The beginnings of the modern fashion system

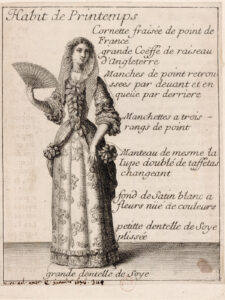

The forerunners of the first fashion magazines were published in Paris during the reign of Louis XIV. Like their modern counterparts, they pictured seasonal fashion trends, and helped to create the fashion system as we know it today.

Flourishing French fashion press

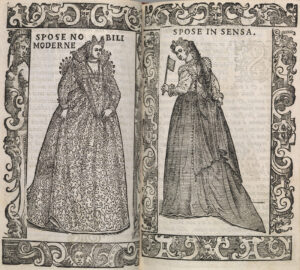

Part portrait, part fashion plate

Mercure galant – forerunner of the first fashion magazines

The seasonal rhythm of fashion