The dream of an alpine waterway

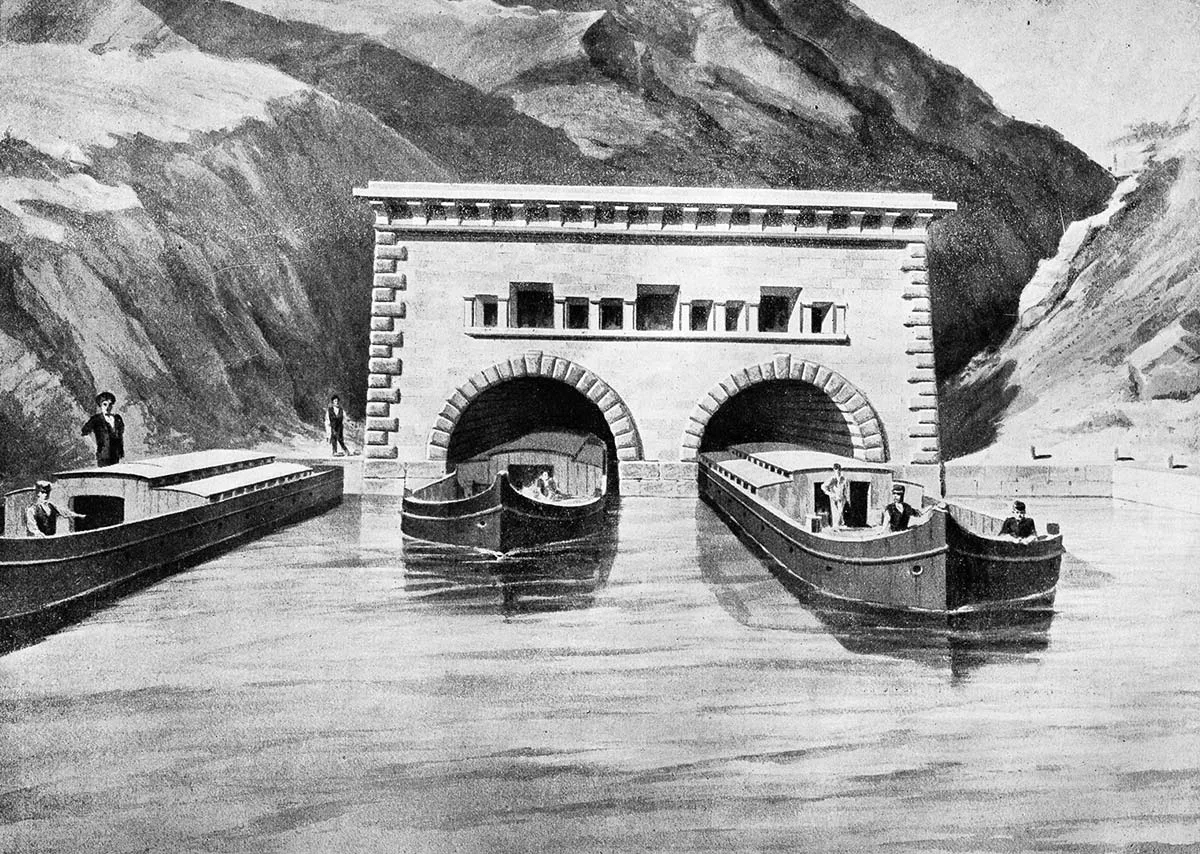

