Face to face: a history of portrait painting

Thanks to digital technology, the creation and sharing of portraits is now popular, cheap, and almost obligatory. Before the advent of photography, this task was fulfilled by portrait painting. We take a look at its origins and how it evolved.

From mummies to donors

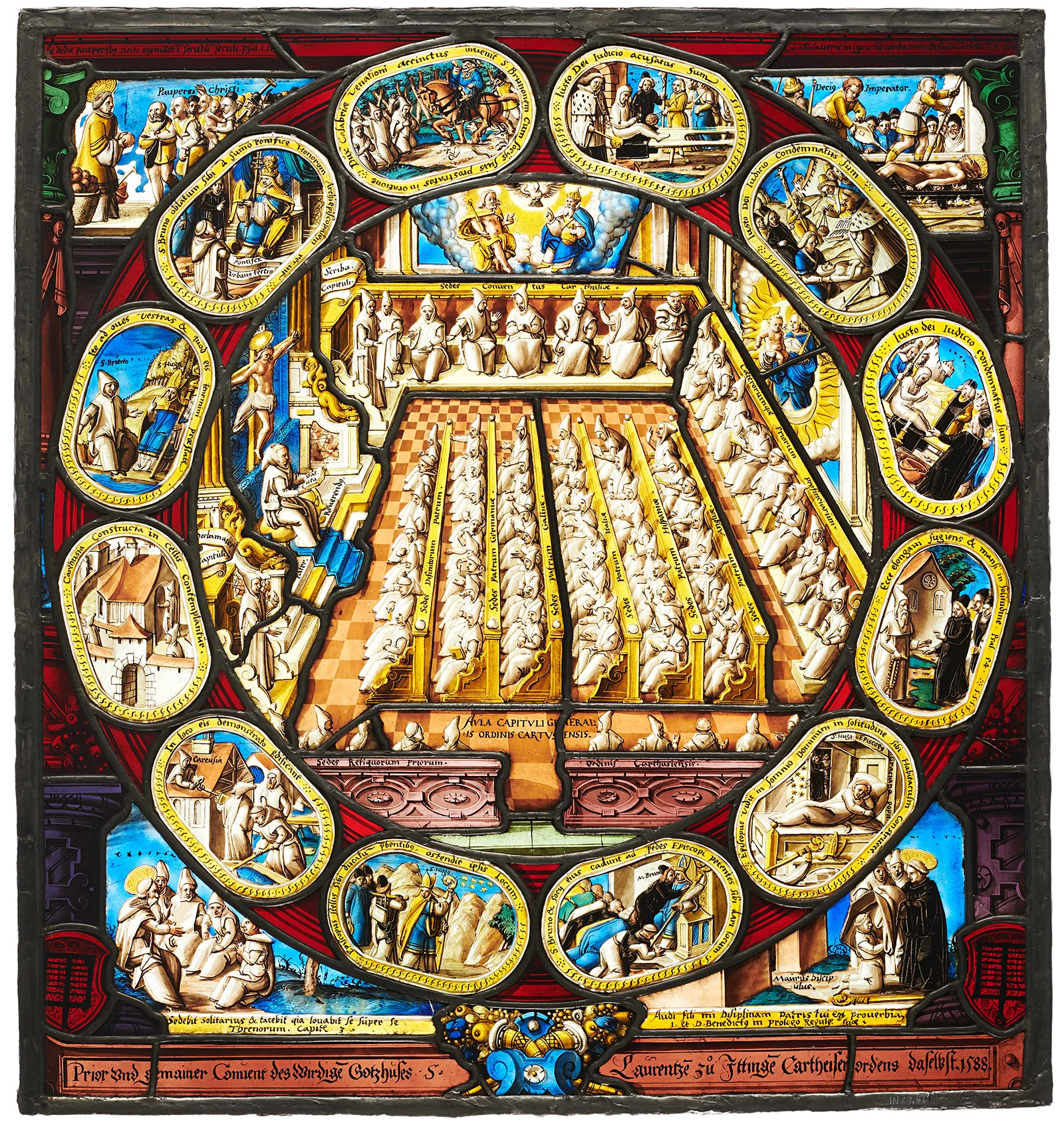

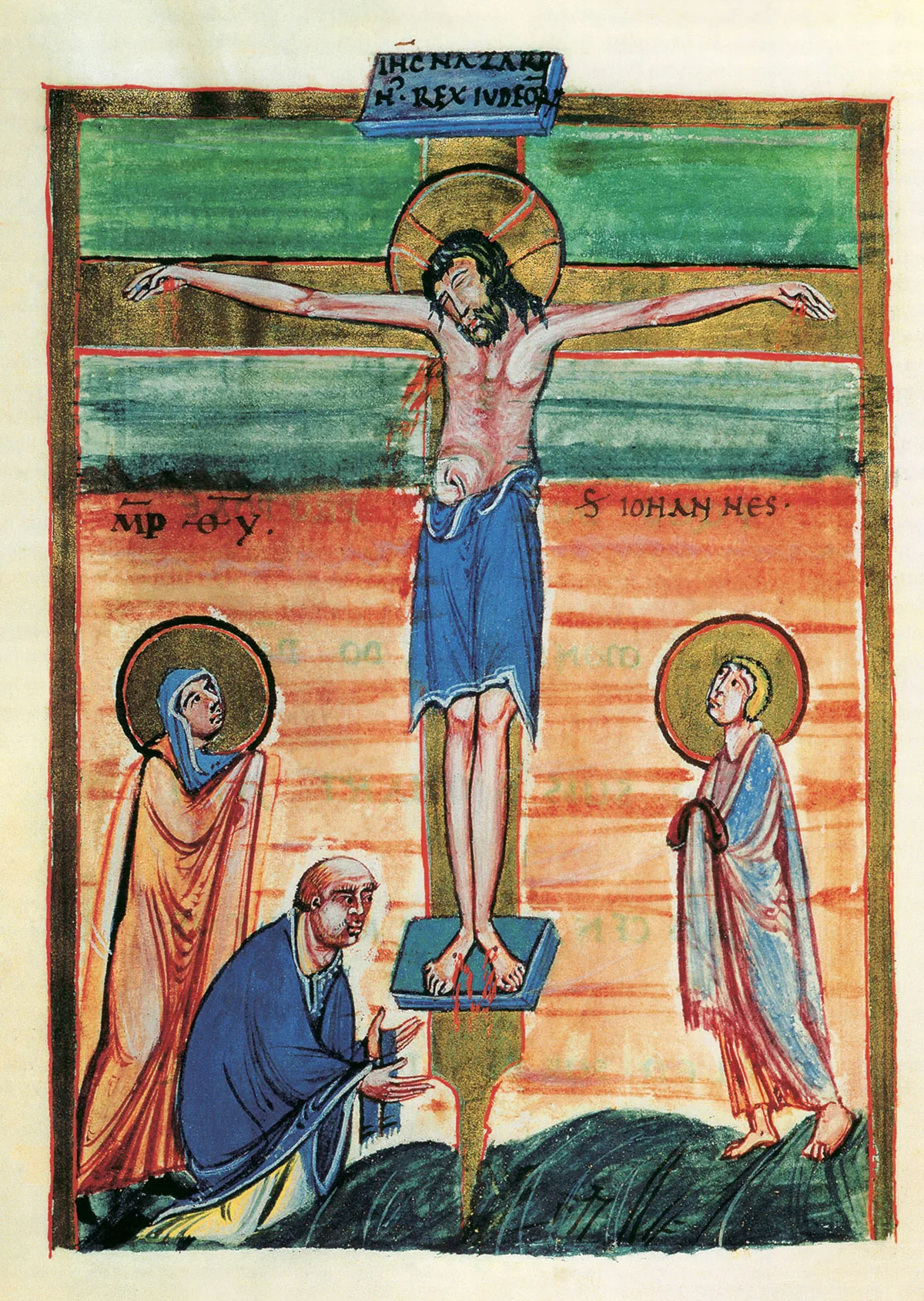

There are exceptions, however, such as the dedication miniatures in illuminated manuscripts, which depicted the illuminator handing over their work to the donor or patron, or showed the donor or patron presenting the book they had commissioned to a church. Often, the donor is shown kneeling in prayer, flanked by saints or humbly integrated into a biblical scene. This was because portraying a mortal was only tolerated in a religious context.

Moving away from religious themes

Meanwhile, prominent early Netherlandish painters of the 15th century included Robert Campin, Rogier van der Weyden and Jan van Eyck. Van Eyck painted the ‘Arnolfini Portrait’, which is one of the most important full-length double portraits in the history of art. The intriguing painting, which is full of symbolism, is believed to depict the merchant Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife Giovanna Cenami. It was long thought to depict a wedding or engagement, but art historians now think it is neither of these. The mirror in the centre of the painting shows the reflections of two other figures in the room. The inscription ‘Johannes de Eyck fuit hic 1434’ (‘Jan van Eyck was here, 1434’) has given rise to speculation that one of the figures in the mirror is in fact Jan van Eyck, or that the painting may be a self-portrait of the painter with his wife Margarethe – the wooden figure on the bedstead shows the saint of the same name. As the best-paid ‘valet de chambre’ of the Duke of Burgundy, van Eyck was wealthy enough to be able to afford the furnishings and clothing featured in the painting. As one of the first painters to actually sign his works, he was not short of self-confidence either.

