Sexuality in the Middle Ages

If we hazard a look at the medieval era, we discover a history of sexuality that is far more multilayered than we might at first have imagined. While the Christian church sought to extend its influence into private bedchambers, ‘lascivious’ attitudes and practices stood in the way of its ambitions.

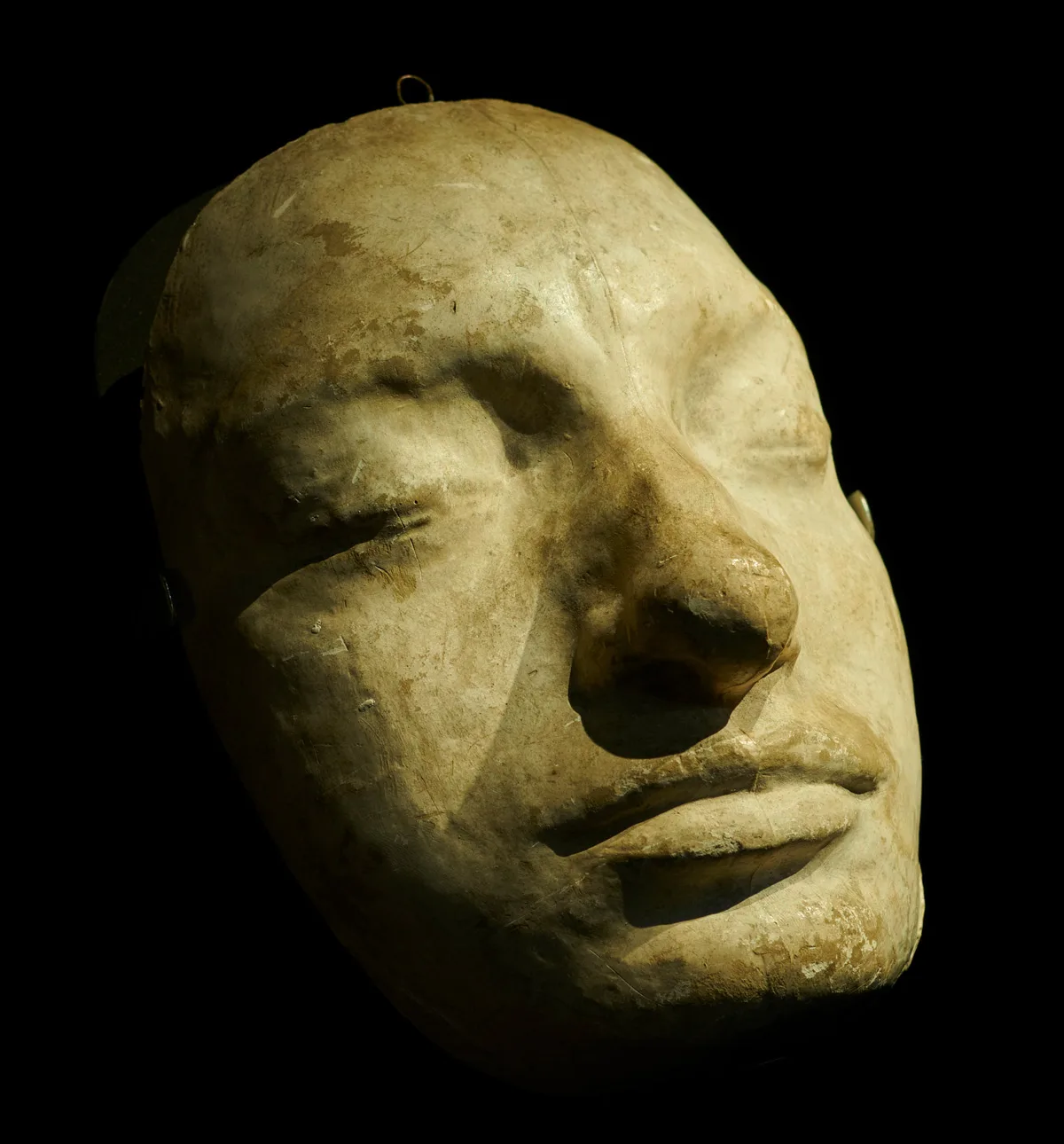

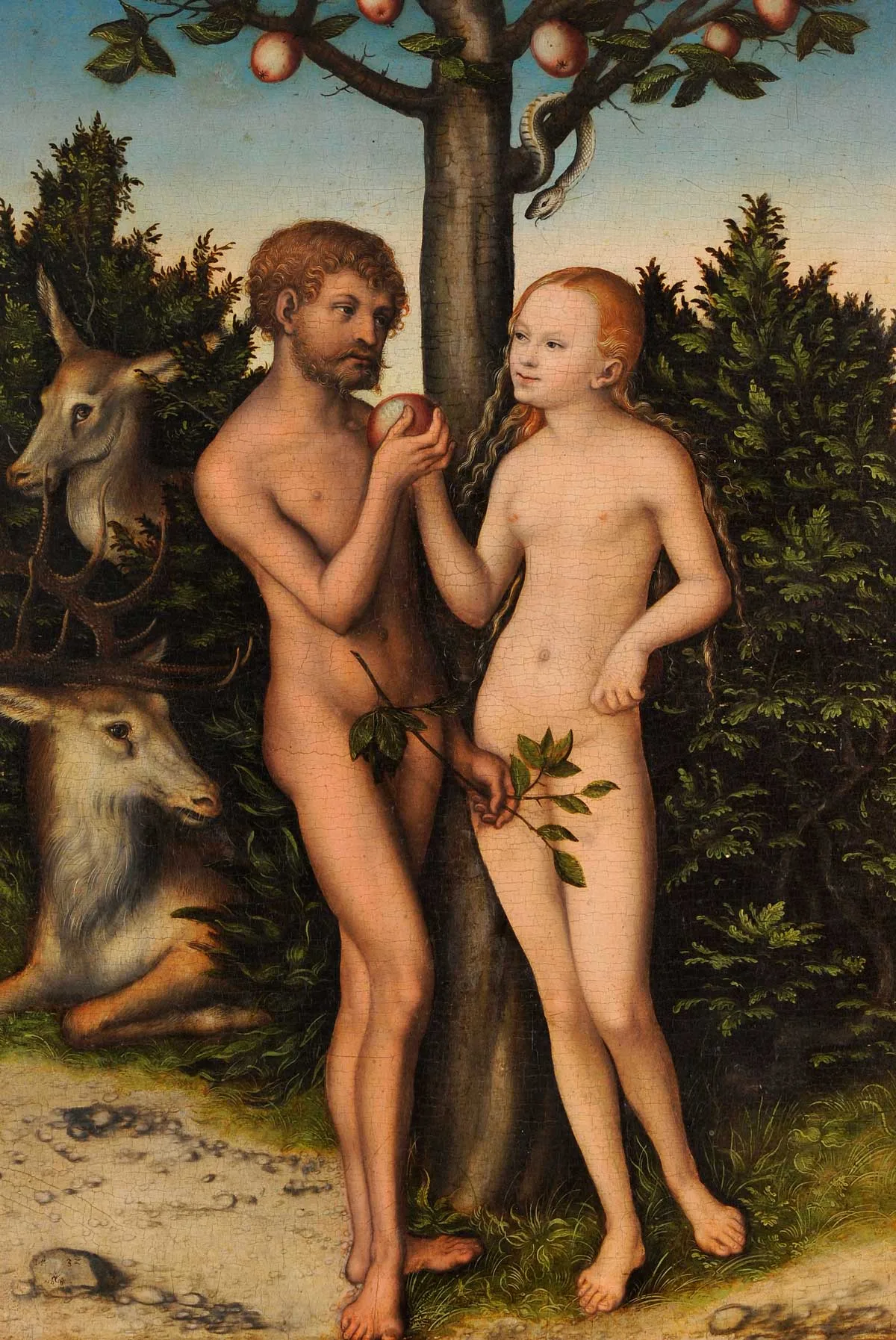

It starts with the Biblical creation narrative: with Adam and Eve, the first man and woman. The story of ‘the Fall’, or original sin, set the tone for what was to follow: women became ‘seductresses’ and men ‘the seduced’. This interpretation of Eve as temptress had serious repercussions for the image of women in general by portraying them as a ‘weak’ yet at the same time ‘seductive’ sex.

