O Fortuna! The wheel of fortune and luck

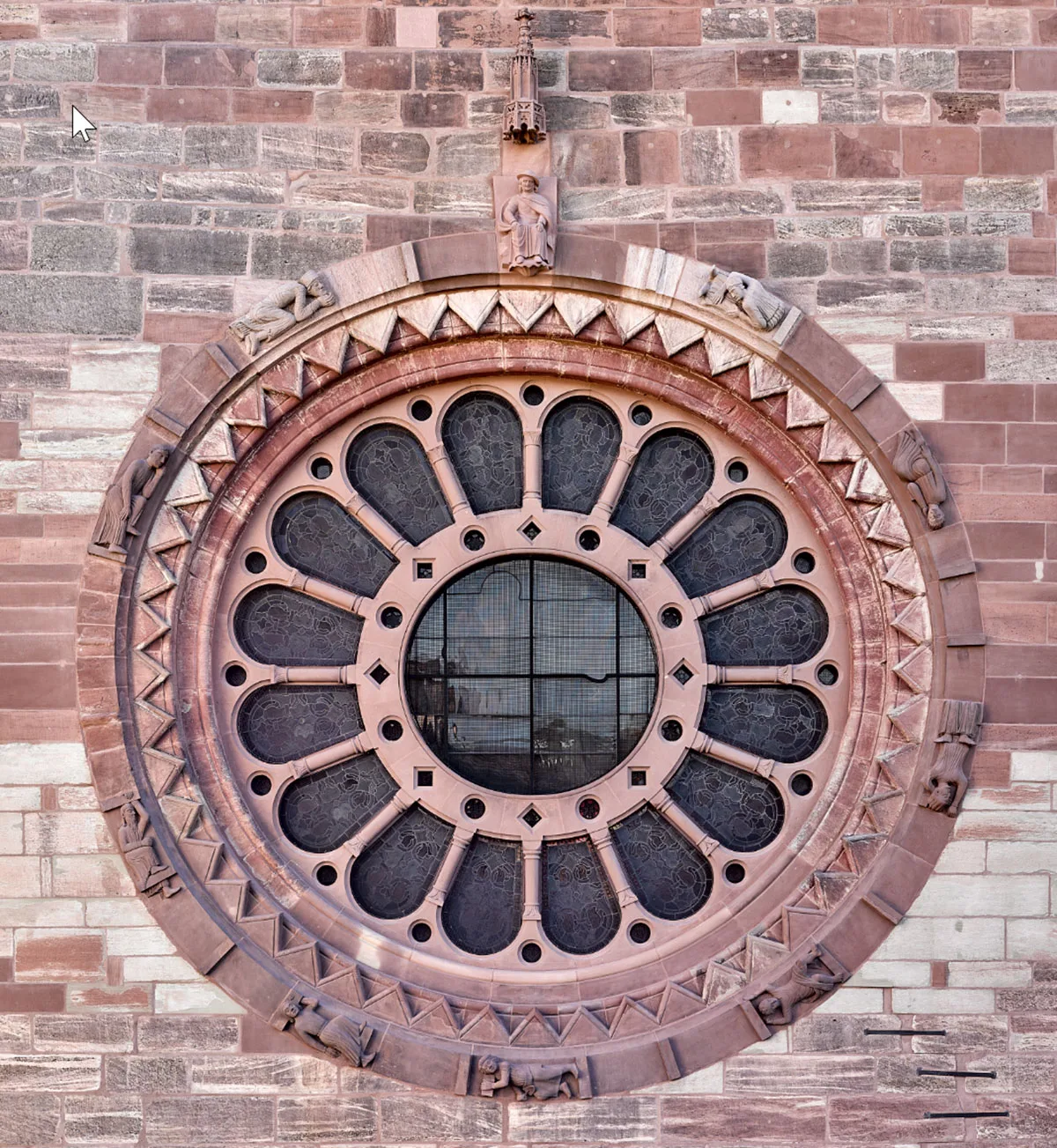

We humans are predisposed to brood over the changing nature of luck. The wheel of fortune has been turning since ancient times, and remains popular today. Around 1220, a rose window at Basel Cathedral was designed to resemble a wheel of fortune, homage was paid to the goddess Fortuna in a Bavarian monastery in the form of the Carmina Burana. Yet, undeserved luck plays no part in the Christian world view. Heavenly salvation is something that has to be earned.

But where is Fortuna?

Two master builders, identifiable by their headgear, on the wheel of fortune at Basel Cathedral. The one on the right, who is falling, fearful yet defiant, struggles to escape his impending doom; the one on the left, who is rising, slumbers peacefully, unaware of his coming good fortune. However, the two expressive figures do not belong to the same ‘generation’ and are not even to be found in the same place: the falling builder, an original dating back to 1220, is currently housed in the Museum Kleines Klingental, the ascending builder, a masterful copy created in 1986, remains in situ at Basel Cathedral. © Kantonale Denkmalpflege Basel-Stadt und Münsterbauhütte Basel / Peter Schulthess

What is original at the original location?

“Oh Fortune, like the moon you are changeable, ever waxing and waning!”

