Knocked off his pedestal

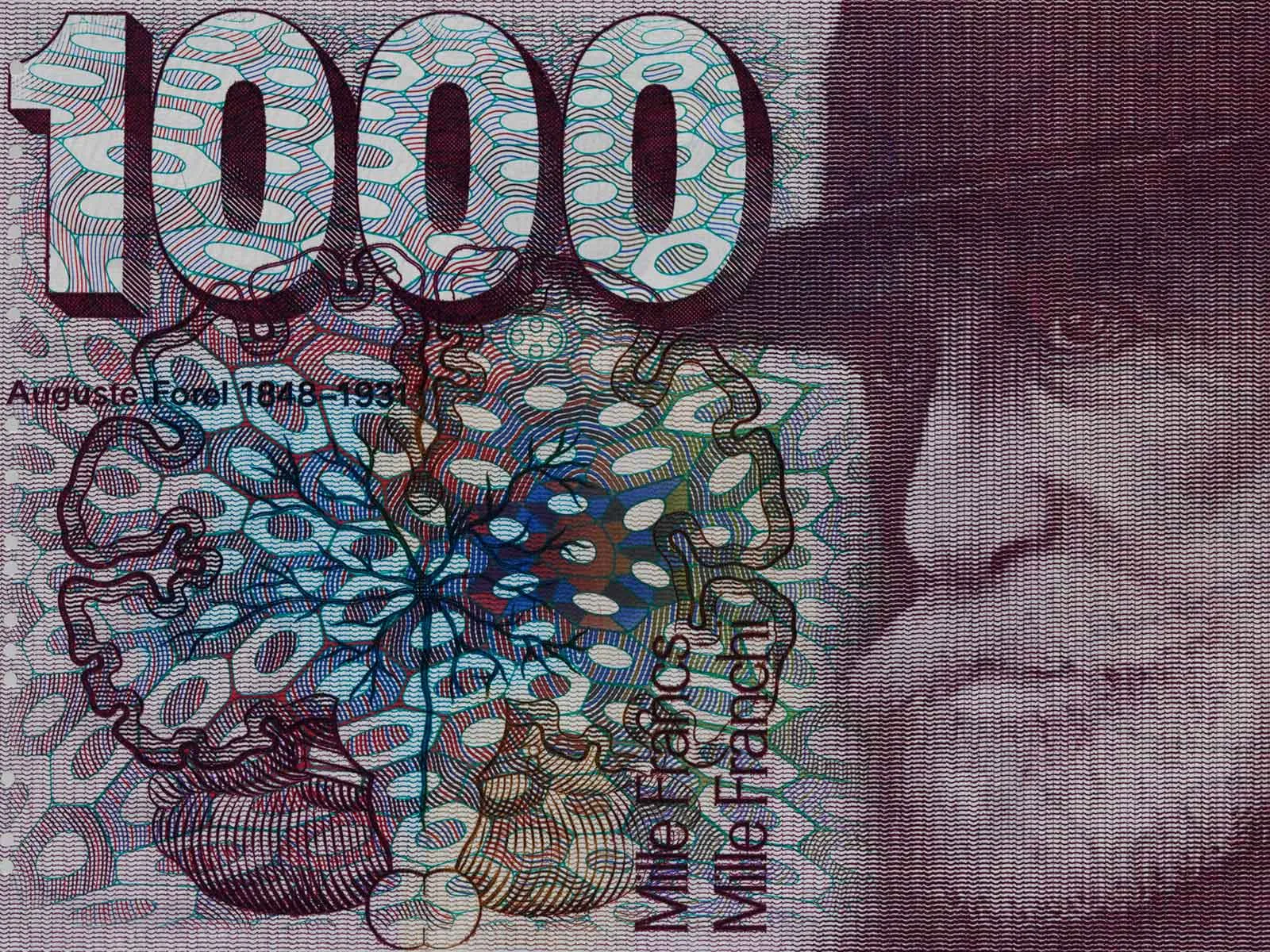

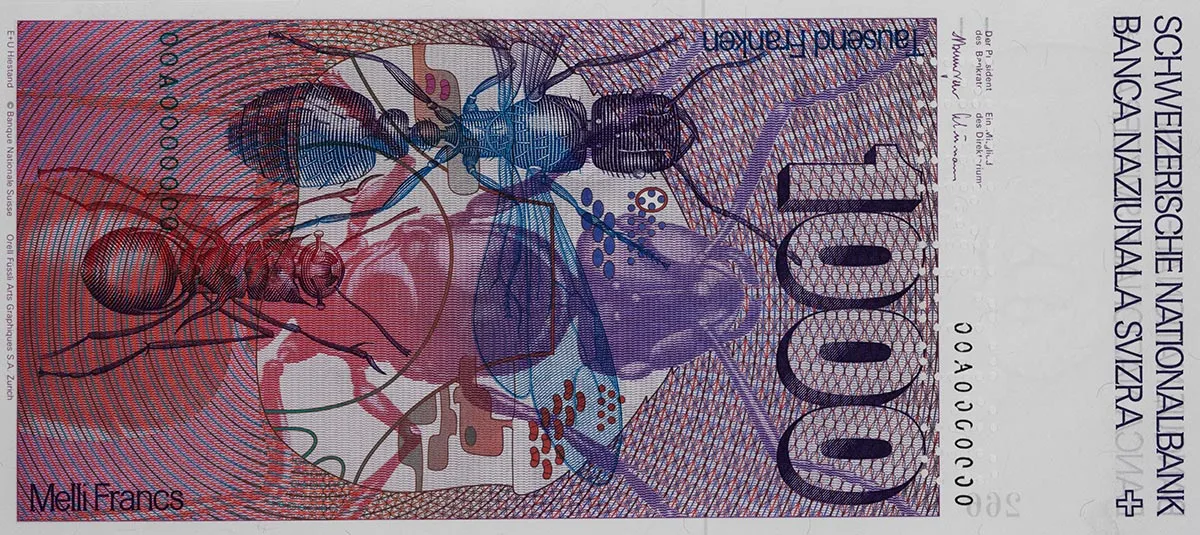

In the last-but-one series of Swiss banknotes, the thousand-franc note depicted Auguste Forel as a wise researcher turning his alert gaze on the world, as an icon of science and Helvetic national symbol. But this stylised heroic image failed to stand up to closer investigation. A story illustrating the pitfalls of the culture of commemoration.