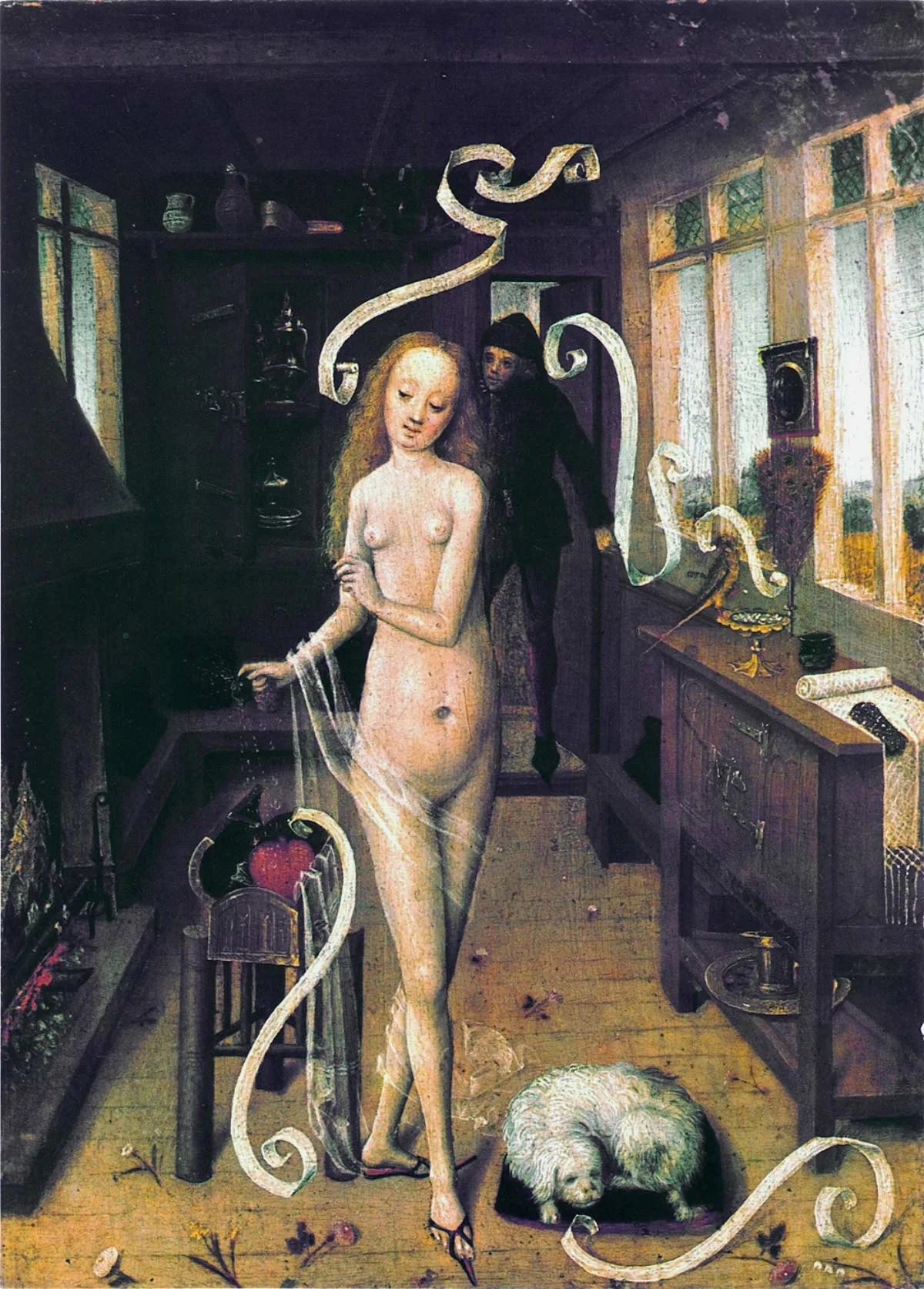

This theme is also addressed in the medieval legend of Aristotle and Phyllis: Aristotle, tutor to Alexander the Great, warns his pupil not to become distracted by the beautiful Phyllis. Disgruntled by this cautionary piece of advice, Phyllis decides to humiliate Aristotle. She seduces the philosopher, who falls for her charms and allows himself to be ridden by her like a horse. Alexander, looking on, recognises the great thinker’s weakness in the face of ‘feminine wiles’. The end of the story reeks of double standards: it both confirms Aristotle's warning about the power of love to distract while also demonstrating Phyllis’s extraordinary intelligence and agency.

Chastity v. lust – an inevitable struggle?

In this way, the female body became endowed with seemingly contradictory qualities: there was the negative association with seduction on the one hand and the positive association with abstinence on the other – depending on how the respective behaviour was judged: as sinful or virtuous.

If you must have sex, please stick to the rules!