Sors immanis et inanis,

rota tu volubilis

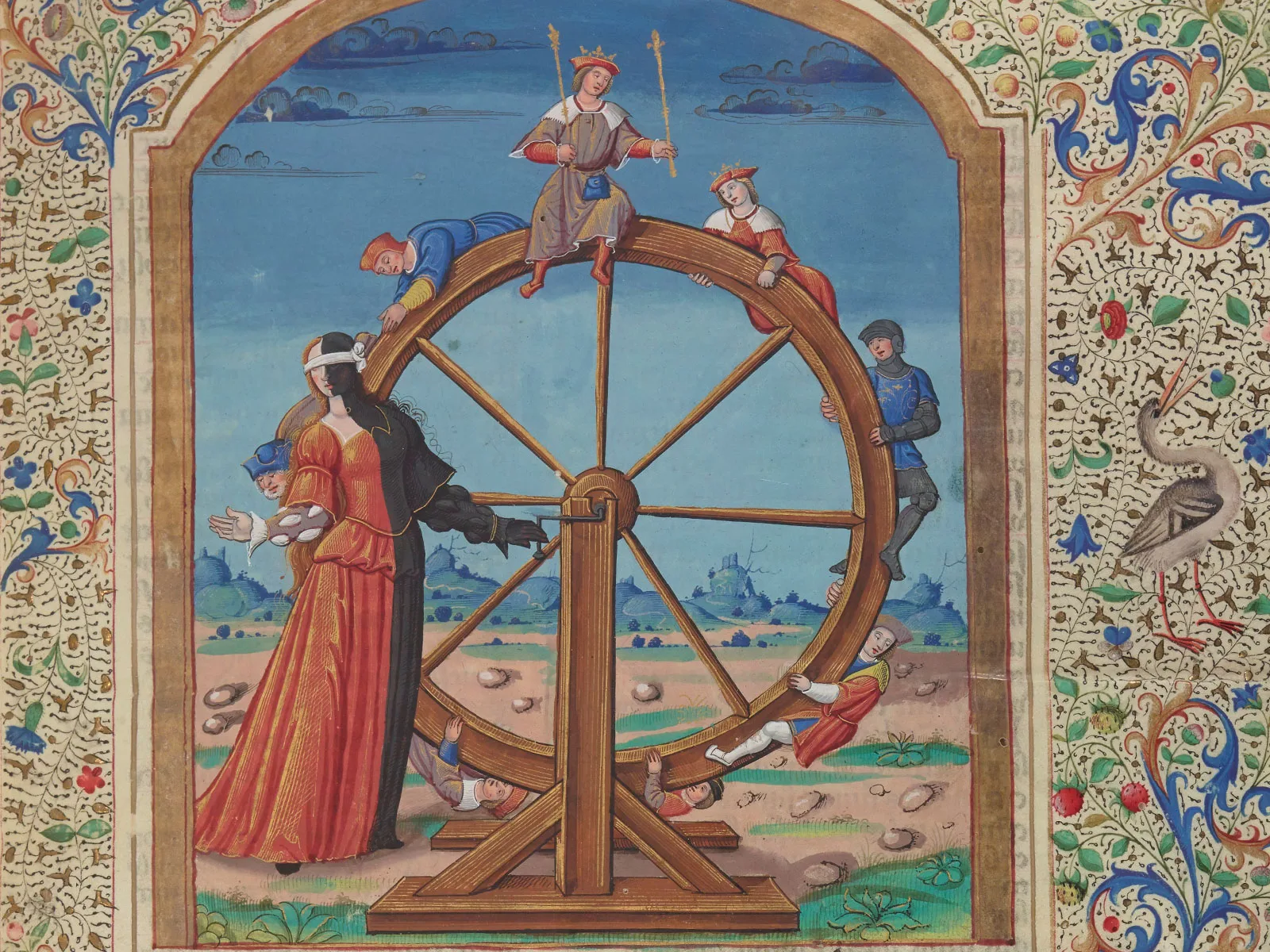

Medieval song manuscripts are seldom illuminated. The Carmina Burana is an exception. The codex contains colourful initials as well as plentiful drawings and paintings. And, unlike the wheel of fortune in Basel, where neither Fortuna nor rulers are depicted, here the crowned goddess of fate is seated demonstratively at the centre of the rota fortunae, surrounded only by kings. While the monarch at the top proclaims: regno – I reign, the second king’s crown falls from his head as he tumbles: regnavi – I reigned; the one at the bottom laments: sum sine regno – I have no kingdom, whereas the ascending king triumphantly states: regnabo – I will reign. YouTube / Bavarian State Library

A kingdom for a pear

O Melancholia

![Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375), De casibus virorum illustrium – On the Fates of Famous Men [and women], 1467 Paris edition.](https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/app/uploads/08-wikimedia-fortune-wheel-15c-french.webp)

Who counts the wheels, names the names

![Illustration from John Lydgate, The quene [queen] of Fortune, a moralising tale relating the history of Troy, written from 1412 to 1420.](https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/app/uploads/john-lydgate-the-quene-of-fortune.webp)

A giant wheel as a wheel of fortune

Happiness framed globally

The song "Leg dein Ohr auf die Schiene der Geschichte" of the music group "Freundeskreis". YouTube