The forgotten war hero

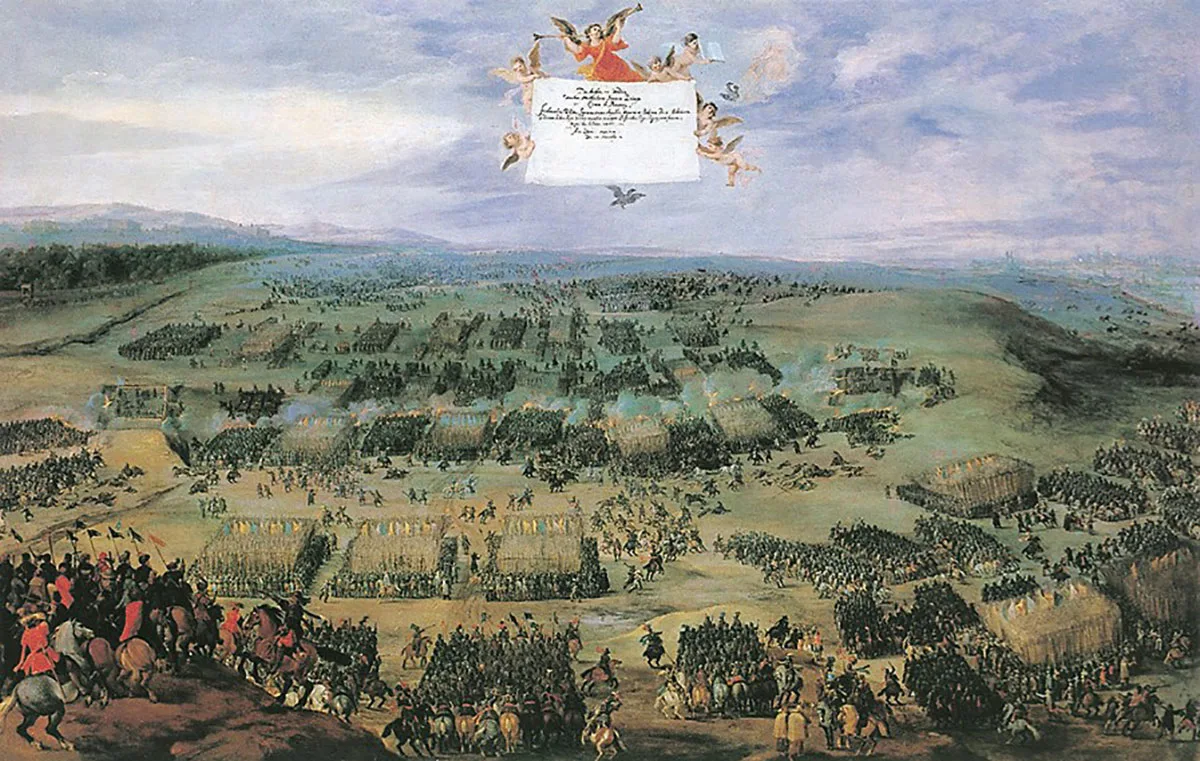

Discovered in a museum storeroom, a magnificent portrait of a horseman proves to be witness to a life straight out of an adventure novel: Fribourg mercenary leader Franz Peter König’s wild gallop through the Thirty Years’ War.

An officer and a war entrepreneur