Europe’s highest open-air lift

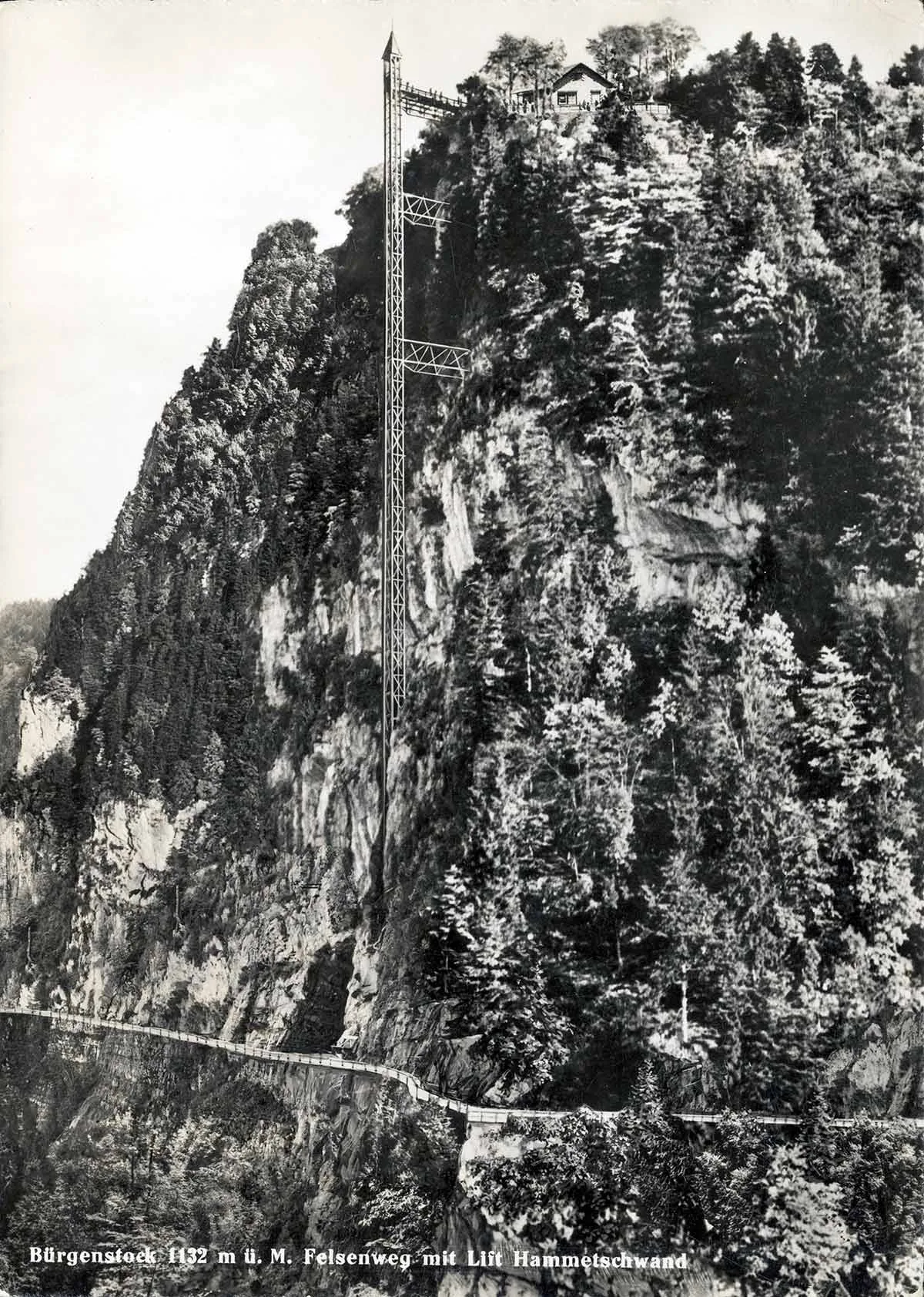

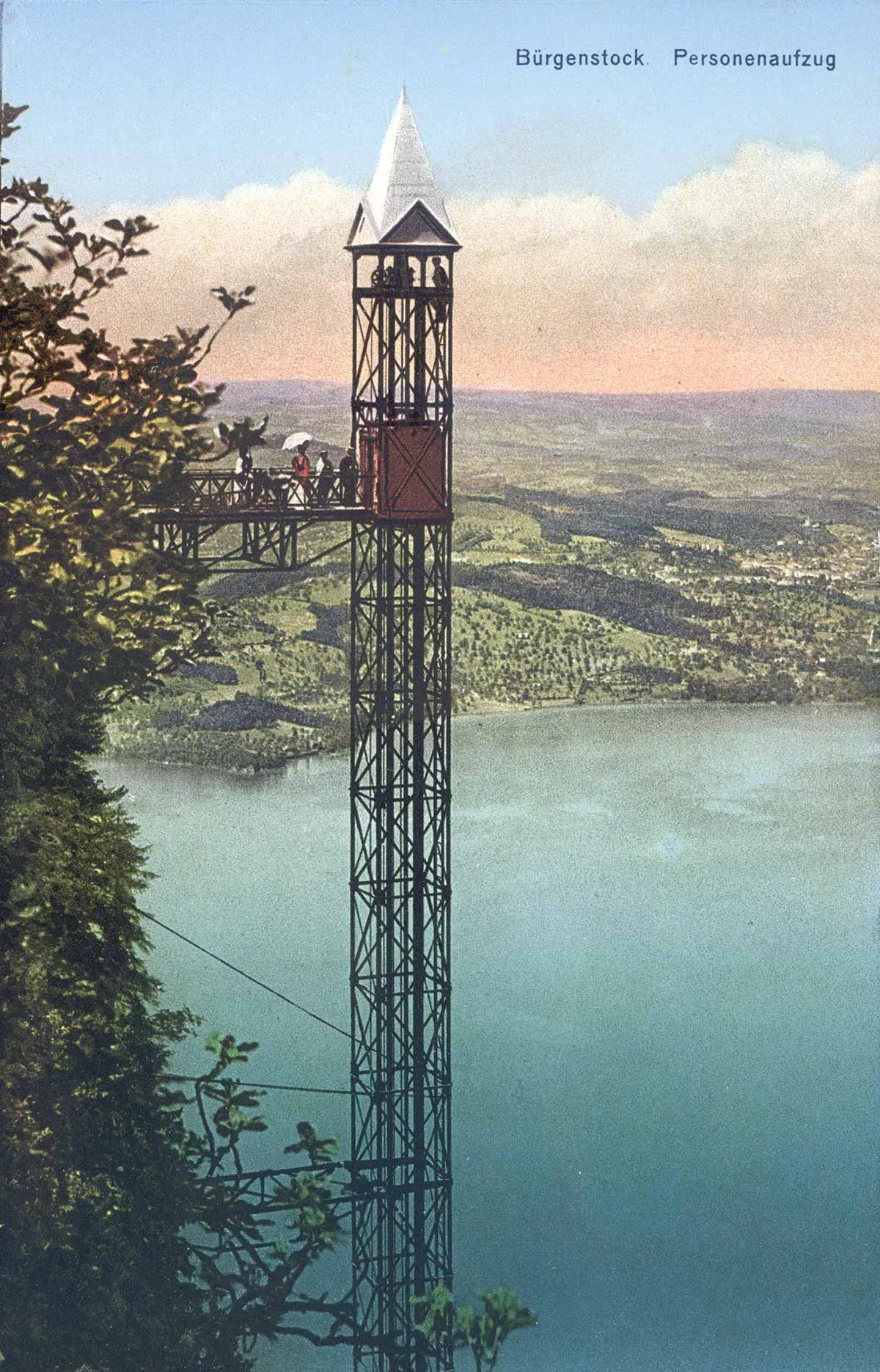

The Bürgenstock has always known how to skilfully attract attention, as it did back in 1905 for example with the spectacular Hammetschwand lift – a marvel of Swiss engineering. Over the years, the lift has been a source of both admiration and rumour.

