The different fates of Switzerland’s dialects

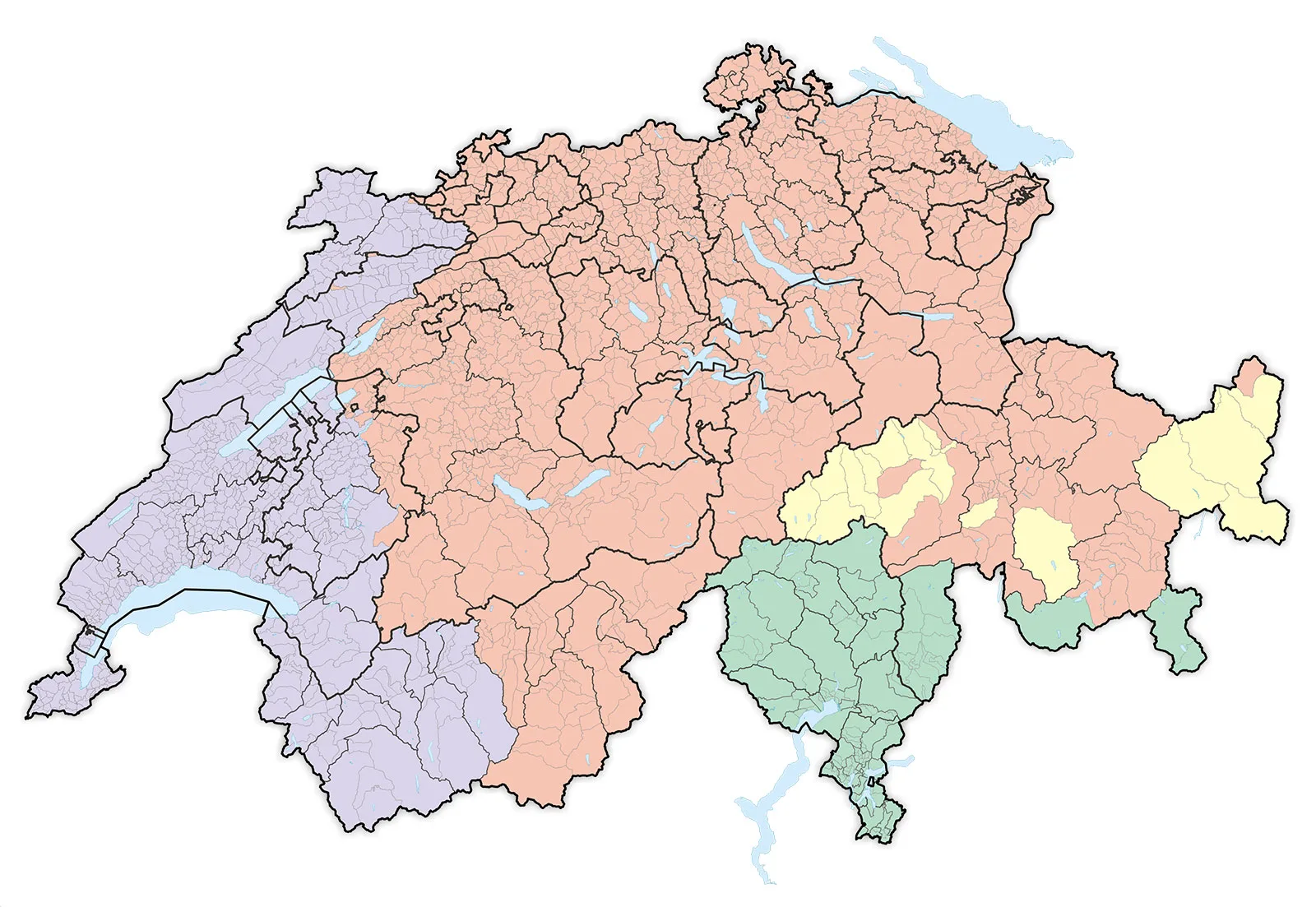

Dialects play different roles in Switzerland’s language regions: in German-speaking Switzerland they dominate everyday life, while in French-speaking Switzerland they have virtually disappeared, and in Italian-speaking Switzerland they are only spoken with close friends and family. The reasons behind these differences can be found in history.

‘Fläckehans’ aka Johann Weisshaupt from Eggerstanden in Appenzell Innerrhoden, tells a joke in Appenzell dialect. Segment from “Schweiz aktuell unterwägs’ of 24.08.1990. SRF

Traditional herdsmen’s songs are common in Switzerland’s rural regions, from the Bernese Oberland and Appenzell to Jura and Vaud. One of the most famous is the ‘Ranz des vaches’ from Greyerzerland. The text is written is Fribourg patois. RTS/YouTube

In 1547, Jacques Gruet from Geneva protested against the growing influence of French priests. He put up a threatening note in patois on the walls of Saint-Pierre Cathedral. The first line says “Gro panfar, te et to compagnon gagneria miot de vot queysi”, which means “Hey fatso, you and your associates should keep your mouths shut!” Recording of Jacques Gruet’s pamphlet of 1547, read by Olivier Frutiger, 2023. Archives d'Etat de Genève

00.00

Vüna par ün: Don Francesco Alberti speaking Ticino dialect from Bedigliora, 1939. © Phonogram Archives of the University of Zurich