Direct democracy in Switzerland

Of all the world’s democracies, Switzerland has the most extensive elements of direct democracy. The historical roots of this political structure lie in the country’s relatively well-developed educational system, and the rural uprisings of the 19th century.

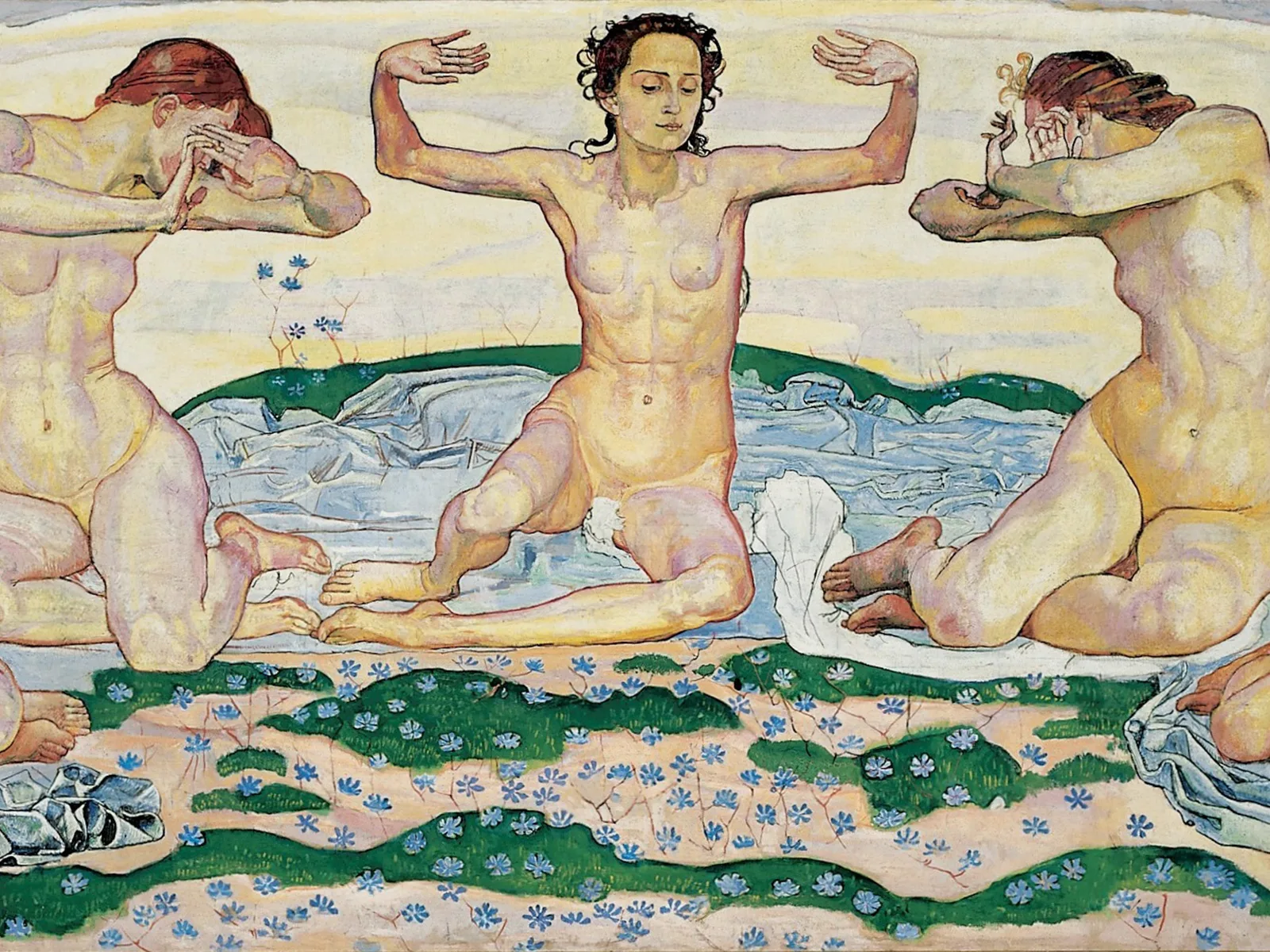

Cooperative principle, natural law and education system as a basis

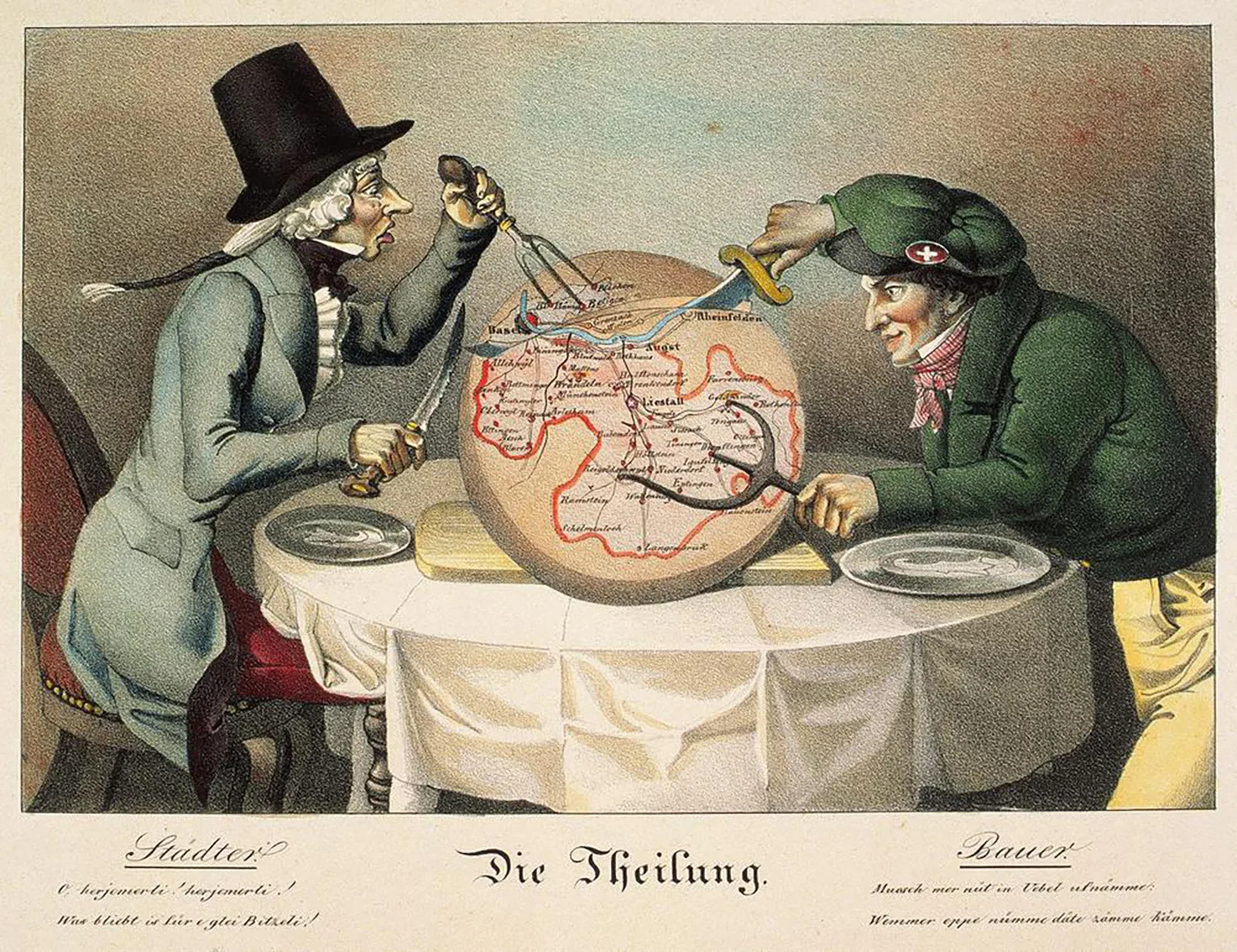

Baselland and its “movement people”

Lucerne and its “rural democrats”

A number of political currents were essential in enforcing direct democratic rights