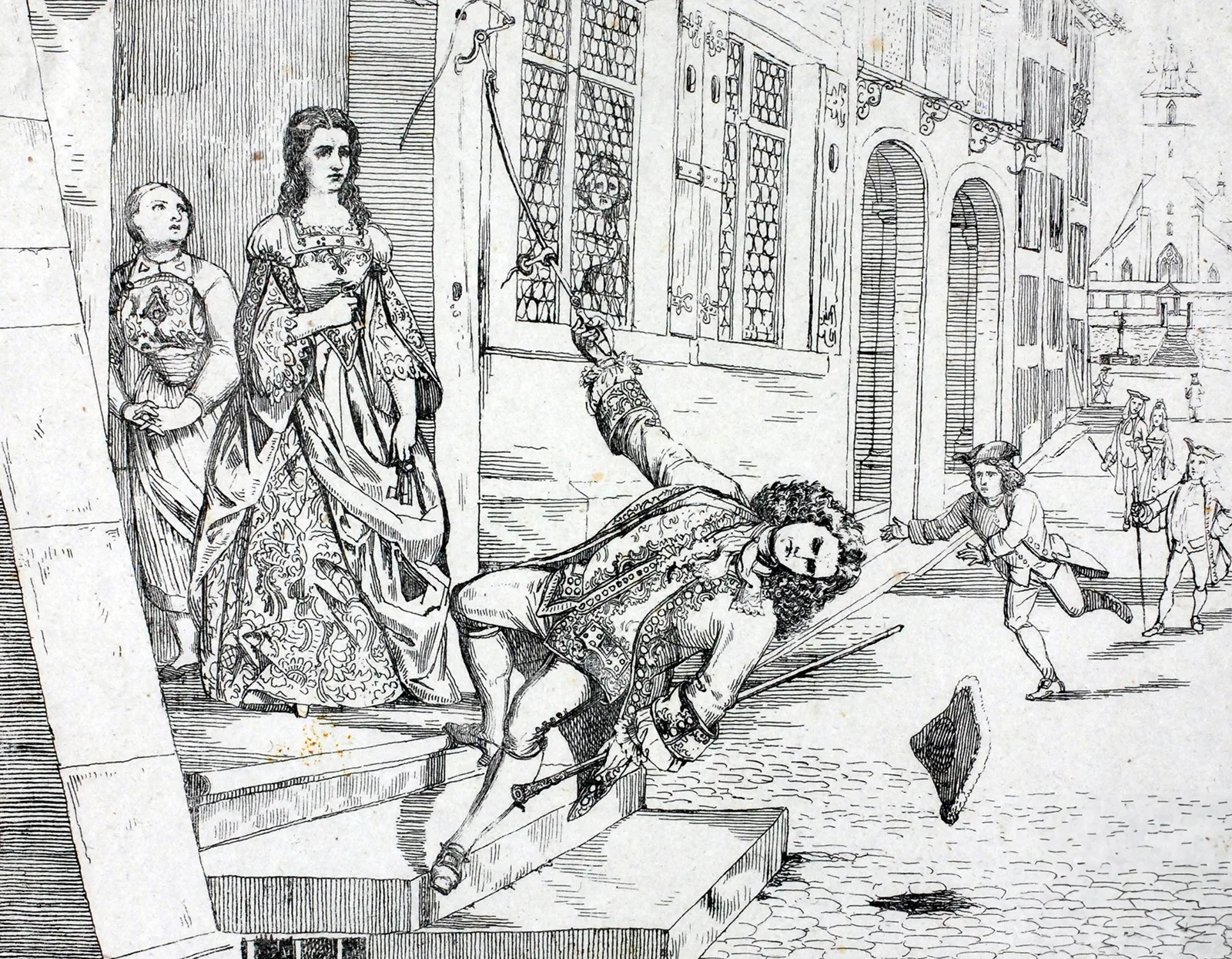

This one died at the garden fence, that one on the doorstep

An argument between two former friends from the patrician class in Solothurn was the undoing of both opponents and plunged a mother into hopeless despair.

What had happened?

This one could well keep quiet! He does not belong here by right and is not worthy to wear the sword at his side.

Du Hundsfott!

Banished to St. Gallen