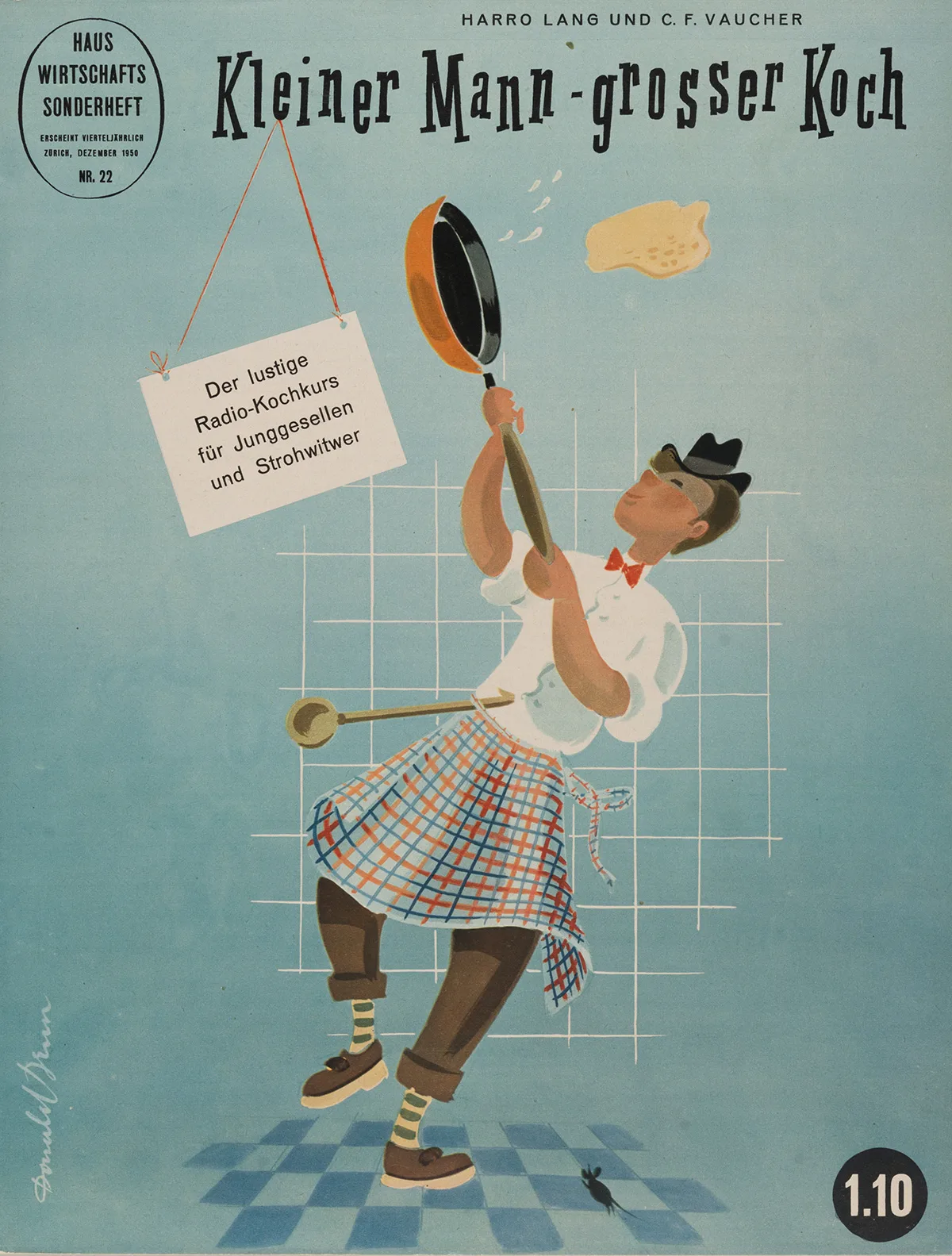

A man at the stove

What images of a man’s role were disseminated in Switzerland’s mainstream visual media in the 1950s? After World War II ended, people were looking for alternatives to the traditional image of the family man, and a lot of men found themselves standing at the kitchen stove.