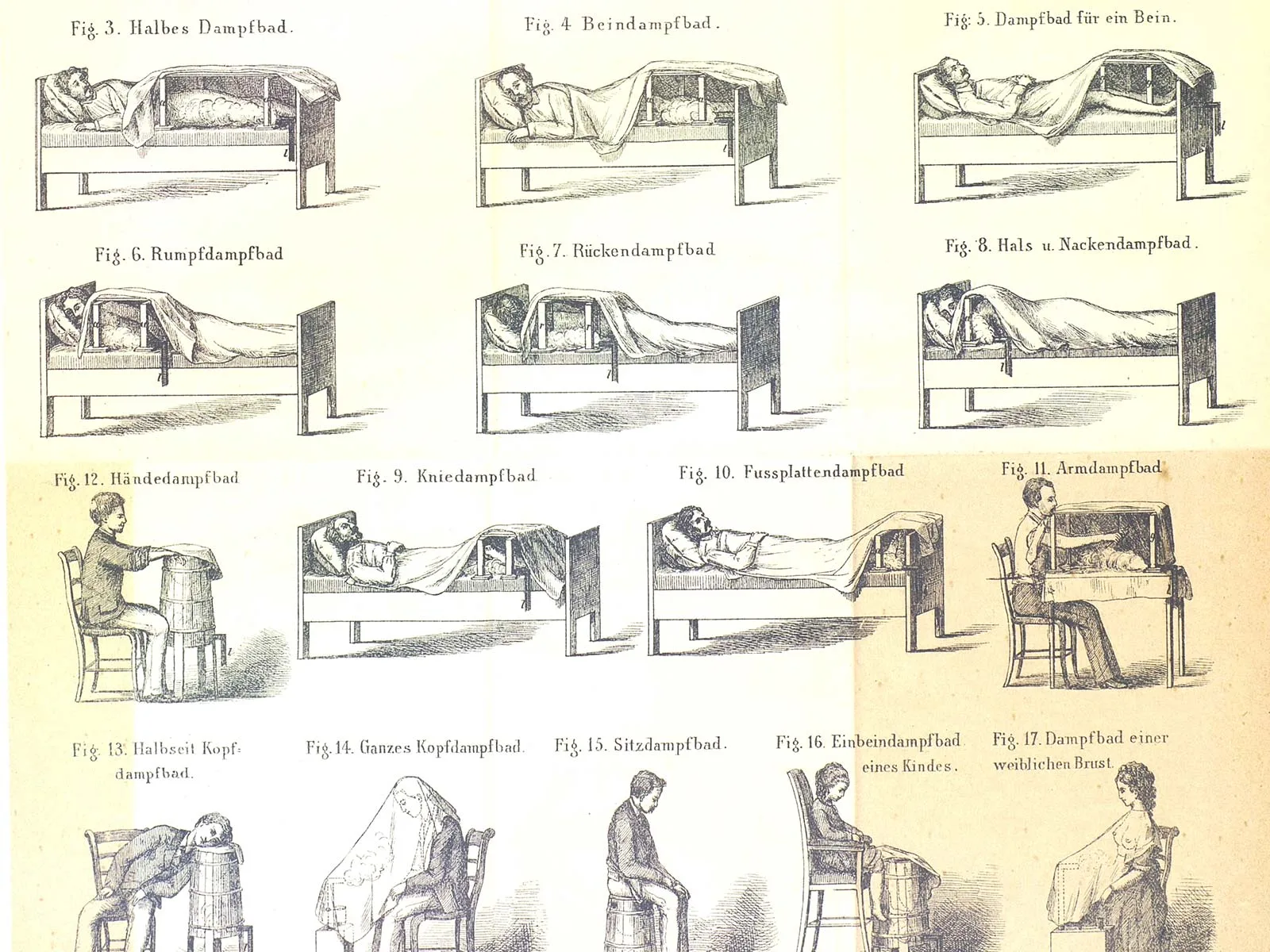

A risky construction project

