The passions of Sir von Besenval

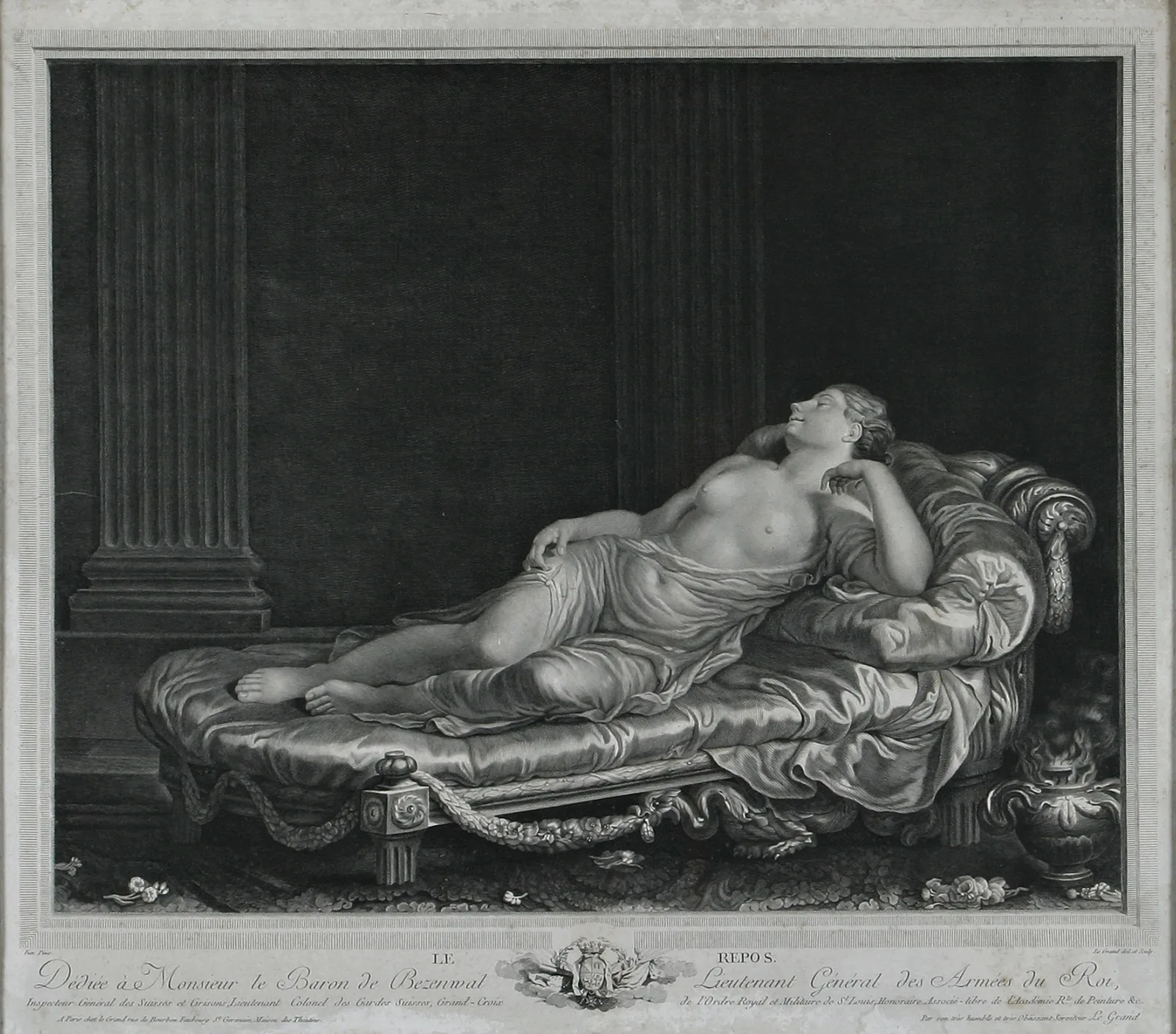

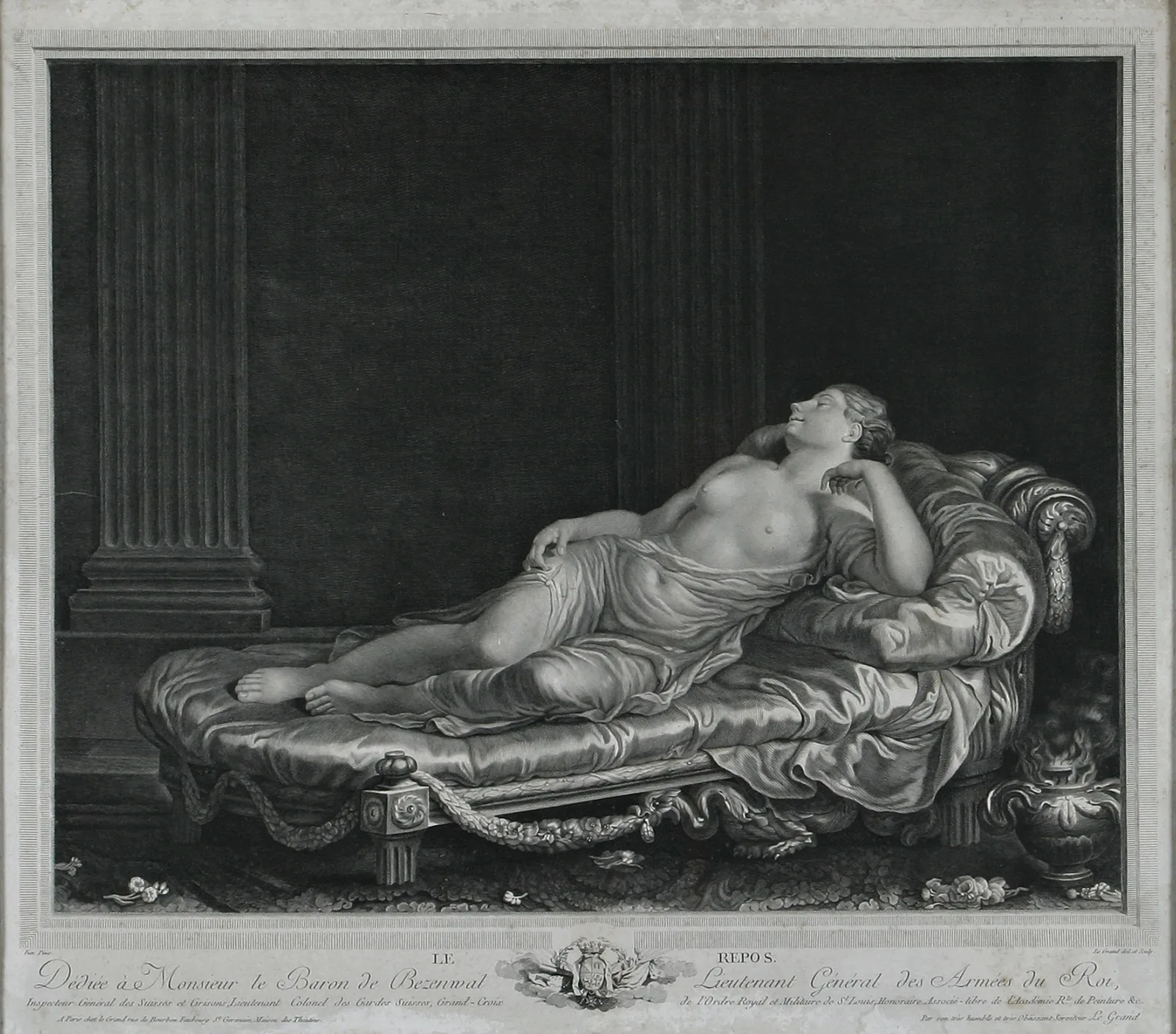

Peter Viktor von Besenval was born 300 years ago. A Swiss baron and a mercenary officer in the service of the French crown, Besenval was a passionate collector of objets d’art and plants, and a notorious ladies’ man.

![Unnumbered plate, Besenvalia senegalensis, in: Pierre-Joseph Buc’hoz, Les Dons merveilleux et diversement coloriés de la nature dans le règne végétal […], Paris, chez l’Auteur, rue de la Harpe, [1782], 2 vol., in-folio.](https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/app/uploads/besenvalia-senegalensis.webp)

Peter Viktor von Besenval was born 300 years ago. A Swiss baron and a mercenary officer in the service of the French crown, Besenval was a passionate collector of objets d’art and plants, and a notorious ladies’ man.

![Unnumbered plate, Besenvalia senegalensis, in: Pierre-Joseph Buc’hoz, Les Dons merveilleux et diversement coloriés de la nature dans le règne végétal […], Paris, chez l’Auteur, rue de la Harpe, [1782], 2 vol., in-folio.](https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/app/uploads/besenvalia-senegalensis.webp)