans in Zurich gave rise to heated debate. The Swiss writer Meinrad Inglin (1893-1971) gives a memorable description of this in his 1938 novel Schweizerspiegel (Mirror of Switzerland). However, at that time, the Italians also played a leading role in the Swiss economy, with more than 80% of railway construction workers coming from Italy. They did not always have an easy relationship with the Swiss. In 1893 and 1896 there were actual clashes between native Swiss and Italians in Bern and Zurich, which have gone down in history as the Käfigturmkrawall (Prison Tower riot) and Italienerkrawall (Italian riot) respectively.

The term ‘excessive immigration’ (Überfremdung) made its first appearance in 1910, in a brochure written by Zurich social welfare officer Carl Alfred Schmid. Although Switzerland pursued a relatively liberal immigration policy until 1914, the brakes were then applied. The argument that Switzerland’s cultural identity was under threat was repeated again and again. It is in that context that we should consider the foundation of the Immigration Police in 1917. From that point on, it regulated and monitored foreign citizens. However, other voices have also made themselves heard: in 1965, the writer Max Frisch wrote in a famous essay, ‘We asked for workers. We got people instead.’ The Italian press has also criticised the inhuman conditions endured by seasonal workers, in overcrowded, overpriced barracks on the edge of Swiss cities.

Guest workers in the canteen. Taken in 1921 during construction of the tunnels for the Amsteg power station.

Swiss National Museum

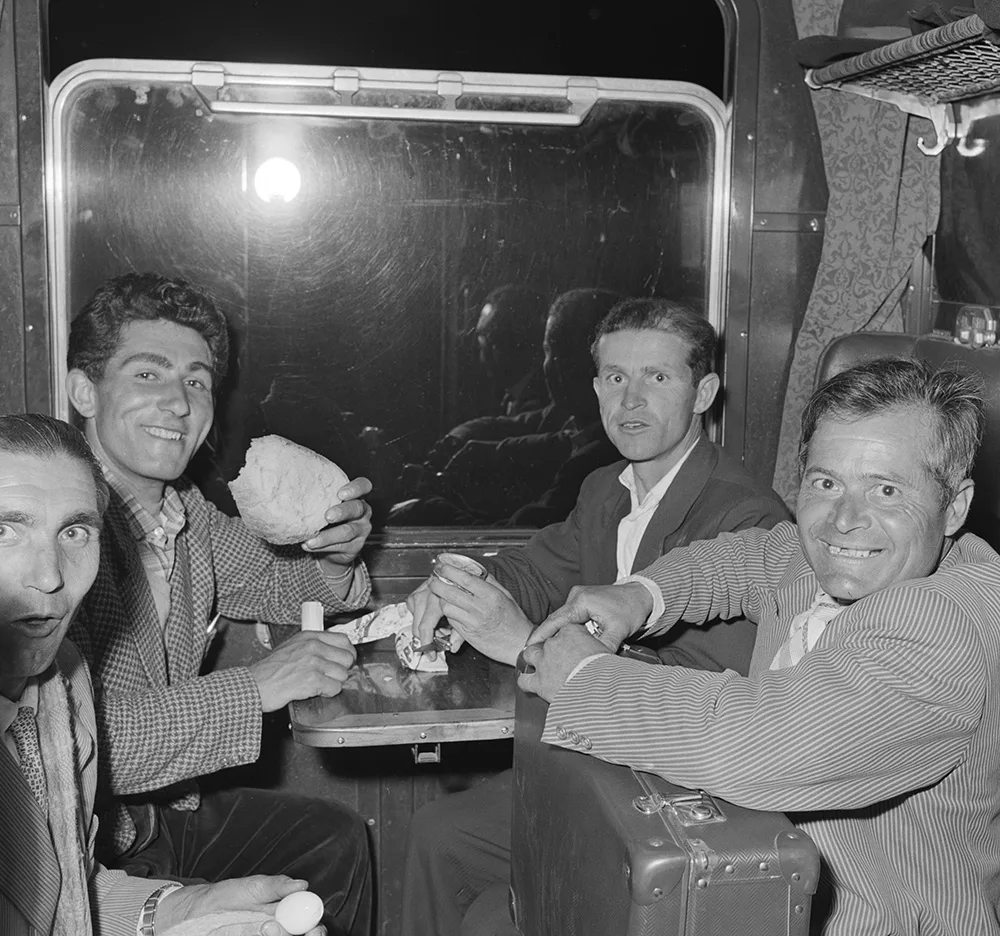

Italian guest workers travel to their homeland for elections, May 1958.