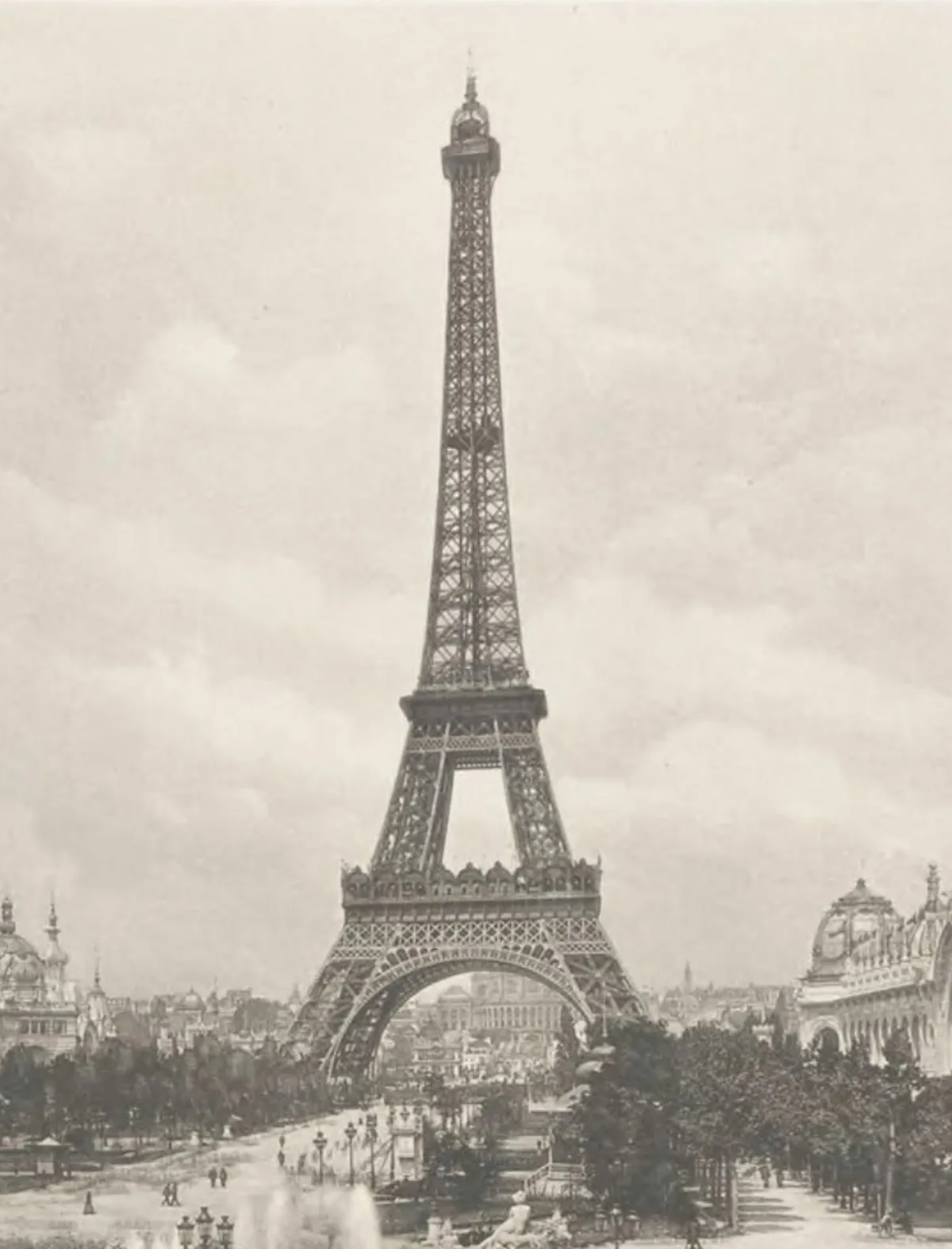

Switzerland’s own ‘Eiffel Tower’