Sexual norms and their consequences

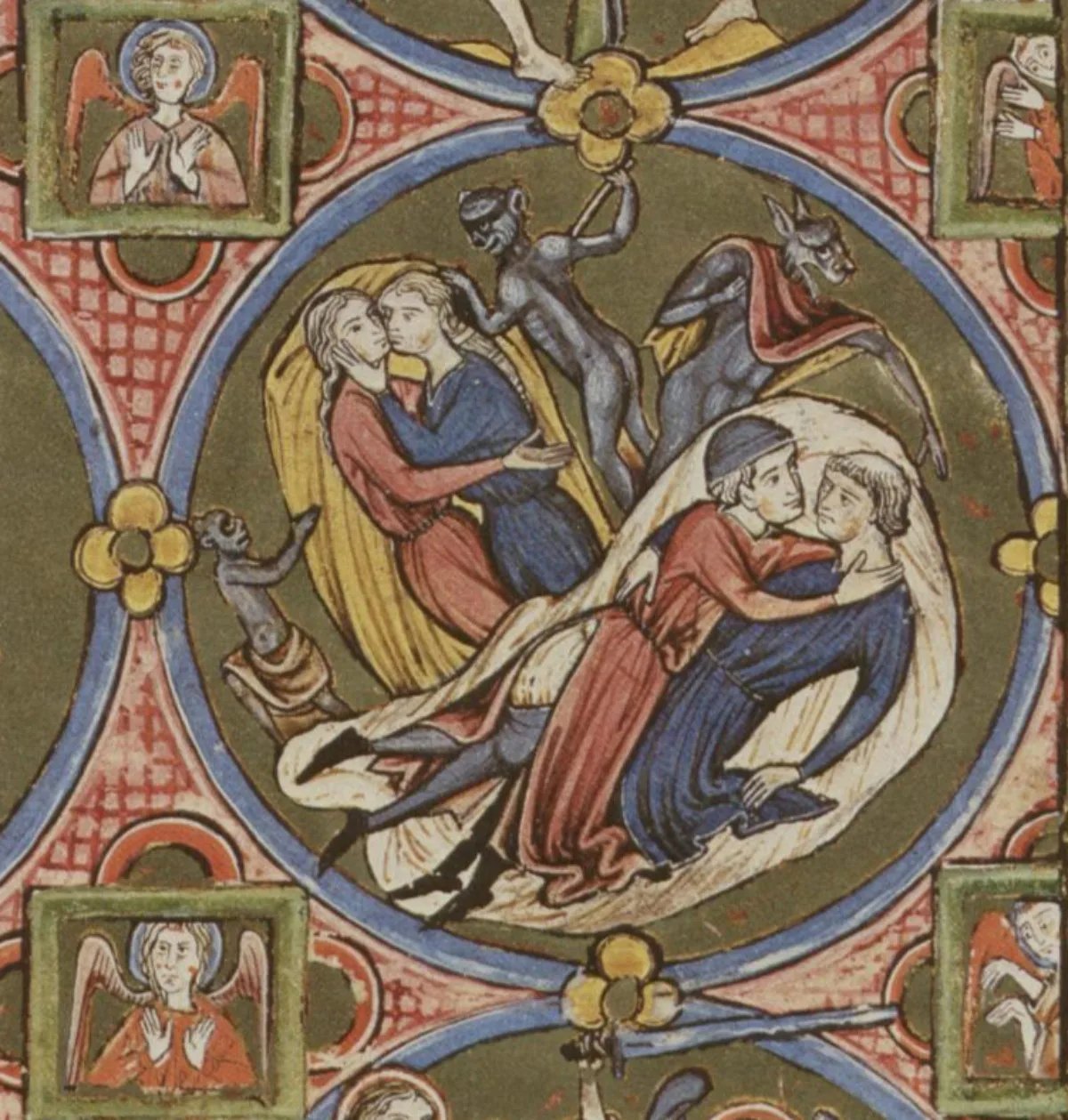

These attempts at standardisation had particularly dramatic consequences for homosexuality. While still practiced relatively openly in ancient times, Christianity condemned it as ‘unnatural’.

