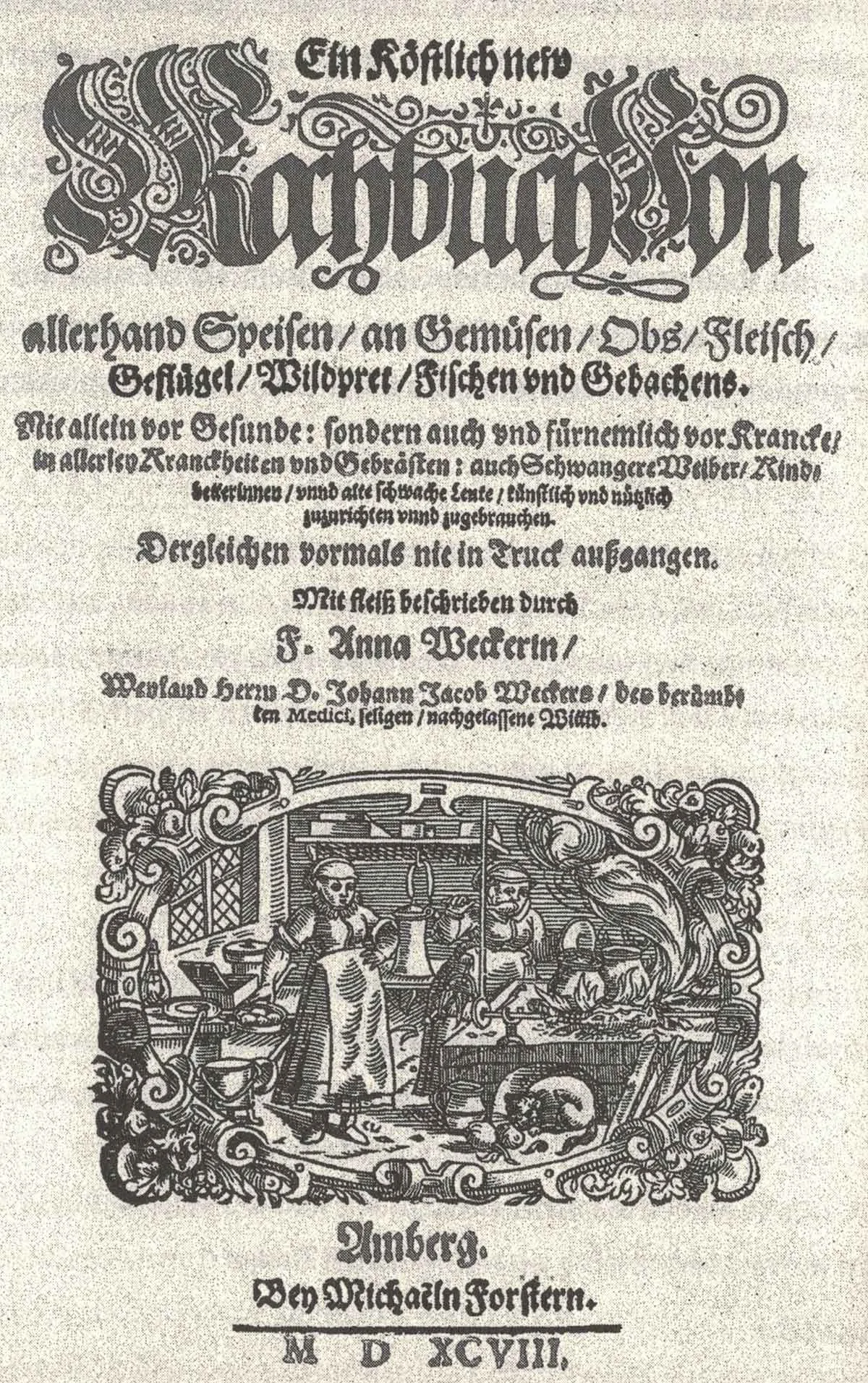

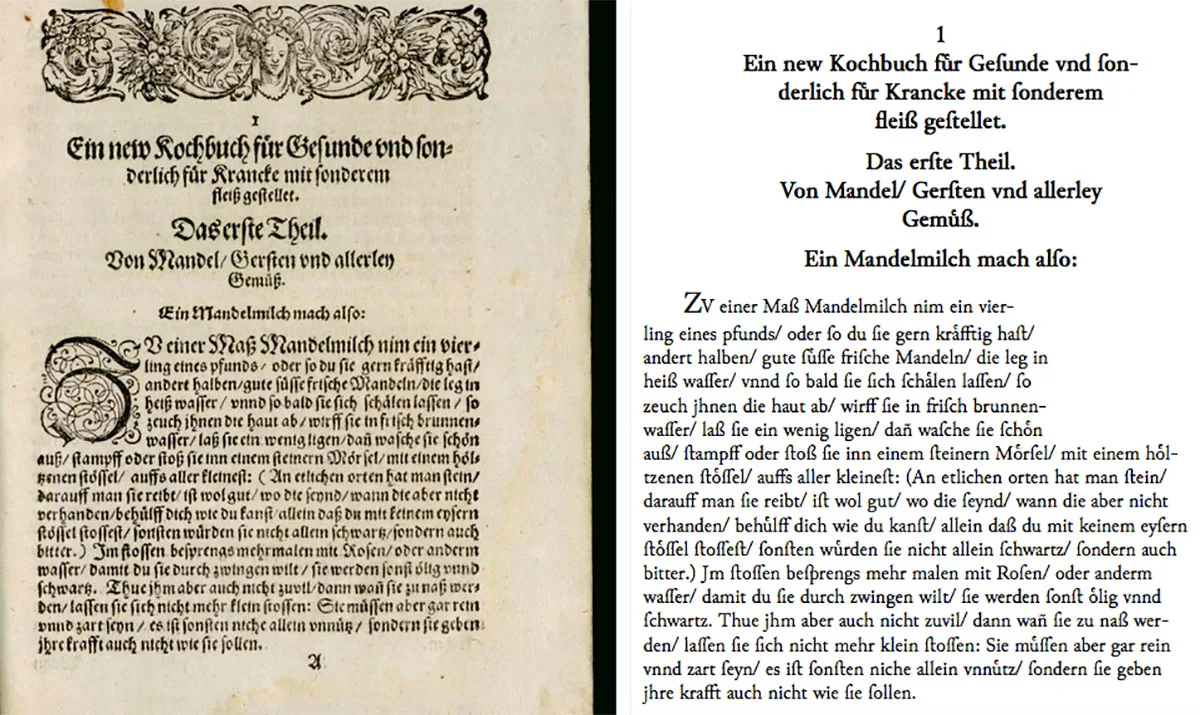

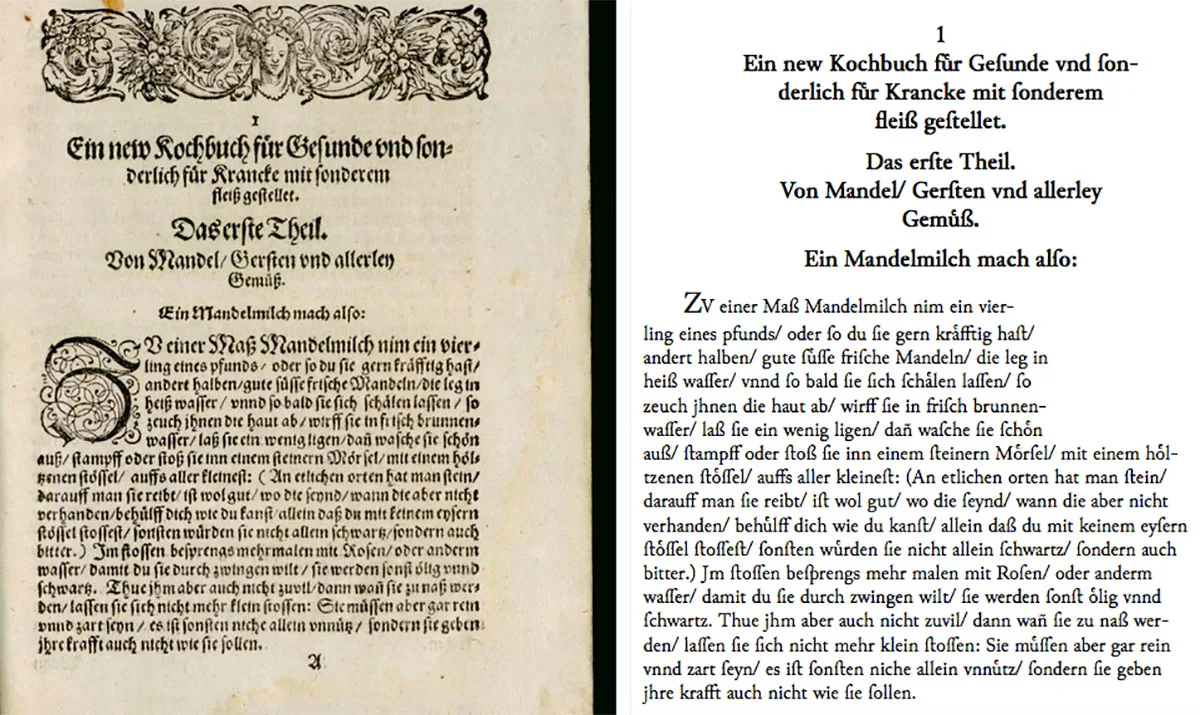

The almost-pioneer from Basel

