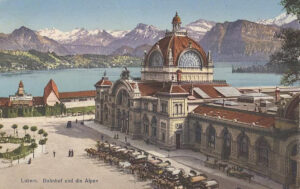

A tour of Lucerne reveals the spirit of the Belle Epoque

Swiss cities such as Lucerne experienced an epochal transformation around 1900. Its medieval centre was expanded to include prestigious residential and commercial buildings, stations, postal and administrative offices, school buildings, hotels and villas. However, architecturally this modernisation bore the hallmarks of the past. Time for a virtual tour of Lucerne.

Cathedral from the industrial era beside the historicised knight’s castle

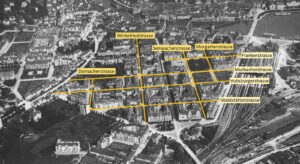

New town with old features

Sacred expressions

Simultaneity of the non-simultaneous

An archetype of sorts

An architectural visiting card

Role models and the serious side of life