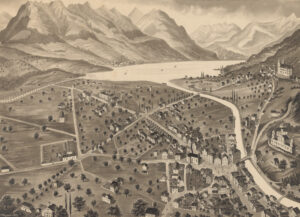

Sarnen – History at a scale of 1:1

A walking tour of Obwalden’s principal town. A connection, a story, emerges from the juxtaposition of locations and features. It recounts the history of a dynasty, typical for Central Switzerland, embodied in buildings. Four generations of Imfelds.

Mark out the area

Places have voices

Almost out of nowhere

A visual embodiment of the family’s superior status

Dealing in mercenaries

Ancient origins for young aristocracy

Gentlemen and peasants