Average man – great cook

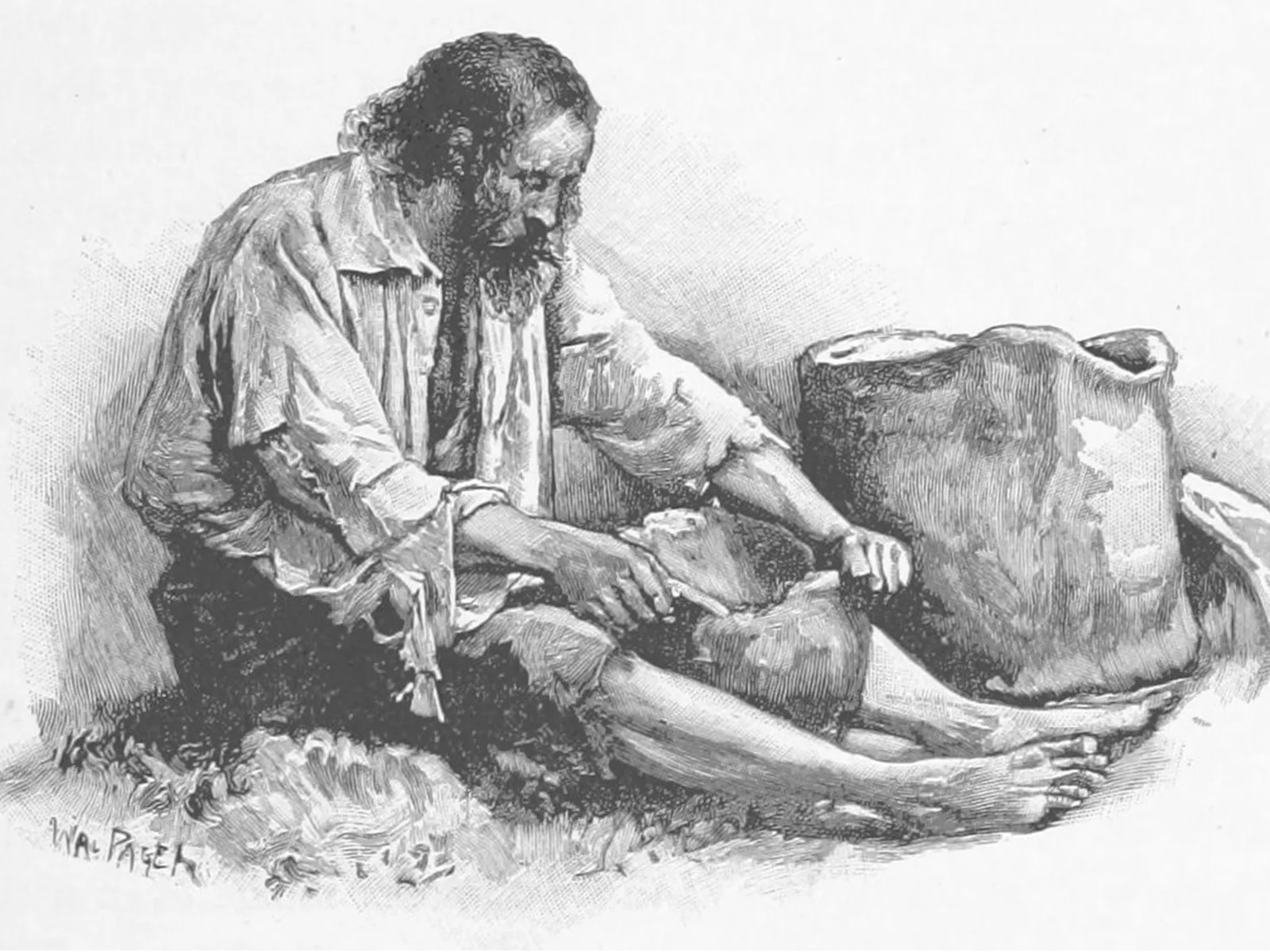

Self-sufficient