24 calories for Cinderella

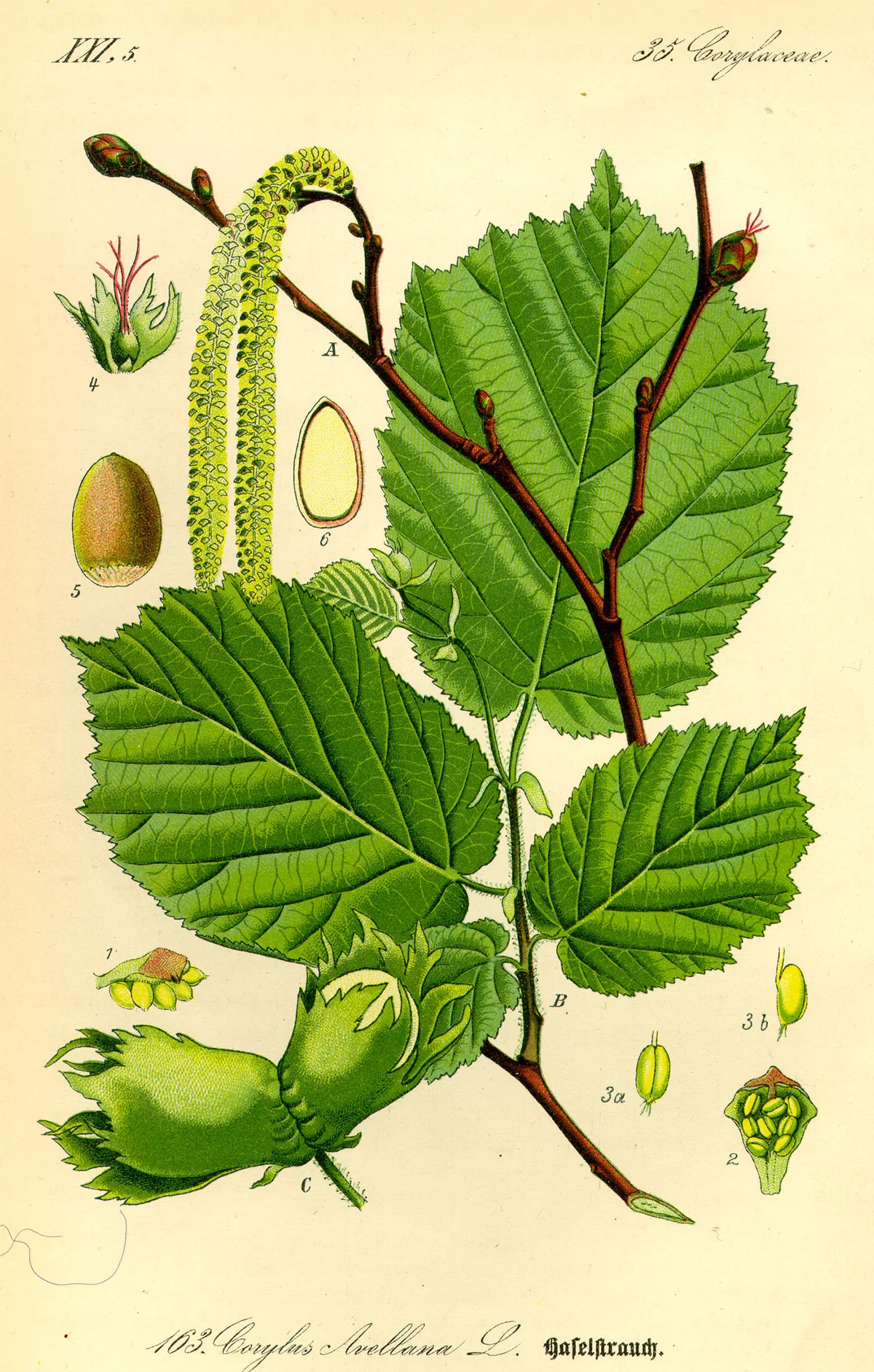

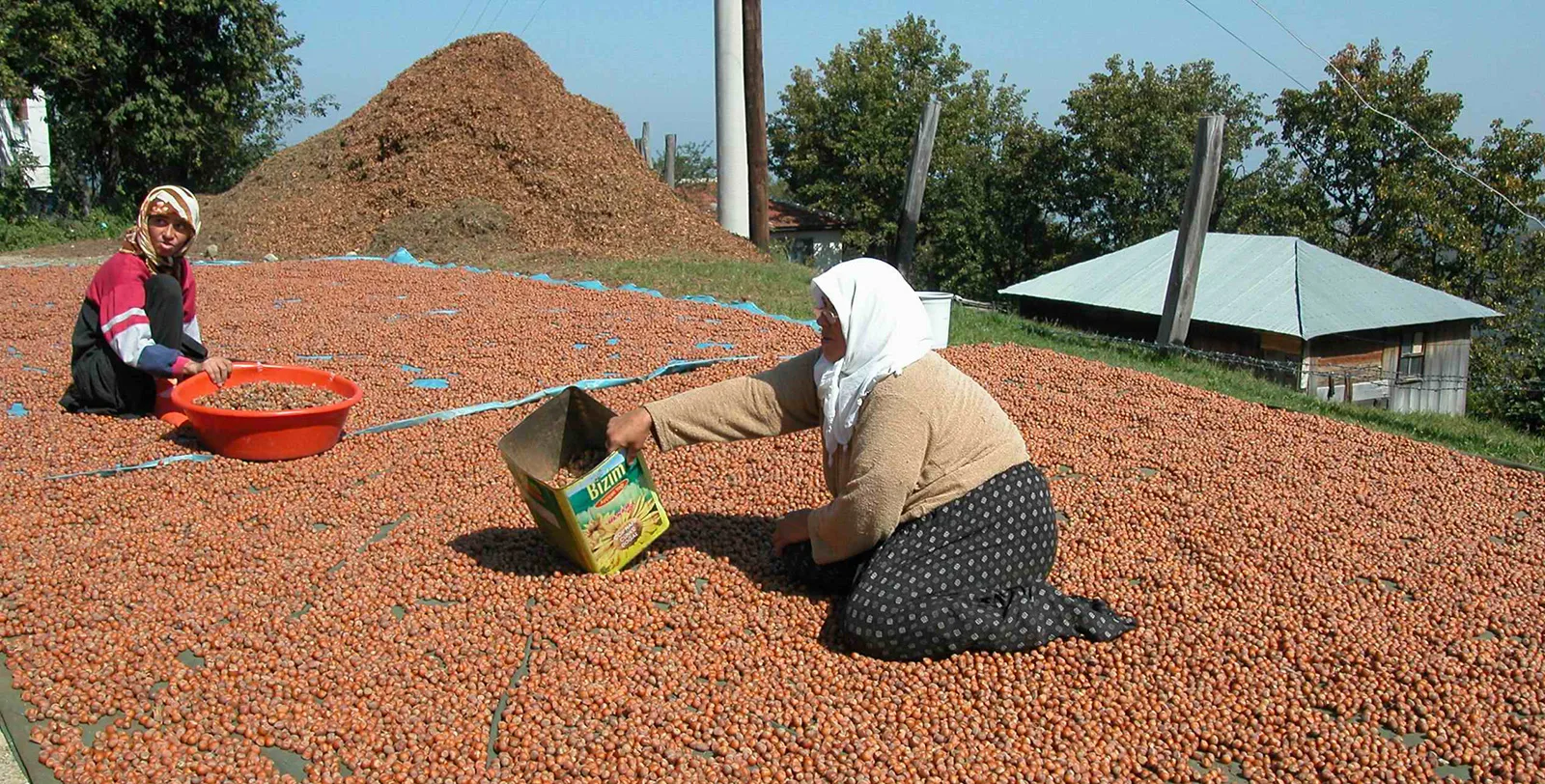

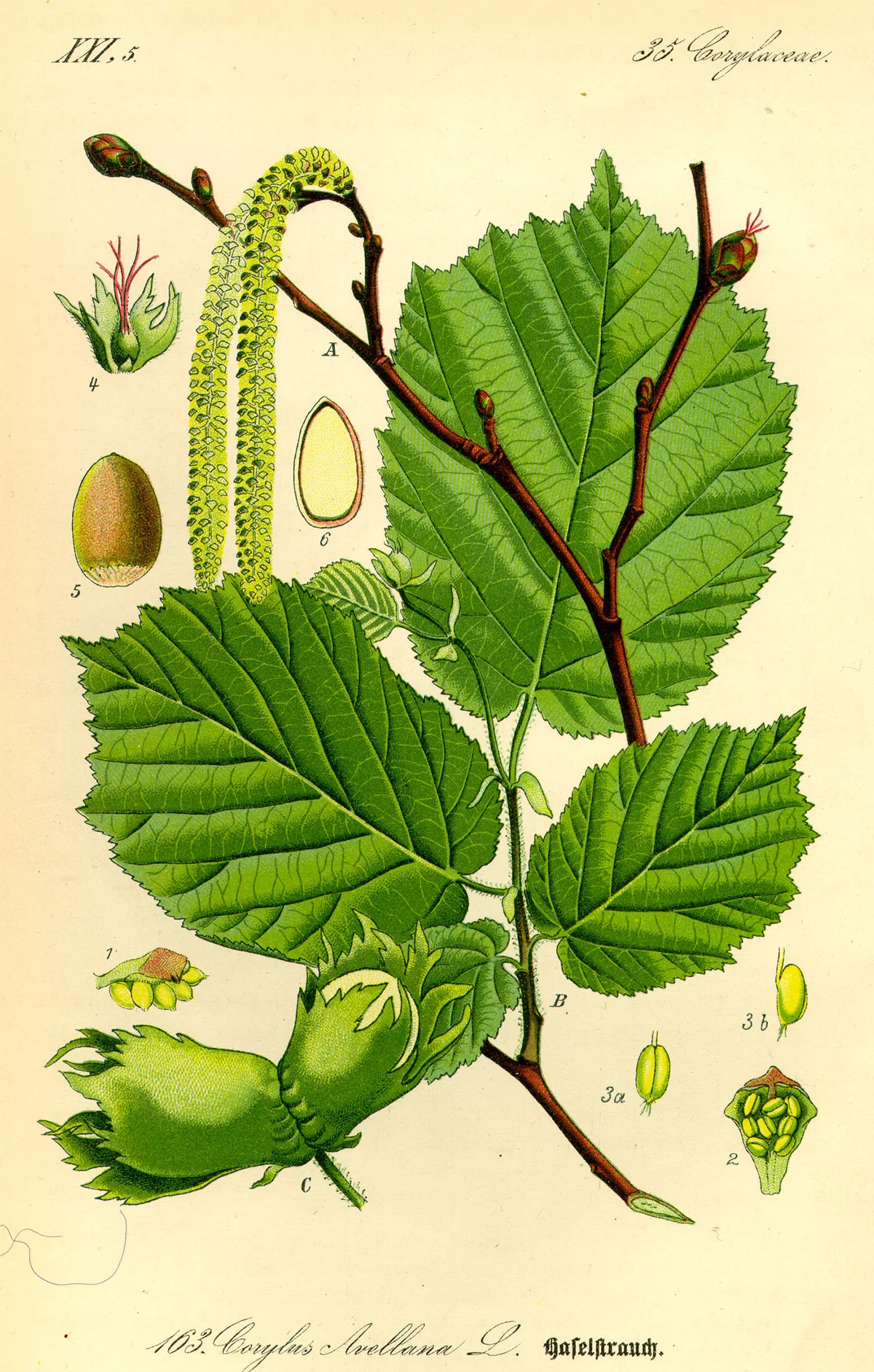

