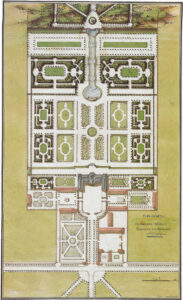

Baroque gardens in Switzerland

In France the layout of the Baroque garden was subject to strict rules, and its purpose was to illustrate power and wealth. Here in Switzerland, too, members of the aristocracy and the wealthy merchant classes constructed their gardens based on the French model – albeit with good Swiss simplicity.

The garden is continued in the interior décor: banqueting hall at Schloss Hindelbank, c. 1725. Eduard Widmer