The theatre that stood up to fascism

Just a few months after Adolf Hitler came to power, Schauspielhaus Zurich theatre began to evolve into a bastion against racial fanaticism and antisemitism.

Rieser was the beneficiary of the “staff restructuring” ordered by Joseph Goebbels in Germany’s theatres, as he capitalised on the situation and attracted a number of backstage luminaries. Gasbarra, who concluded a contract with Rieser, travelled on to Zurich to rejoin many of his former Berlin contemporaries, who had scattered like a herd of sheep after a wolf had broken into their pen.

Illustrious names, including Kurt Horwitz, Ernst Ginsberg, Wolfgang Langhoff, Therese Giehse and stage designer Teo Otto thrust Schauspielhaus Zurich from the provincial shadows to the forefront of German-speaking theatre in the space of a few months. The highly talented Leopold Lindtberg (formerly Leopold Lemberger) was the feather in the theatre’s proverbial cap: his productions caused a furore in Rieser’s appealing, but basically apolitical theatre.

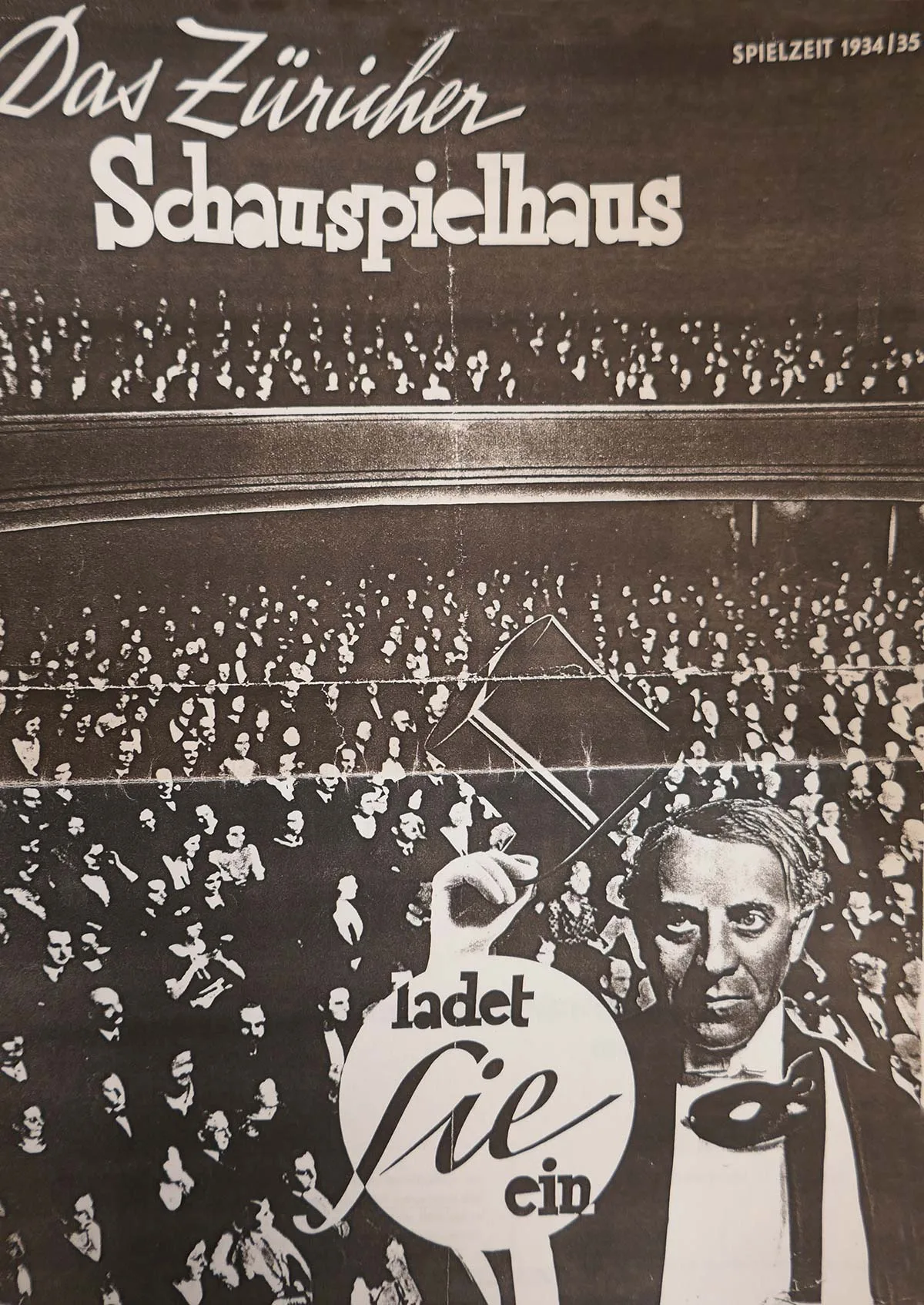

The programme for 1934/35 with such classics as the obligatory William Tell by Schiller, the successful Katharina Knie by Carl Zuckmayer, light comedies and bourgeois dramas grew by more than 20 premieres per season. One play stood out: Professor Mamlock – or Professor Mannheim in Zurich, by doctor and dramatist Friedrich Wolf addresses the antisemitism prevalent at the time. The leading character, Jewish doctor Professor Hans Mamlock, a dedicated democrat, is unable to bear the growing repression of the Jews and in his despair, commits suicide. “A drama from the Germany of today,” as the author described it.

