A little history of the fan

Article of daily use and fashion accessory, artwork and status object: the fan has had a range of functions as varied and colourful as the history of its development, which extends far back into the past.

The development of fan manufacture in Europe

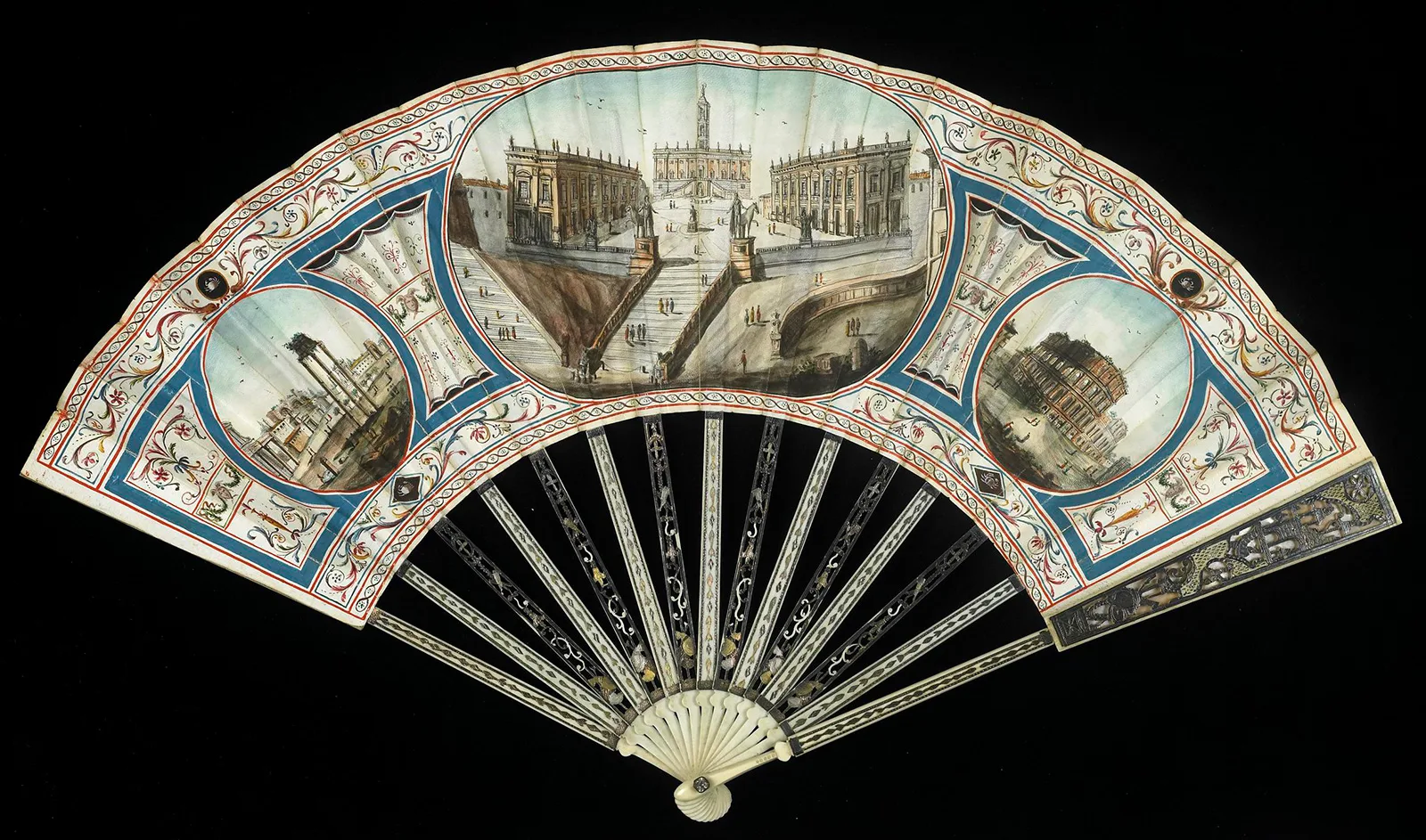

The folding fan – a portable work of art

Swiss fan painter Johannes Sulzer

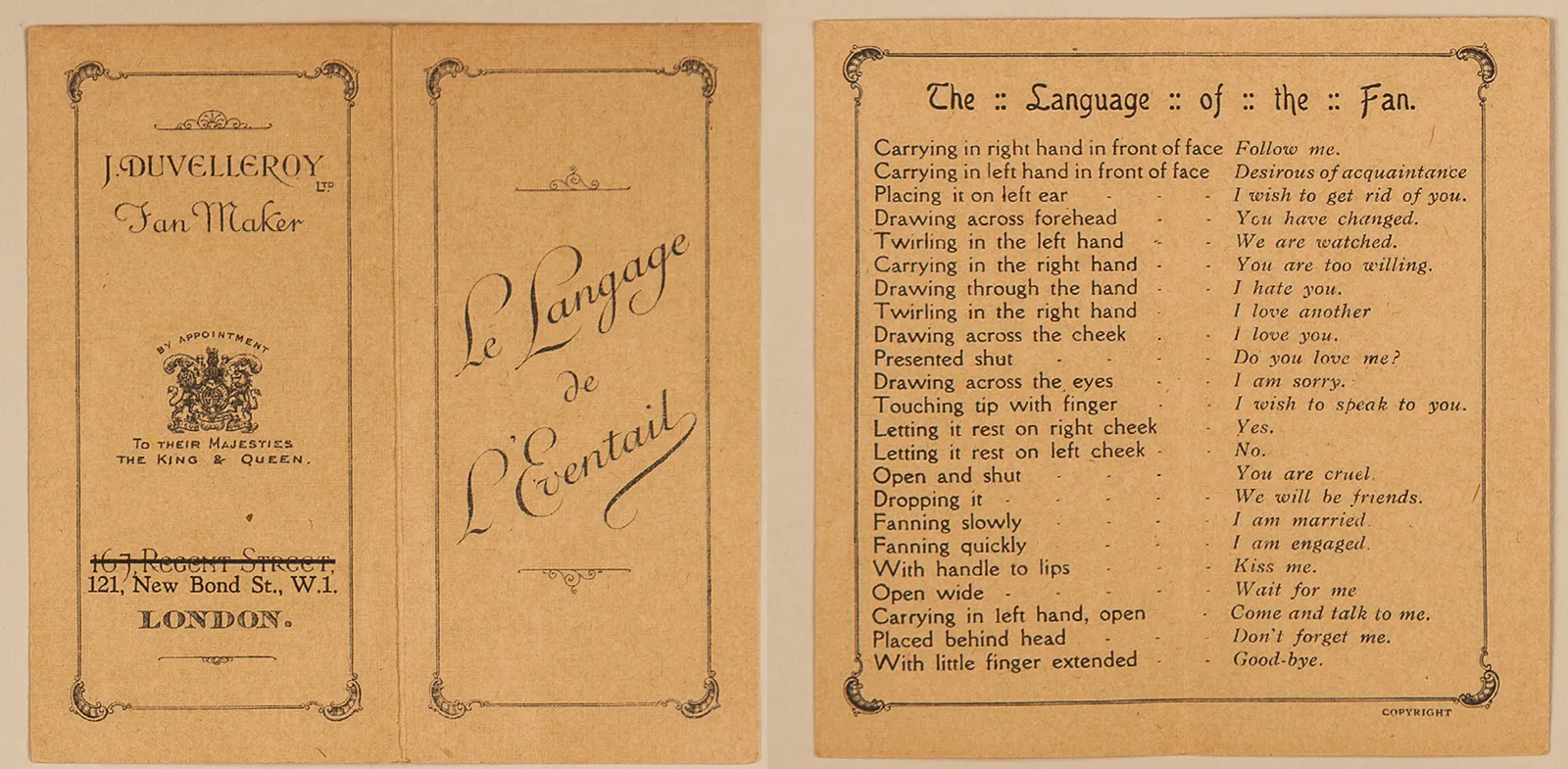

Aids in non-verbal communication

On the legendary “language of the fan”

Revival of the fan – and another fall from popularity