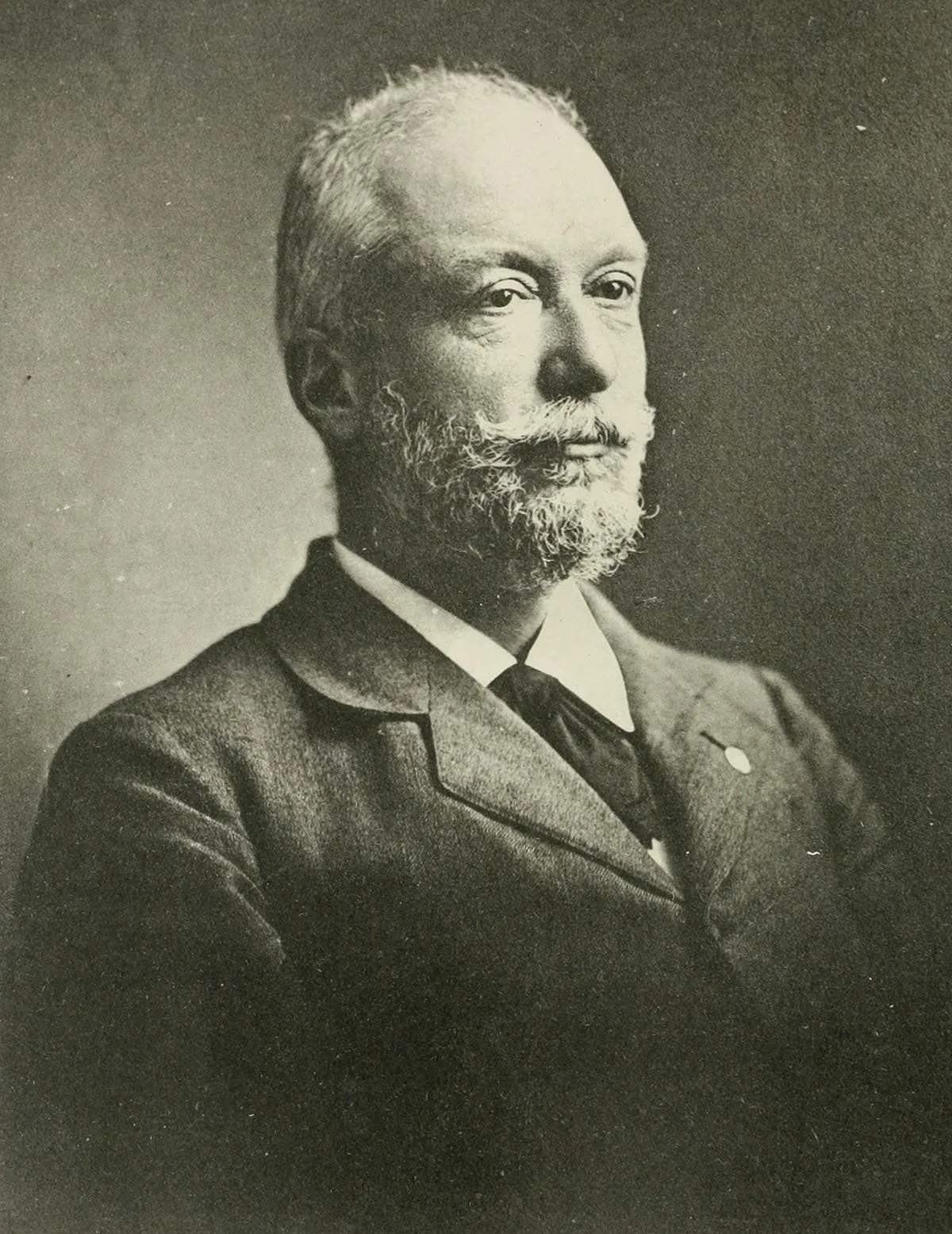

Forel’s activities reflected his wide-ranging interests. In numerous publications, he tackled a broad spectrum of topics ranging from neuroanatomy to hypnosis, penal reform, alcoholism, sexual mores, genetics, criminal psychology, pacifism and social philosophy through to questions of international policy. He was vehement in his support for full gender equality, free access to contraceptives and the legal recognition of cohabitation, as well as in his opposition to discrimination of homosexuals. His book “The sexual question” became a long-running best seller, was translated into 16 languages and had a lasting influence on 20th-century attitudes to sexuality. Forel also gained fame for his important research on insects, especially ants and termites. He went on extensive research trips throughout Europe and overseas that enabled him to describe some 3,500 species. His two main works in this field are still considered seminal classics to this day.

The Social Darwinist

This Social Darwinism became the standard ideology of the bourgeois era of high capitalism, which attempted to justify its urge for expansion, its aggressive colonial policy and the negative impact of the concentration of economic power by framing them in terms of an imperative supposedly dictated by the laws of nature. Without questioning or even condoning these objectives (for Forel, a Social Democrat from 1916, the capitalist system was “a disgusting, pestilential swamp”), he adopted large parts of the Social Darwinist mindset and worked on their advancement, proceeding from the basic assumption that, as in the wild, social and historical processes in human society were primarily determined by biological dispositions.