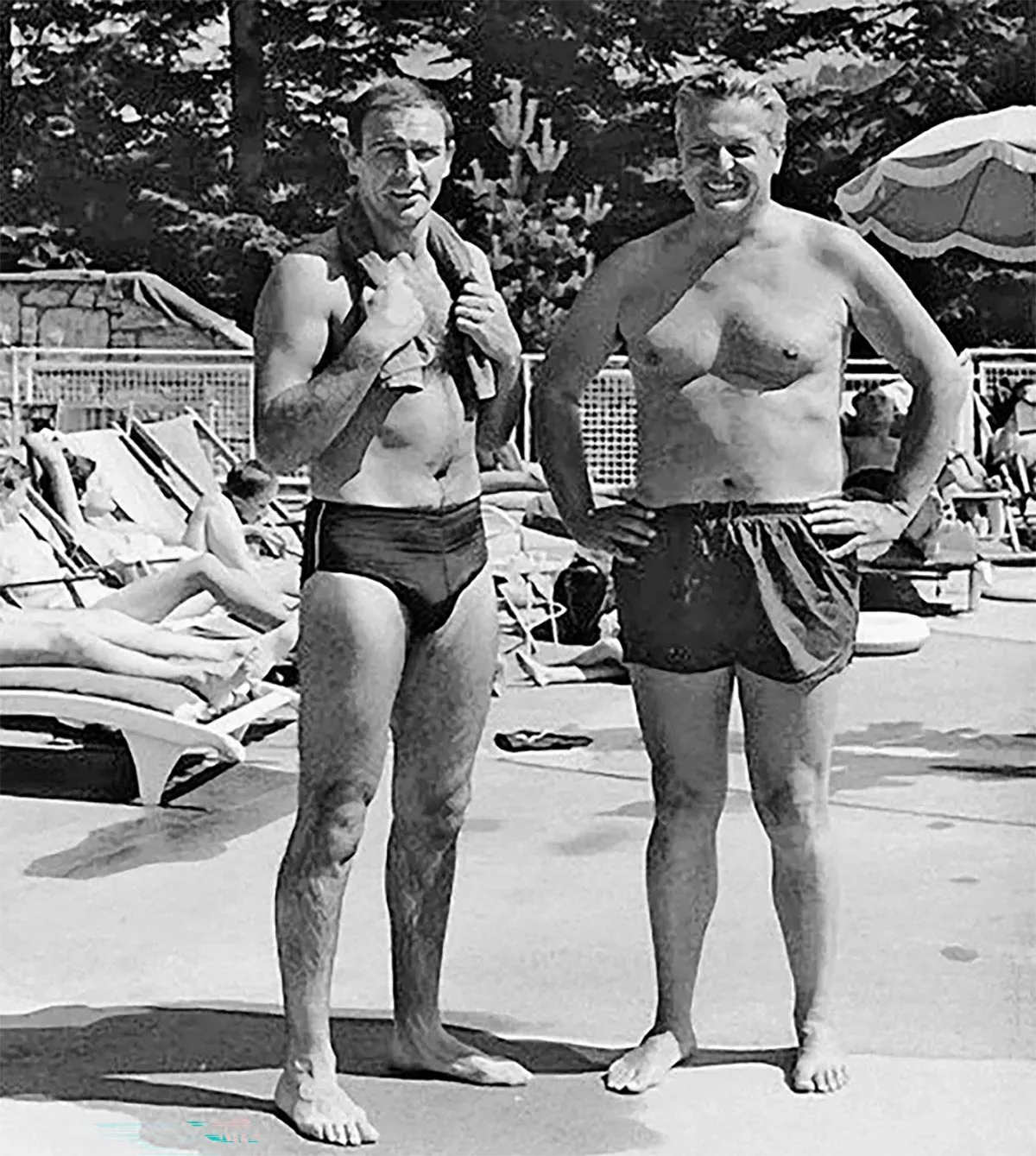

The James Bond rumour