Prostitution: a blind spot

Moving from criticism to a medical standpoint

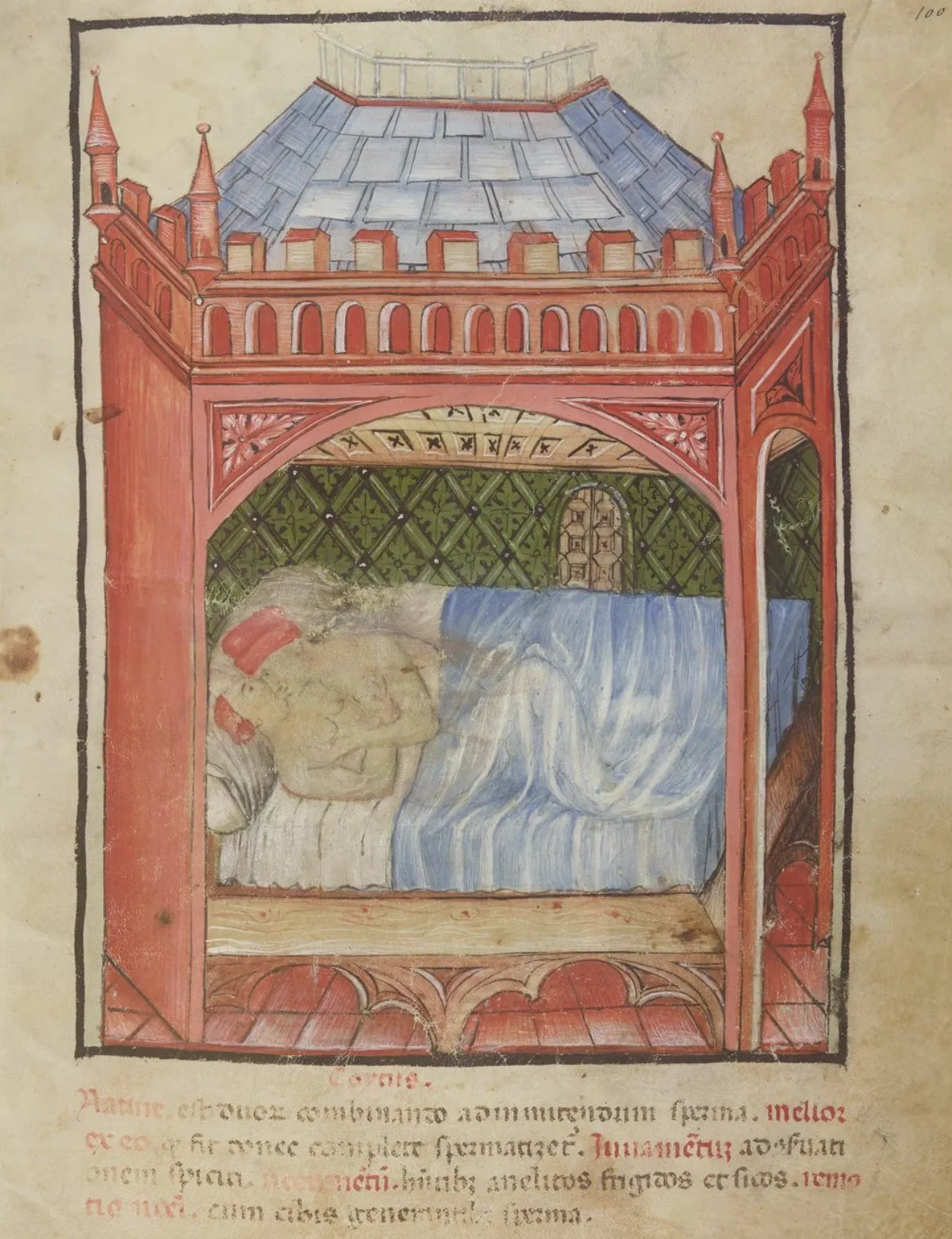

Conversely, the medical world saw masturbation, and the satisfaction of lust in general, as less of a problem. Physicians even claimed that the expulsion of bodily fluids helped balance the four ‘humours’ and maintain good health.

However, as sexual activities were seldom written about without reference to the standpoint of moral theology, many of these handbooks included detailed instructions on how to satisfy one’s sexual desire without coming into conflict with the religious angle, thus spanning the gap between medicine and religion.

There’s no smoke without fire

By virtue of their very existence, various surviving sources point to a broader spectrum of practices in real life. ‘Penitential books’, for example, were a kind of catalogue detailing the offences and setting out the penalties for each. One such book from 6th-century Ireland states that:

“A husband whose wife has lain with another man must not share his bed with his spouse again until she has done the prescribed penance, namely one full year of penance. Likewise, a wife may not seek to share a bed with her husband if he has lain with another woman until he too has done the same penance.”

In addition to strict regulations, all manner of erotic or obscene content has come down to us from the Middle Ages. For example, the badges showing crowned vulva and winged phalluses, and even ‘indecent’ stories that served as entertainment. We are surprised today by how explicit the content of such texts is, like this fabliau, a ‘Schwank’ or comic tale, by Jean Bodel:

“So it came about that the lady suppressed the thoughts and desires that she harboured towards him; she fell asleep in disappointment and anger. The lady dreamed a dream: she was at an annual fair, the likes of which you never did hear! For every table, stall, booth and shop [...] was selling not grey or coloured furs, or bolts of linen or woollen cloth [...]. Only testicles and cocks were on display! In wild profusion: [...] You could get a good one for thirty sous, and a nice, well-formed one for twenty sous. And there were even cocks for poor people: you could buy a small one for ten sous or for nine or eight. They were being sold separately and in bulk: the biggest and best were the most expensive and most closely watched over.”