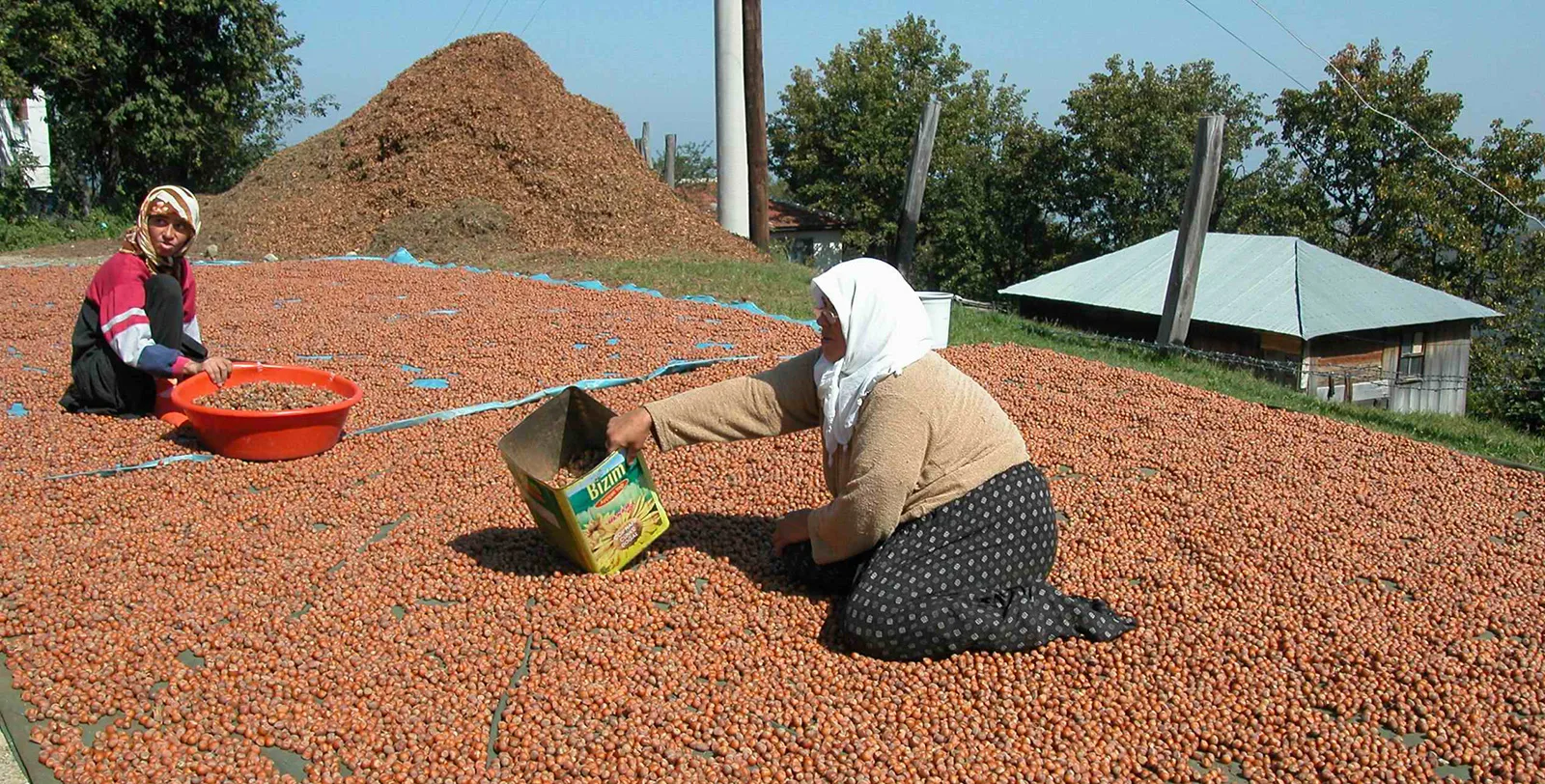

"Drei Haselnüsse für Aschenbrödel": in the 1973 Czech-German fantasy film, three enchanted hazelnuts make all the heroine’s dreams come true. But even without any magic, the hazelnut is a remarkable fruit.

"Drei Haselnüsse für Aschenbrödel": in the 1973 Czech-German fantasy film, three enchanted hazelnuts make all the heroine’s dreams come true. But even without any magic, the hazelnut is a remarkable fruit.