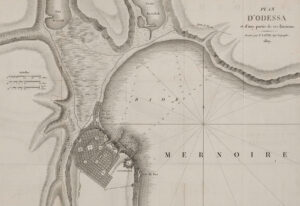

Ticino architects in Odesa

Some of the most important buildings in the Black Sea city were designed by architects from Ticino. From its founding in 1794, the work of these Swiss architects has given the city a Mediterranean flair.

Some of the most important buildings in the Black Sea city were designed by architects from Ticino. From its founding in 1794, the work of these Swiss architects has given the city a Mediterranean flair.