Between rigid ideals and lived experience

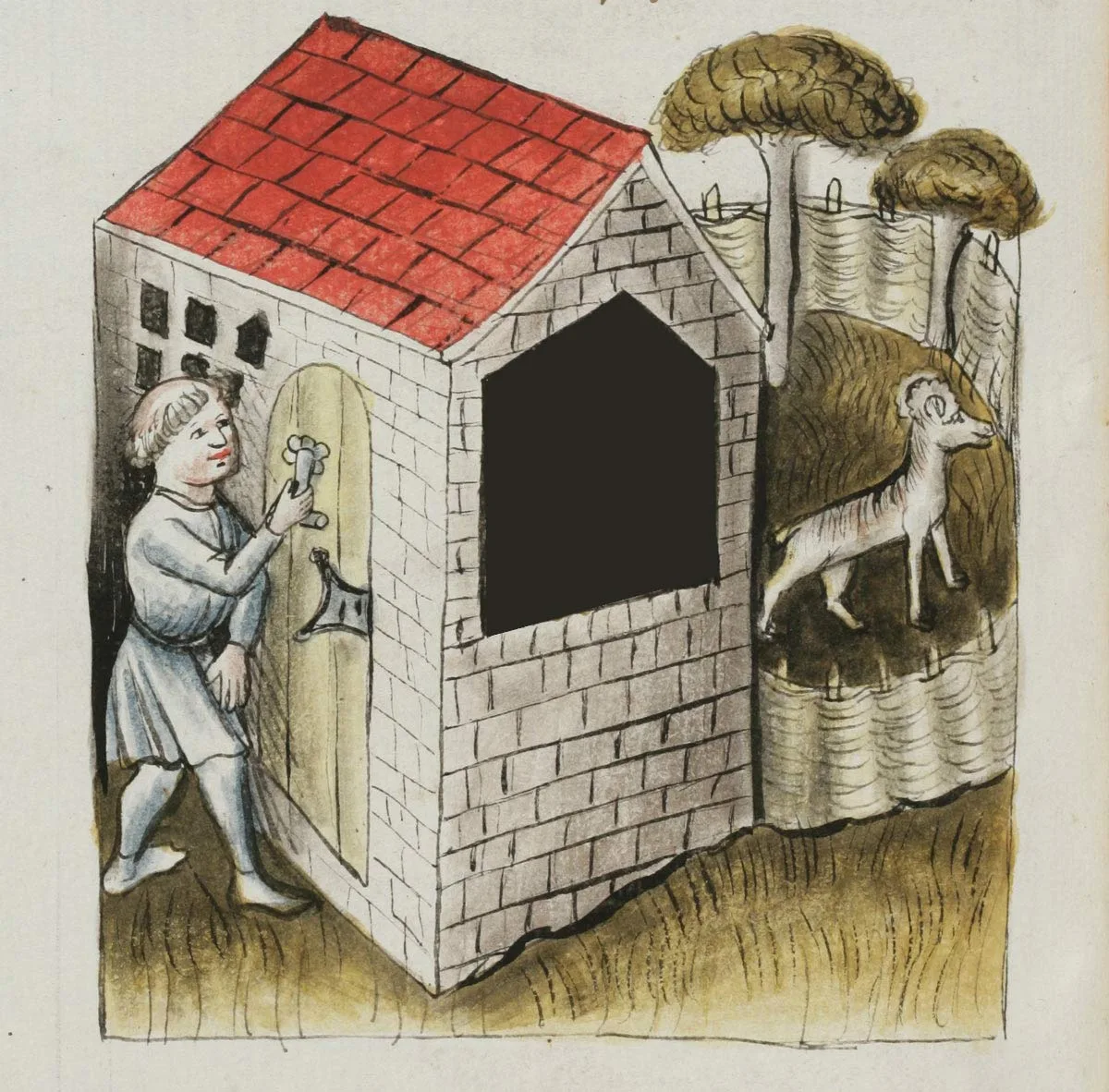

In the Middle Ages, Christian theology orchestrated a struggle between virtuous chastity and sinful lust. As the Church saw it, chastity ought to triumph and bring order to an otherwise unchaste world. But everyday life tells a different story: the Middle Ages were neither exceptionally prudish, nor exceptionally lustful. Sexuality was practiced within marriage, in moderation, in bed, between heterosexuals and with the woman playing a passive role, but also out of wedlock, in brothels, without moderation, between homosexuals, with women riding on top of men – and much more besides.

Sex as a human preoccupation

People have a tendency to interpret, evaluate or simply cultivate their bodily processes – be that digestion, the intake of food or reproduction. The reasons are no doubt many and varied: political, religious and philosophical aspirations, claims to power, social controls or quite simply an attempt to differentiate ourselves from other creatures. Whether past or present, we all have at least one thing in common: people have made sex the object of their culture.