The self-portrait takes hold

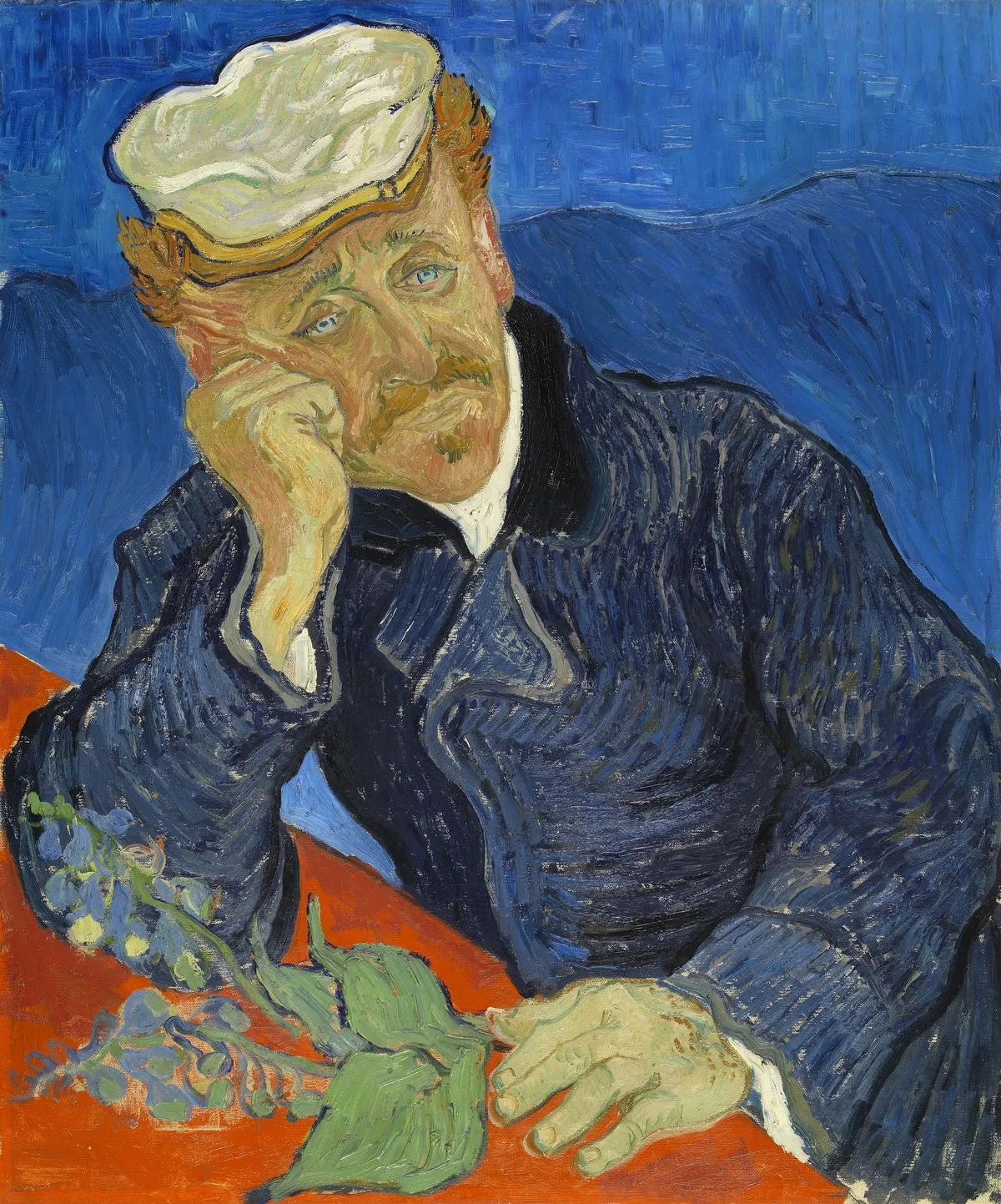

Artists also used the self-portrait as a practical testing ground and for study purposes. Rembrandt was particularly celebrated for doing this in the 17th century. Very few artists before Rembrandt created so many self-portraits with different facial expressions, grimaces and gestures.

The golden age of portrait painting

Portraits of the nobility were mainly produced for prestige purposes, which is why they were often painted against imposing or dramatic backdrops or in sumptuous interiors. The idea was to elevate the sitter in an idealised, distant and even lofty manner, in order to prepare them for the glorious afterlife. The external depiction of the person was usually interlaced with the staging of power, success, status, wealth and strength. For women, beauty was another factor, for which painters were sometimes willing to bend the rules. In addition to regalia such as crowns and sceptres, medals and military ‘props’ such as helmet, armour and sword were popular visual cues. While noble attire made of silk, velvet or lace was a popular status symbol in portraits of both sexes, women also wore valuable accessories for this purpose.

One such commission entrusted to Hans Holbein the Younger is an example of an unsuccessful venture in this regard. Holbein, who was born in Augsburg and worked in Basel until 1532, made a name for himself in England painting portraits of notable figures including Erasmus of Rotterdam and Thomas More, before rising to become court painter to Henry VIII in 1536. After the death of his third wife, Henry VIII was looking for a bride again, so sent Holbein to the Continent to paint portraits of several potential marriage candidates who, needless to say, also had to be attractive. They included the daughters of John III, Duke of Cleves in Düsseldorf. The King was so taken with the portrait of one of them, Anne of Cleves, that he married her without even meeting her in person. But when she arrived in England, he was not at all impressed with his new bride. Henry VIII’s fourth marriage was therefore annulled a short time later on the grounds that it had never been consummated.

Continuity of portrait painting in the age of photography

From the 1960s, the advent of photorealism brought an artistic movement to painting that ran completely counter to abstraction: through painted portraits of hyperrealistic clarity – such as those by Chuck Close, Gerhard Richter and Franz Gertsch – you could say that painting finally got one up on photography.