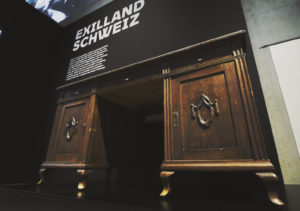

Fleeing to Switzerland

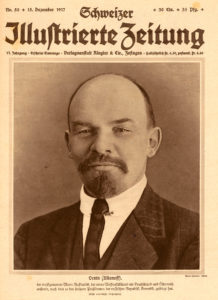

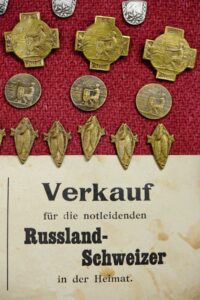

The war between Russia and Ukraine is driving people westwards. But Switzerland is an old hand at helping refugees from Eastern Europe, as a look back at the past shows.

TV documentary about the 1956 uprising in Hungary. YouTube / BBC