The Ticinese and the Australian Gold Rush

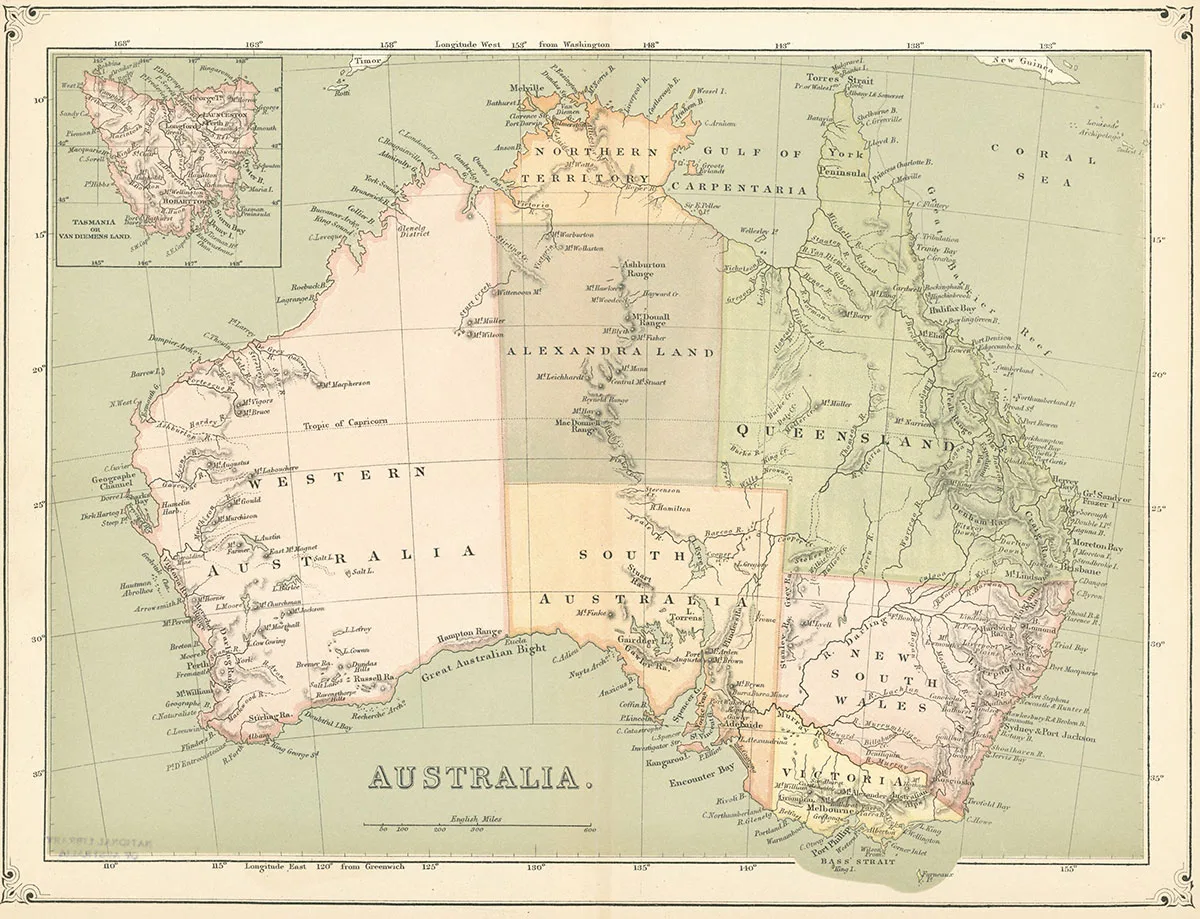

In August 1854, Giovanni Antonio Palla from Cevio and Tommaso Pozzi from Coglio returned to Ticino after securing a fortune through mining in the southeastern Australian state of Victoria. News of their arrival spread like a wildfire, spurring a wave of migration. Around 2000 Ticinese participated in the Australian Gold Rush of the 1850s, and left an indelible imprint upon the country.

