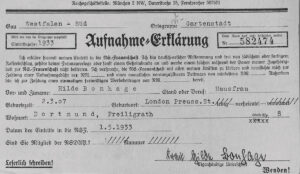

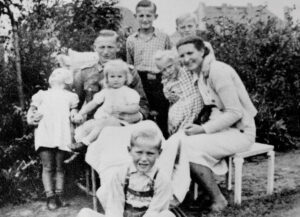

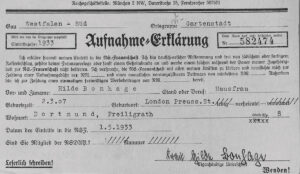

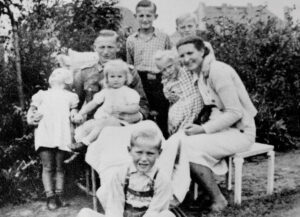

My Nazi grandmother

I learned late that my grandmother, whom I never met, was a staunch Nazi. After reading hundreds of letters, I realised with horror how much guilt she had incurred.

I learned late that my grandmother, whom I never met, was a staunch Nazi. After reading hundreds of letters, I realised with horror how much guilt she had incurred.