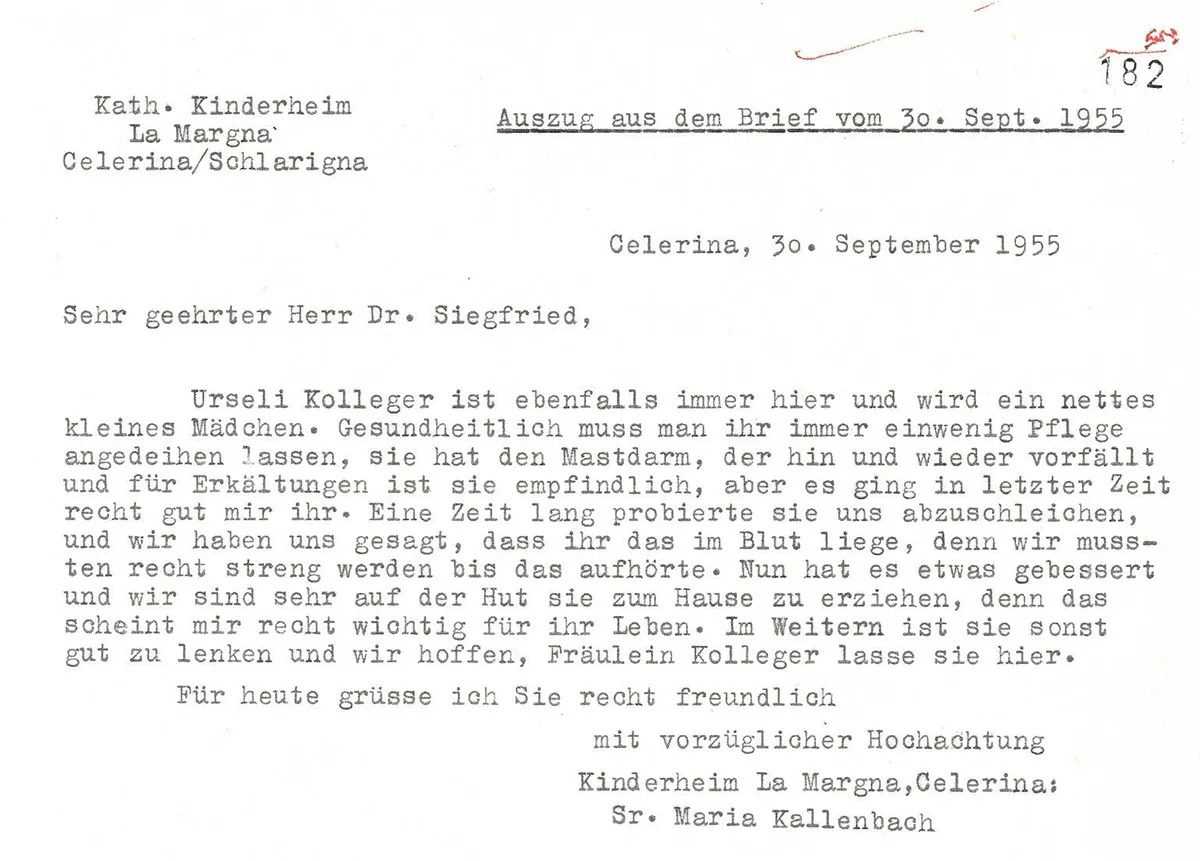

A child of the “Landstrasse”

For 18 years Ursula Waser was passed from pillar to post, through a succession of homes. Contact with her mother was forbidden and she wasn’t permitted to make any of her own decisions. The story of a child of the Landstrasse...

1972 TV report on the “Kinder der Landstrasse” campaign (in German). SRF

Care and coercion

The state has always intervened in the lives of people who were poor or did not conform to social norms. Until the 1980s, several hundred thousand children and adults were taken into care or placed in detention. Adoptions, sterilisations, forced abortions, and drug trials were performed without the knowledge or consent of those involved. Human rights were frequently ignored.

Our faces – Our stories

The multimedia online platform Our faces – Our stories looks at the lives of people who have experienced compulsory welfare measures and forced placement in foster care, and their family circle. The platform makes a crucial chapter in contemporary Swiss history digitally accessible in a new way.

Uschi Waser and 31 other direct victims of these policies, their partners and children, as well as people from the professional environment, talk about their experiences from 1947 to the present day. They talk about what happened. They name those responsible and the reasons for their treatment. They reveal the consequences with which they are still living today. The people affected also tell how they found the strength to go on living despite everything – and how they’ve fared with rebuilding their lives.

The online platform places the experiences in their historical context, and paints a nuanced picture of compulsory welfare measures and forced foster placement. For Our faces – Our stories, victims have worked together with historians.