Swiss National Museum / ASL

Until the bilateral treaties with the European Union were adopted, every worker from abroad needed a permit. Many were only allowed to stay for one season at a time. These rules were abolished when Switzerland signed the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons and the bilateral agreements with the EU in 1999. Both Switzerland and Italy now consider the migration of Italian workers a successful process. Since the 1980s, the main focus of the discussion has shifted from policy on foreigners to asylum policy. How the country engages with Islam has also become more important. Racism and xenophobia have proven difficult to eradicate – but with the Anti-racism Act of 1995, Switzerland is managing these issues more effectively.

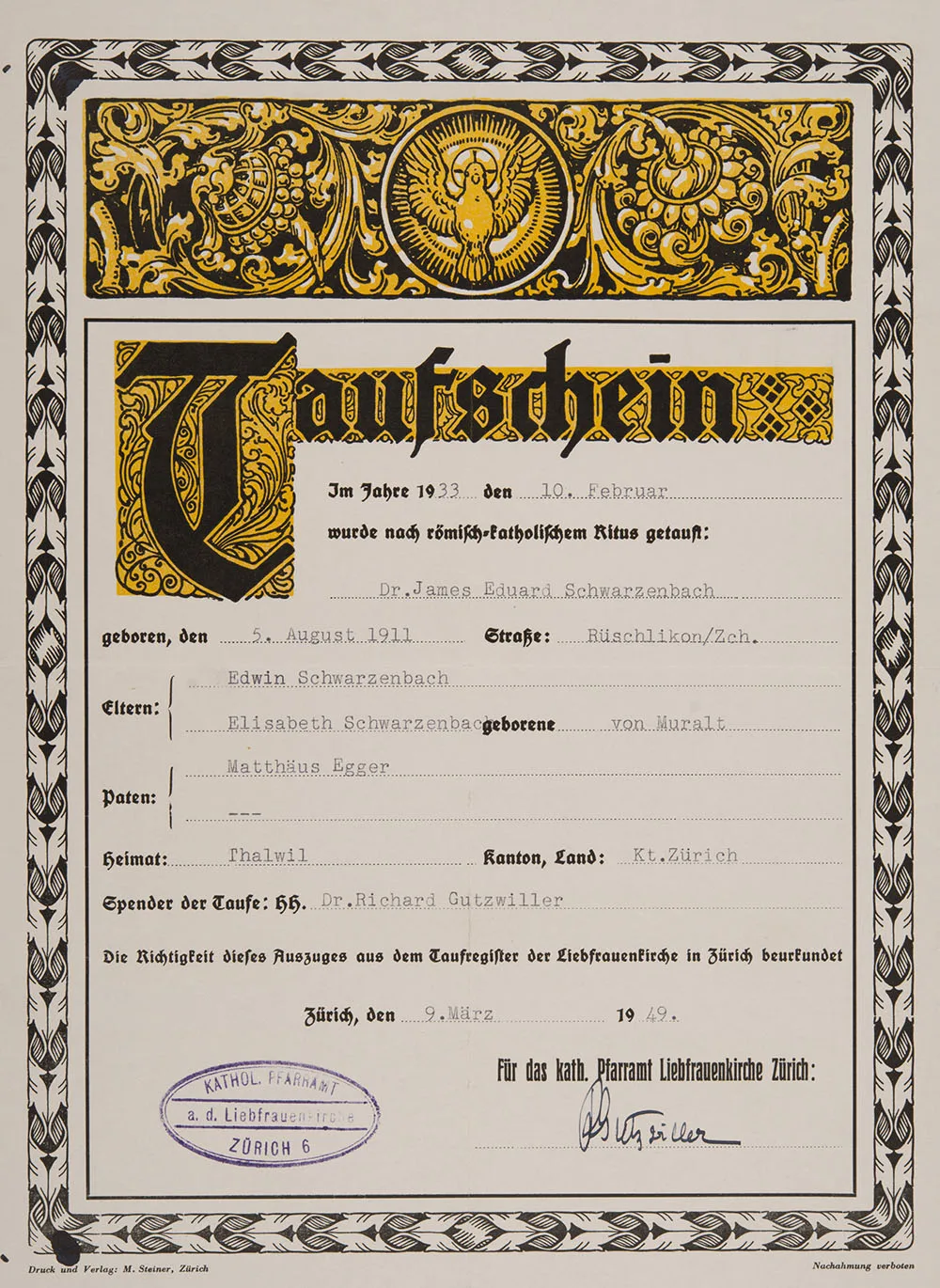

Baptismal certificate: James Schwarzenbach, born in 1911, was baptised a Catholic in 1933.

Swiss National Museum

TV documentary about the Schwarzenbach Initiative.

Swissinfo