…We've golden soil and wealth for toil; Our home is girt by sea; Our land abounds in nature's gifts; Of beauty rich and rare…

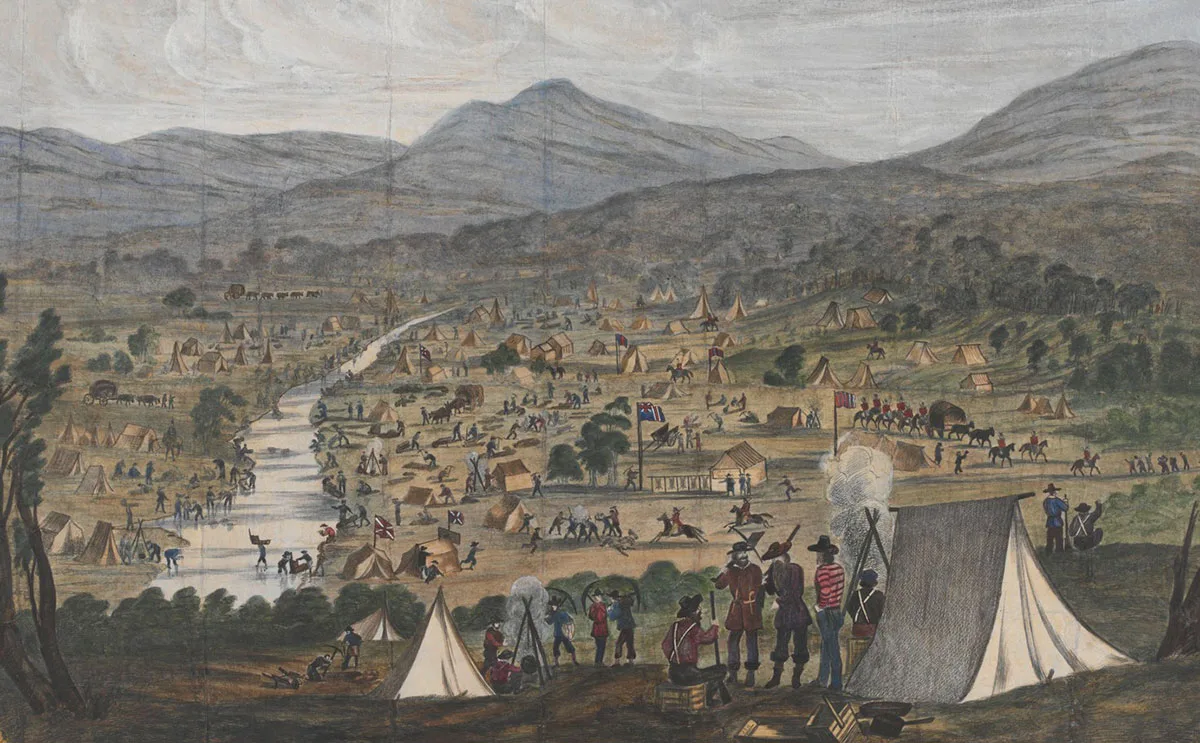

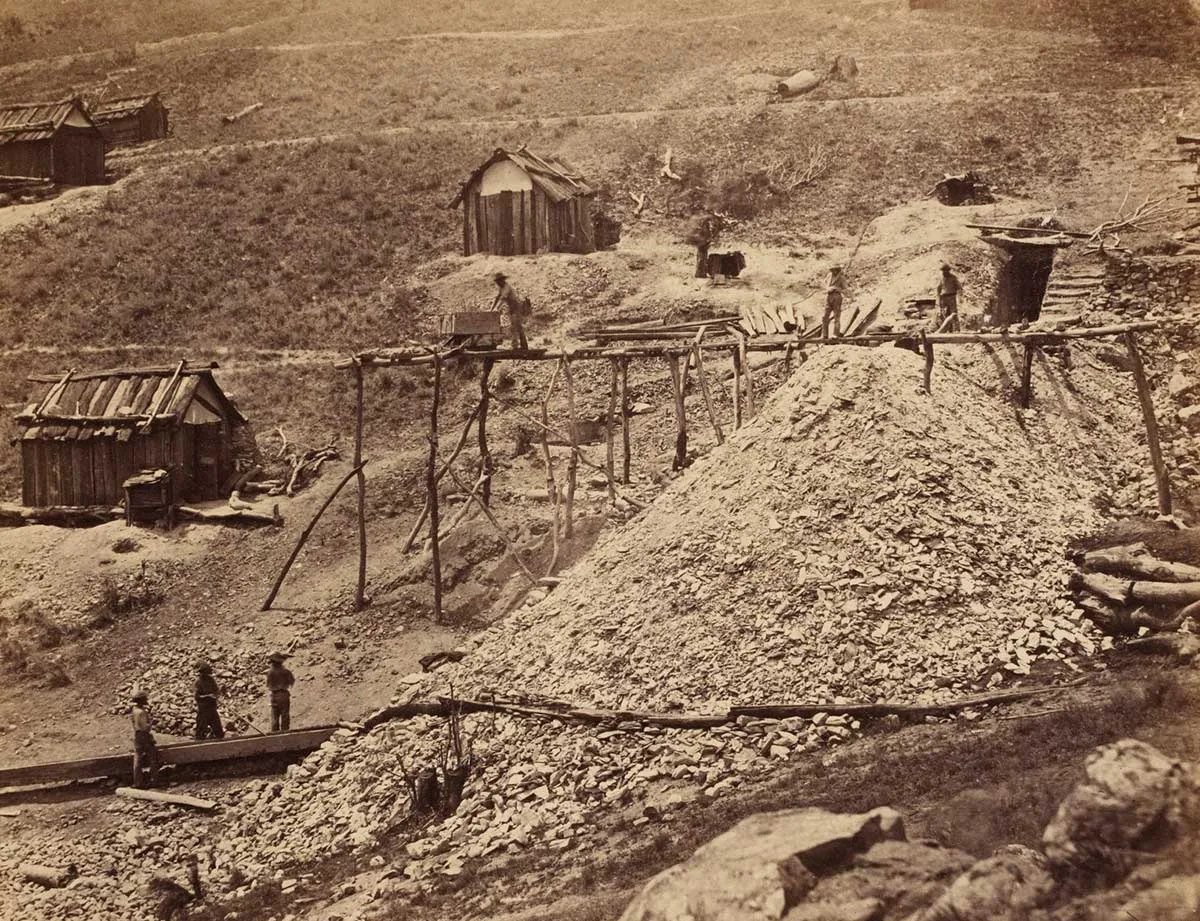

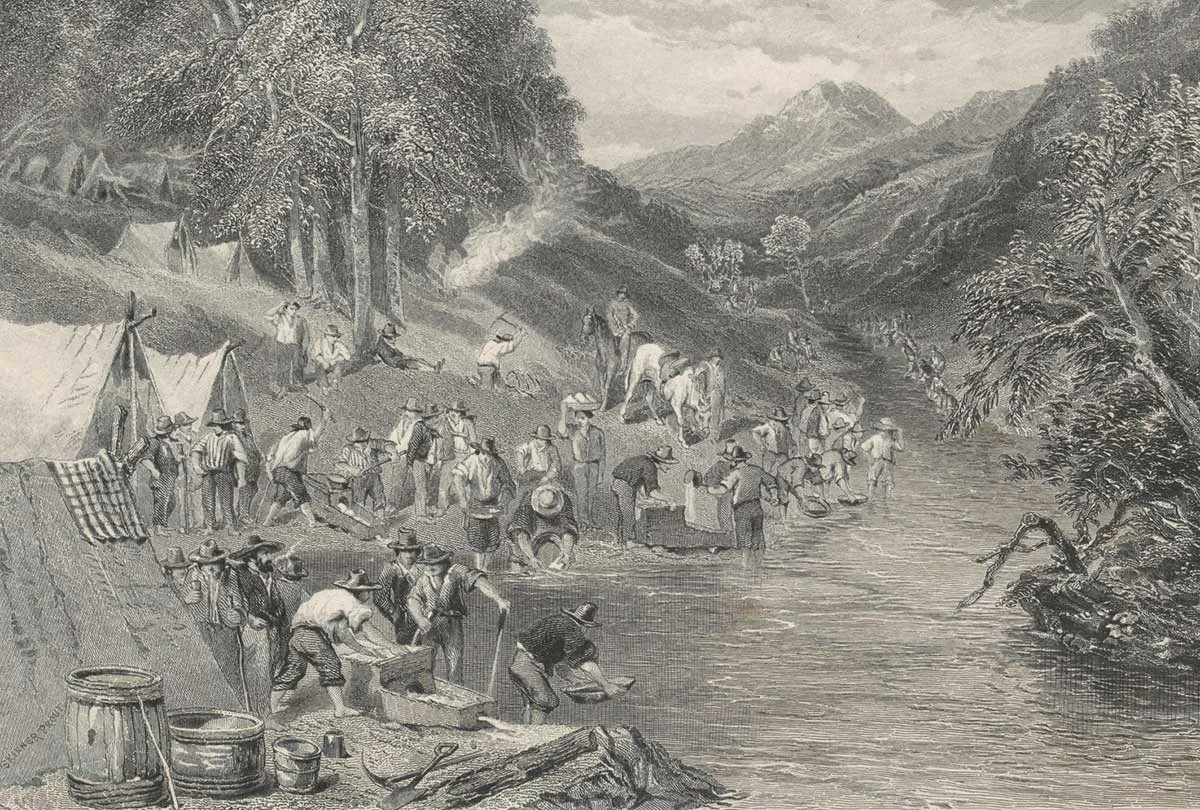

Working in the Fields of Gold

I could not sleep that night, nor for many nights after in that tent. I had never come across such a thing. I was cold and the worst of it was the hunger, the number of fleas and lice that crawled all over me, and the mice at my neck and ears all night long.

Impact and Legacy