The Walser Migrations

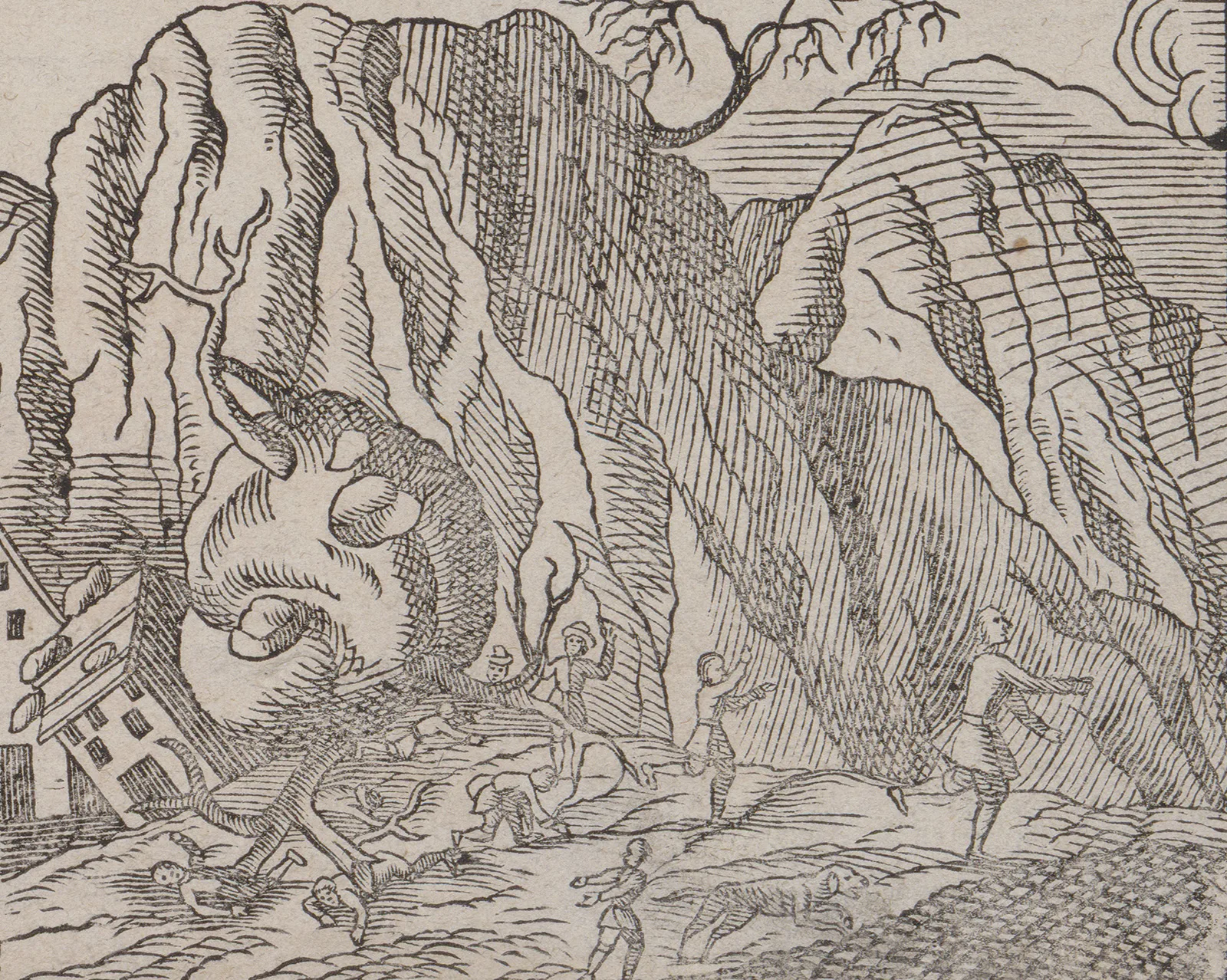

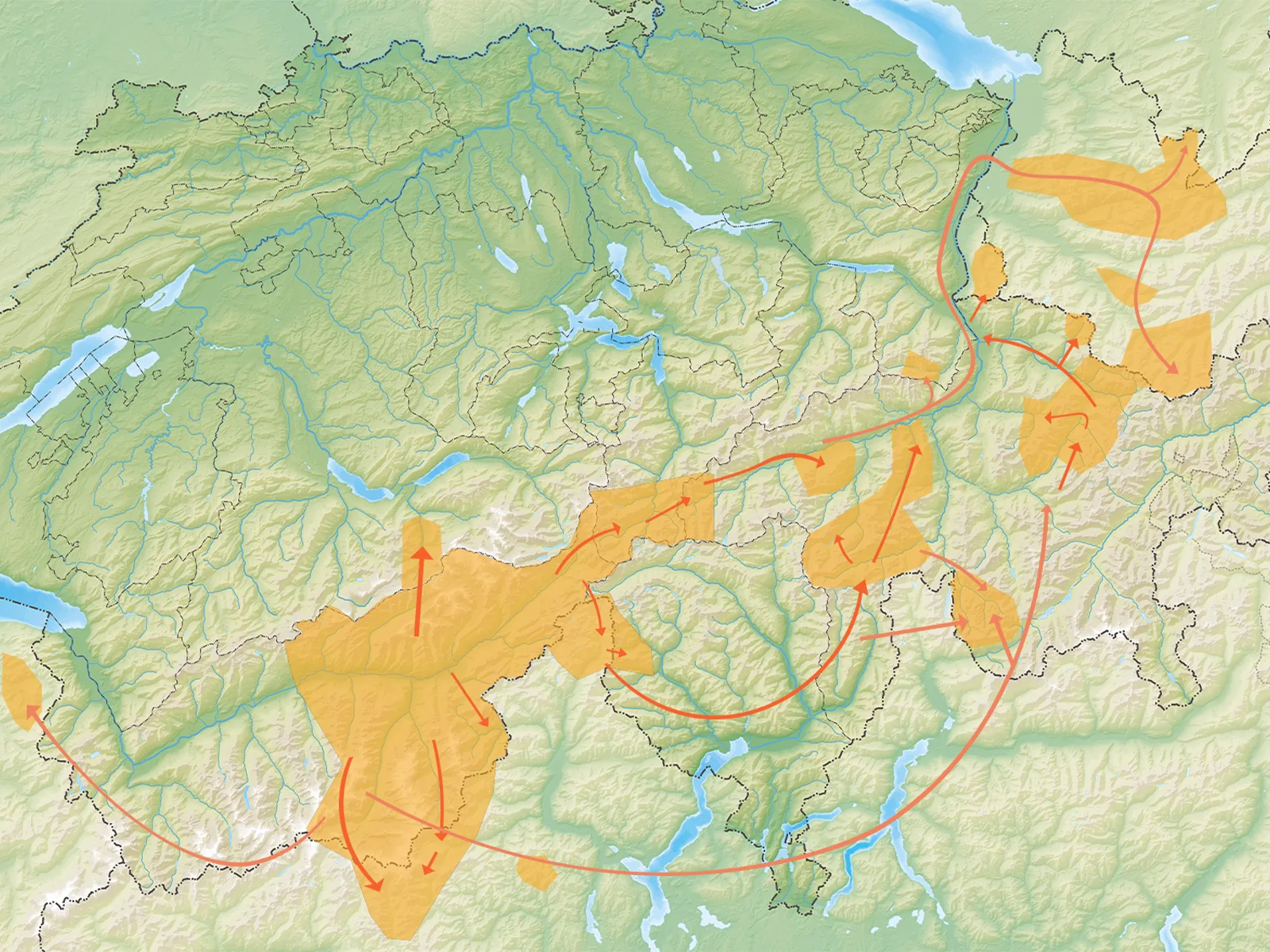

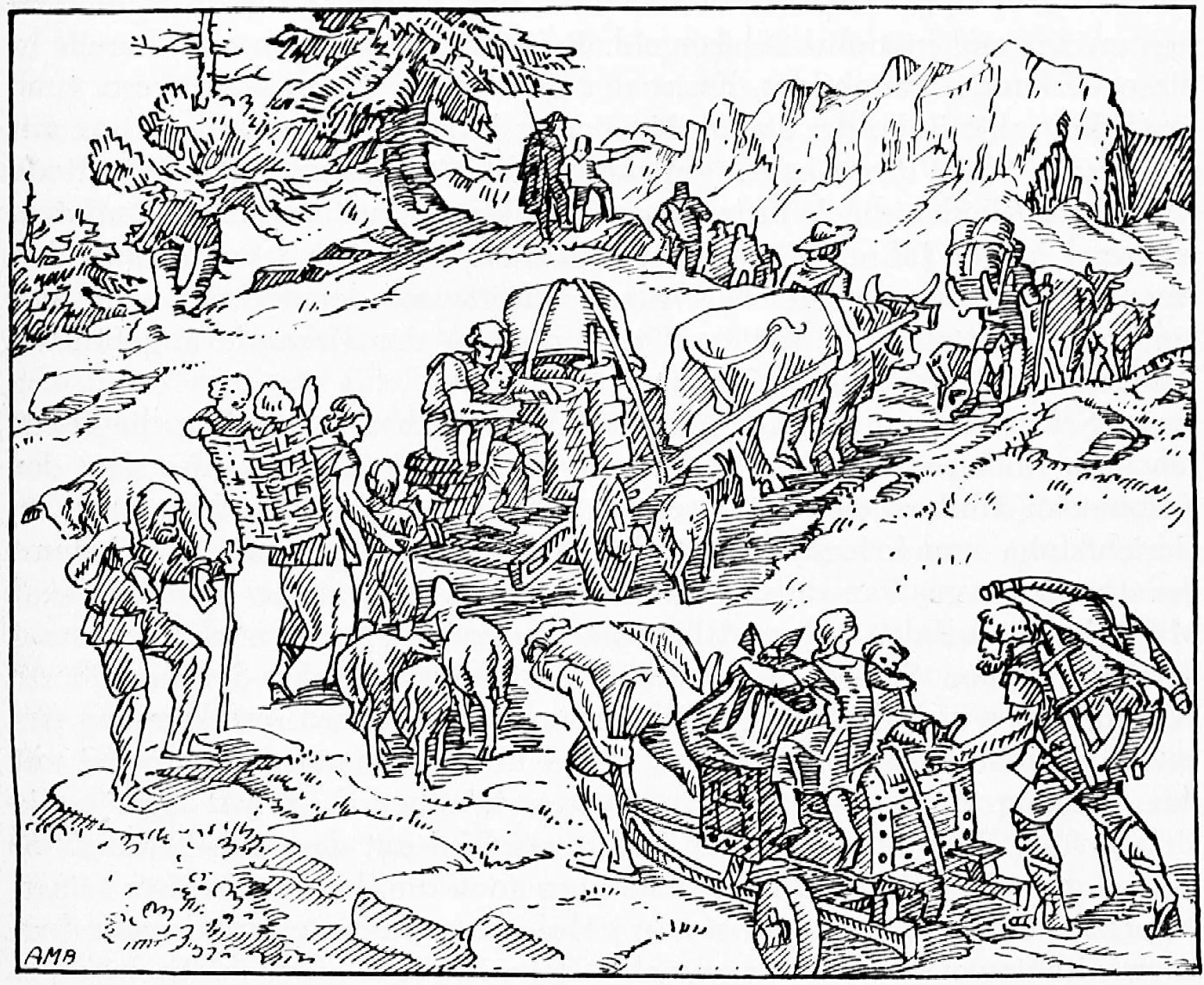

The Walsers migrated outwards to settle and tame uncultivated pastures in the harsh high altitudes of the Alps between c. 1150-1450. This migration represents one of the last great movements of peoples during the Middle Ages, and the legacy of Walser resourcefulness still looms large in Swiss culture.

Äss ischt kchei Vogil no so hoo gflogu, är hei nit Bodo bizogu.

Weer fer as güets Woort nit tüet, dem geits säältu’ güet.

Walser Traditions and Legacies

We mu de Liit der chlei Finger git, welluntsch di ganzi Hant.