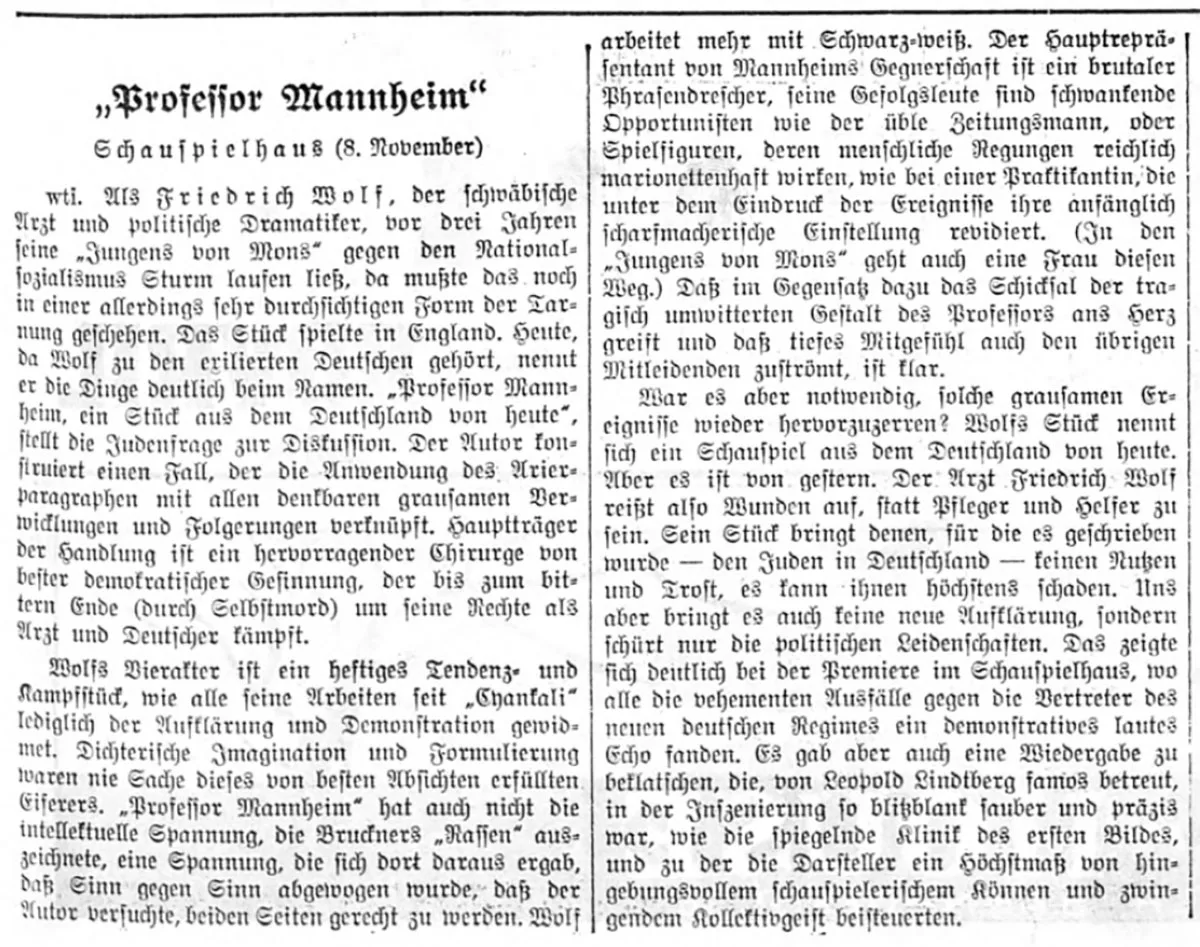

Ferdinand Rieser showed courage in going ahead with the play despite warnings from his pro-Germany friends and gave the green light to a play that called for resistance to racial fanaticism and antisemitism. The Zurich newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ), mindful of not provoking their neighbours across the border, wrote: “Was it necessary to revisit such gruesome events? […] Wolf’s play brings no benefit or consolation to those for whom it was written – the Jews in Germany – it may even prove detrimental to them. Nor does it tell us anything new, it just stirs up a political hornets’ nest. That was evident at the premiere, where all the vehement outbursts against the new German regime found a resounding echo” and concluded that addressing the “specifically German and thorny issue of the Jewish question” was inappropriate and a “forceful demand to take sides”.

On 27 November 1934, the Basler Nationalzeitung commented: “From the line of armed police outside the building in steel helmets and armed with rifles, it was obvious to the Zurich theatregoers who attended Professor Mannheim on Monday that they weren’t going to just any play. The police vans were parked in front of the theatre, followed shortly after by big prison vans. The demonstrators were unmoved and responded with foul language and anti-police chants. The riot led to 108 arrests including that of Dr Henne, leader of the [Swiss] National Front.”

Professor Mannheim marked the start of the Zurich theatre’s campaign against fascism and the venue hosted three premieres written by Bertold Brecht between 1941 and1943. Nonetheless, the expatriate contingent had a hard time in Switzerland. Felix Gasbarra recalled, “the immigration police were very distrustful, even dismissive, of all immigrants and did their best to prevent immigrants from staying in the country”. And NZZ feature editor, Eduard Korrodi, never missed an opportunity to denounce “the blatant emergence of political immigrants in our country”.