provider on his island

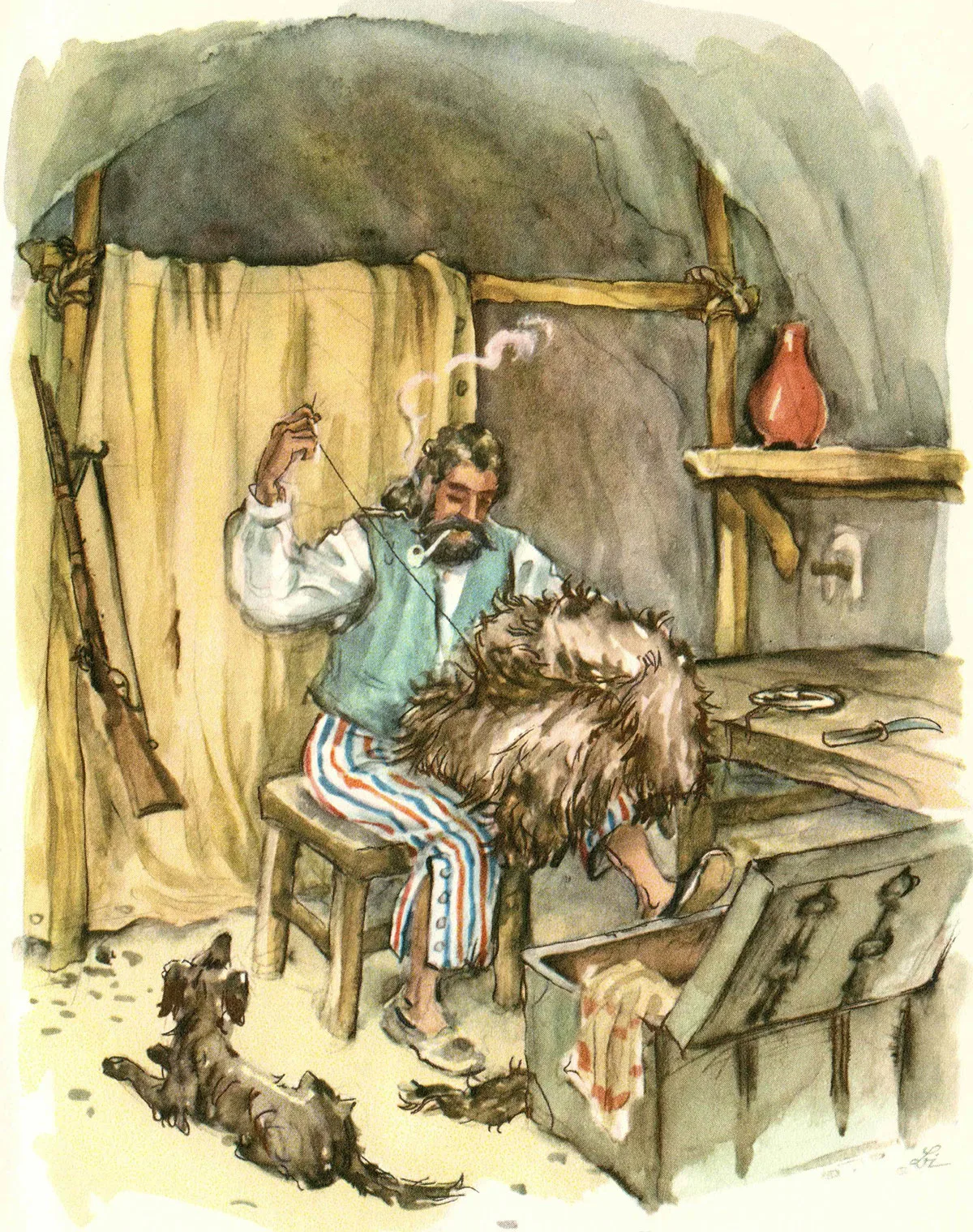

A doll’s house