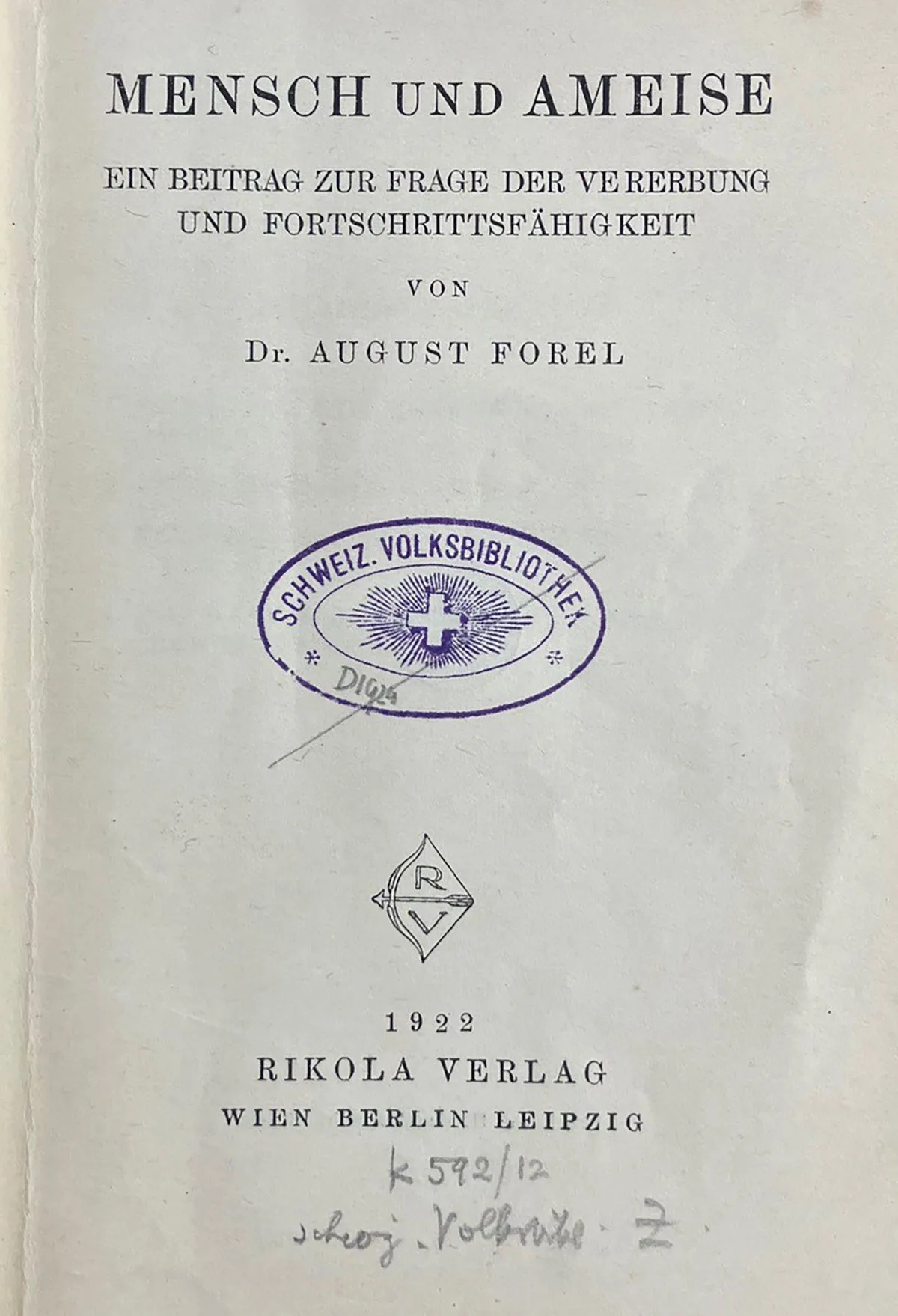

As a doctor and psychiatrist, Forel believed that "man’s hereditary nature, deep-rooted in his brain, makes him an egotistic, individualistic, fierce, domineering, tyrannical, jealous, passionate and revengeful being”. But as a myrmecologist, Forel asserted: “Truly, I believe that the social instincts gradually accumulated and established in an ant are much wiser than those that a Linnean homo sapiens can acquire in spite of all the knowledge and traditions passed down to him and despite the best education.” Forel rated the “socialism” of an ant colony as “far superior” to all human social orders and in 1922, synthesising his two main areas of work – psychiatry and entomology – asked himself: “What can we do, then, to grow nearer to the ants and yet remain men?”

Race hygiene, eugenics, euthanasia

The physician and former director of the Burghölzli clinic saw modern healthcare practices as having a highly deleterious effect on the future of the human race: “As doctors it is our sad duty to preserve the life of idiots, degenerates, born criminals and the insane as long as possible.” And, taking this thought one step further, he considered the question “of whether it is not the best and most humane way to eradicate the most disgusting specimens of the human brain (criminals and the mentally ill) by painless death” to be worthy of consideration. He had himself ordered the use of sterilisation and castration at Burghölzli.