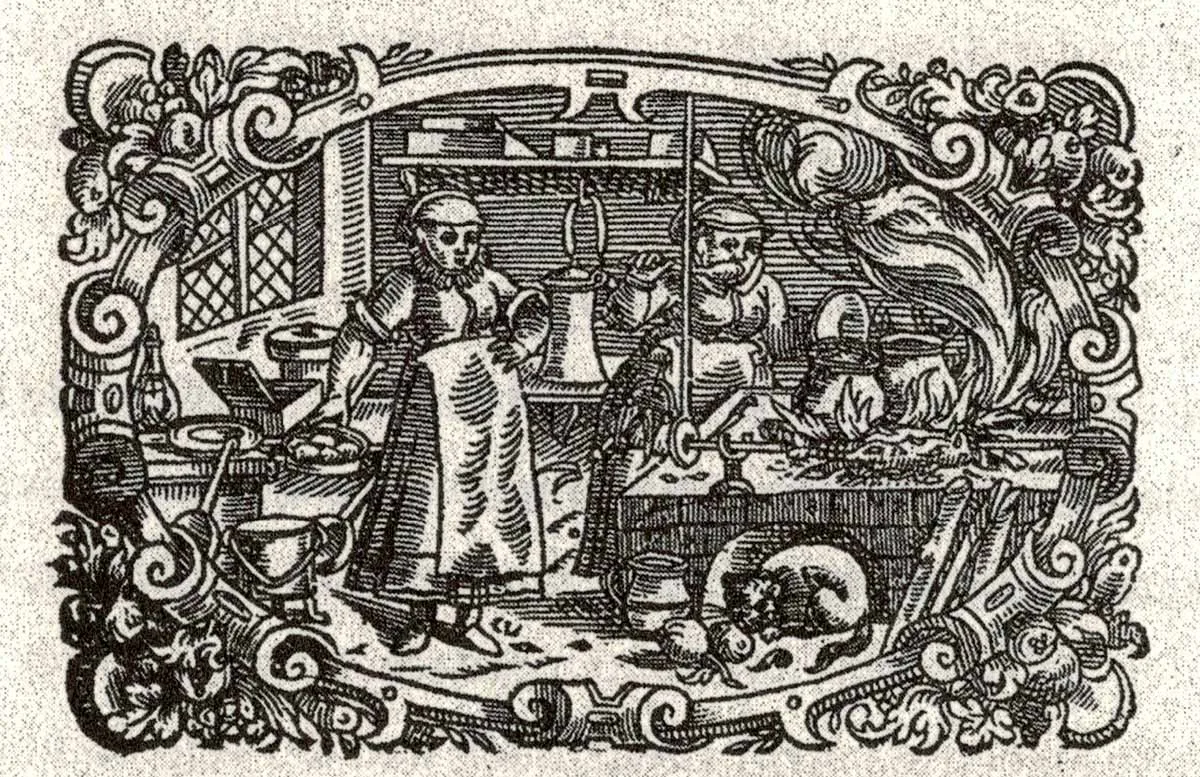

Anna Wecker from Basel is Switzerland’s first known cookbook author. She infiltrated this male-dominated sphere in 1598.

Anna Wecker from Basel is Switzerland’s first known cookbook author. She infiltrated this male-dominated sphere in 1598.