Face to face: a history of portrait painting

Thanks to digital technology, the creation and sharing of portraits is now popular, cheap, and almost obligatory. Before the advent of photography, this task was fulfilled by portrait painting. We take a look at its origins and how it evolved.

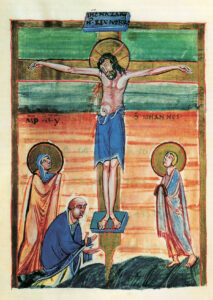

From mummies to donors

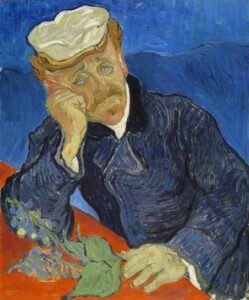

Moving away from religious themes

The self-portrait takes hold

The golden age of portrait painting

Continuity of portrait painting in the age of photography