Sinister side – long ignored and hushed up

In 1988, when the exhibition was held again at the University of Bern, protests were staged. But it would not be until some years later, in 1999, that a book by historian and journalist Willi Wottreng on Forel and fellow psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler’s attempts “to save the human race” would reach a wider audience.

“From memorial to historical bind”

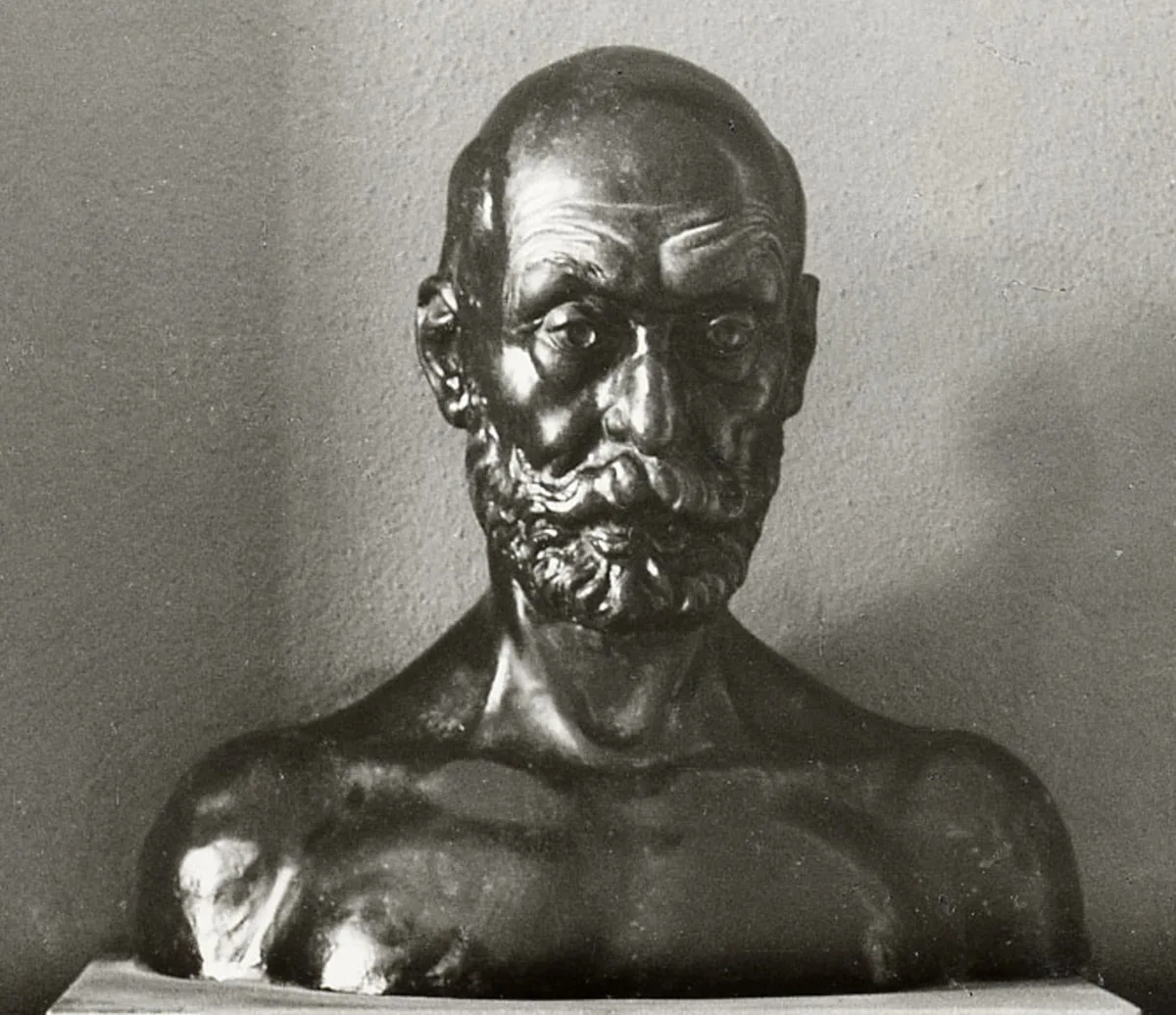

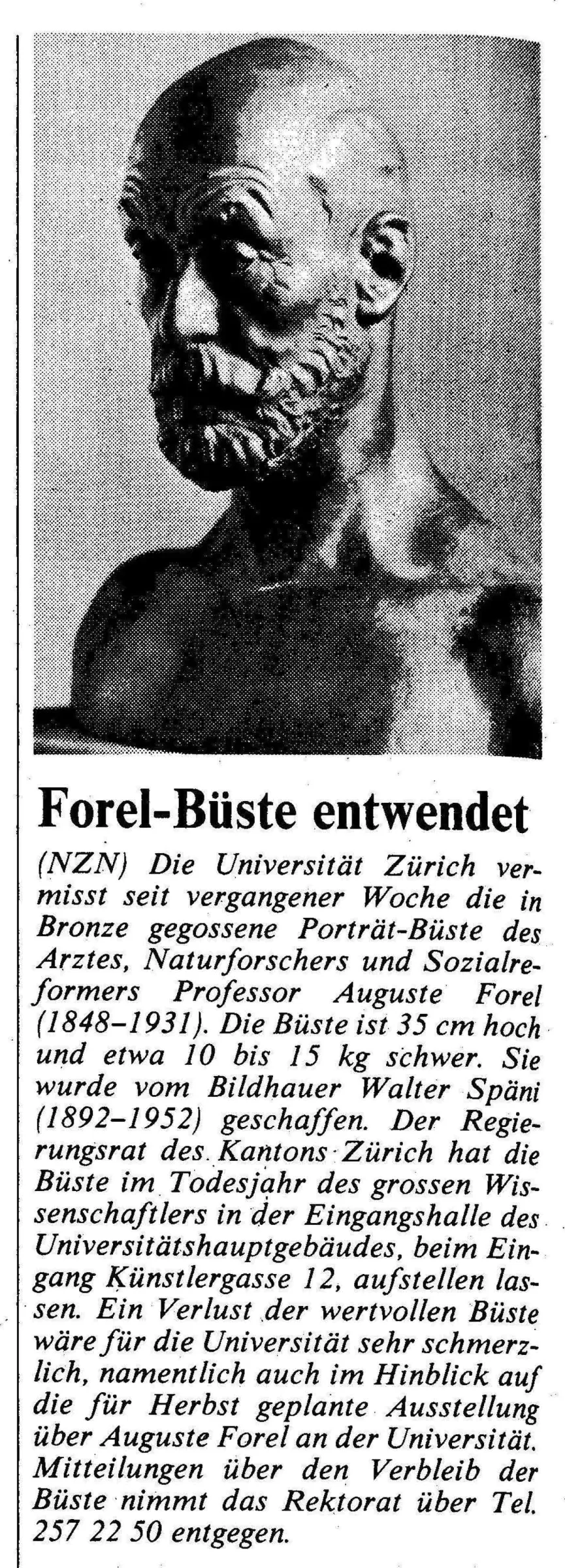

In 2003, an article appeared in the Zürcher Studierendenzeitung entitled: “Und täglich grüsst der Eugeniker” [The eugenicist greets us every day]. Irritated after reading the works of Forel, its author Simon Hofmann found it difficult to comprehend the continuing veneration of the man, of which the bronze bust was an expression, ultimately seeing the latter as “a mockery of all the victims of compulsory interventions in Swiss psychiatry”. The Student Council took up the matter, bringing it to the attention of the university management in 2004. They turned to the Ethics Commission for advice on how to deal with Forel’s memory on university premises in light of his “eugenic past”. In 2005, a high-ranking colloquium grappled with the issue. There was consensus that the bust could not simply be left on display without comment. But the members also found that it should not simply “sink into oblivion, but should instead be linked to an exhibition or subjected to some form of artistic alienation and contextualised with additional information”. However, after further debate, the position changed and the bust quietly disappeared into the Canton of Zurich’s collection of artworks, where it still resides today, in storage in a warehouse in Embrach. But not on a marble pedestal.