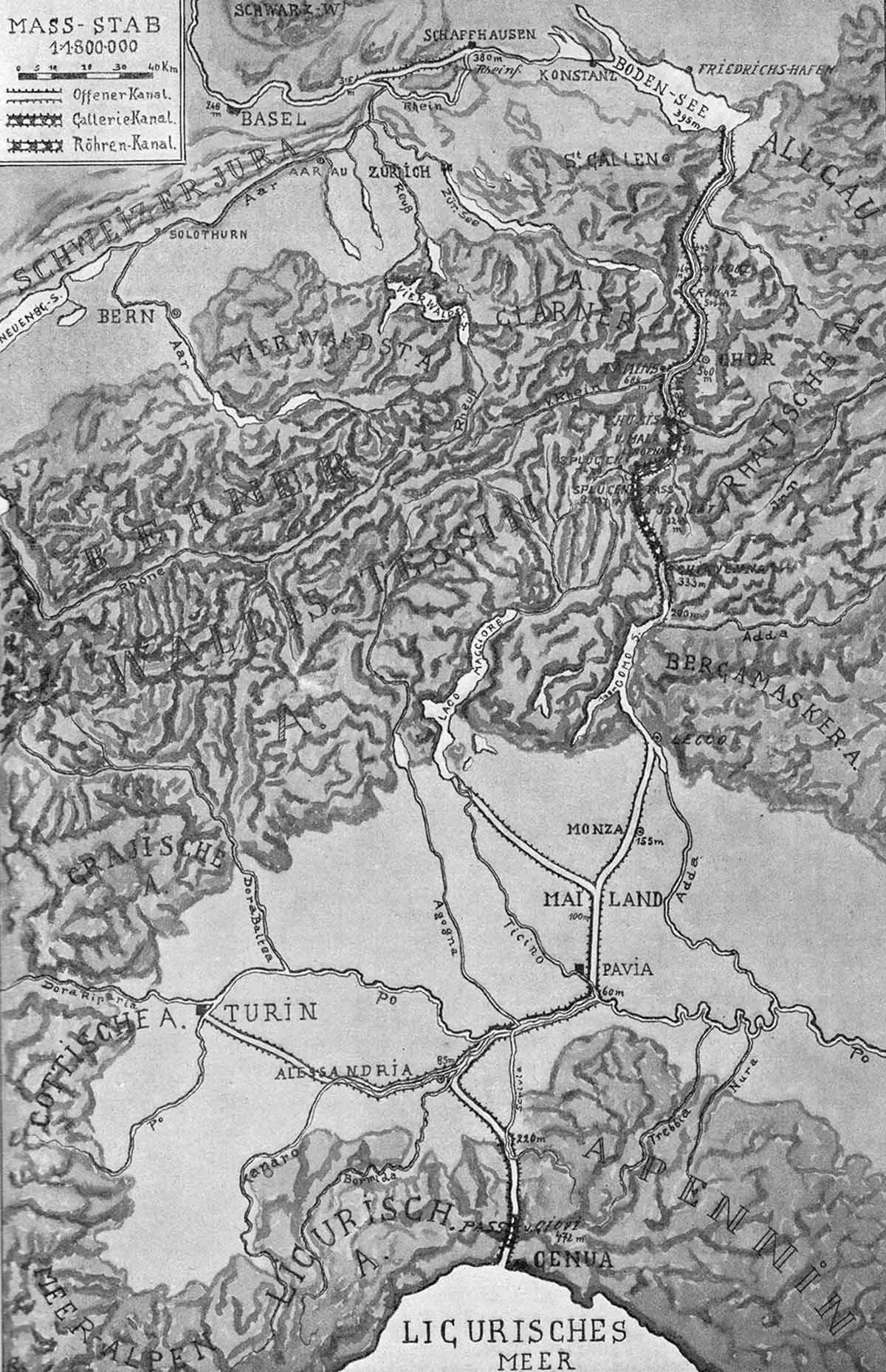

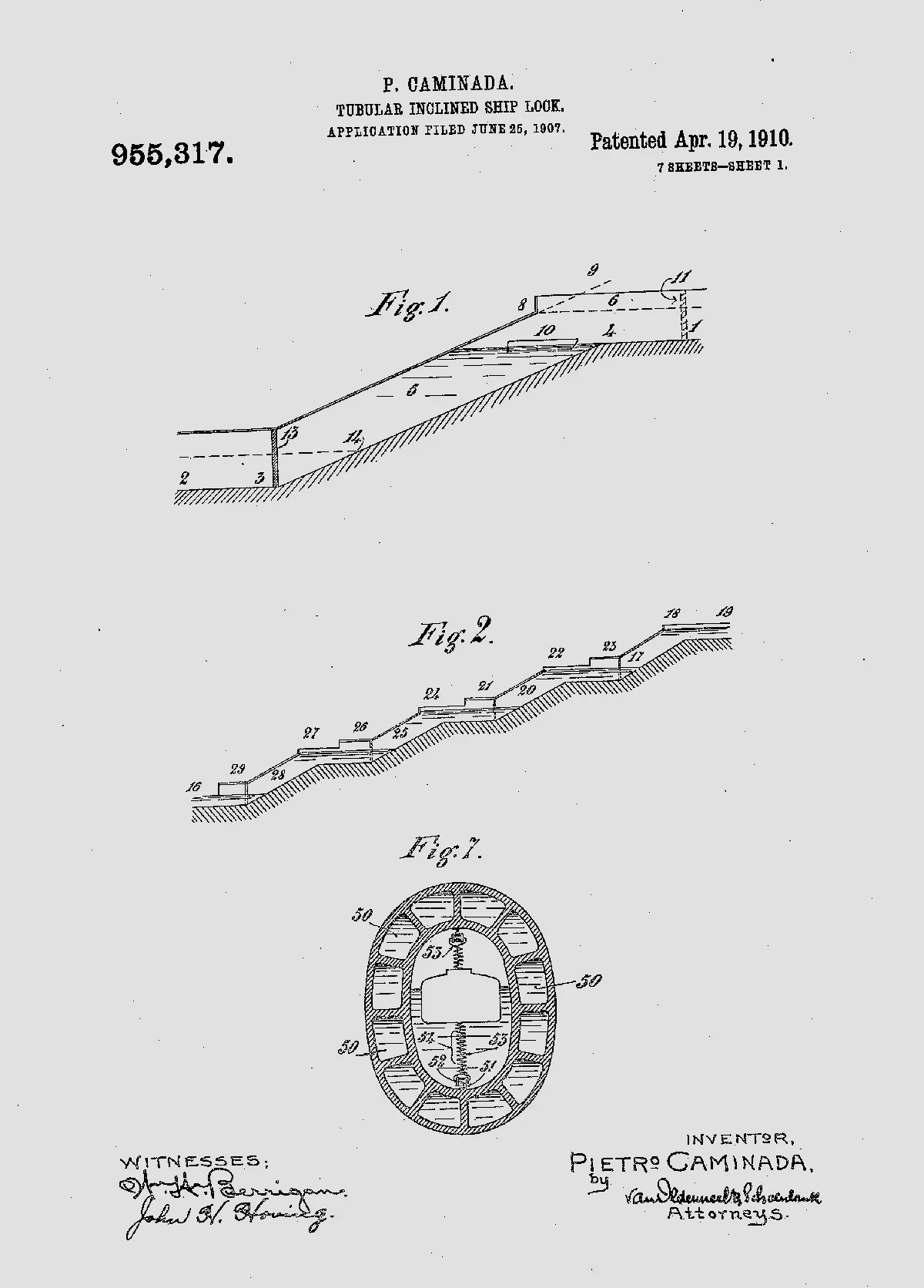

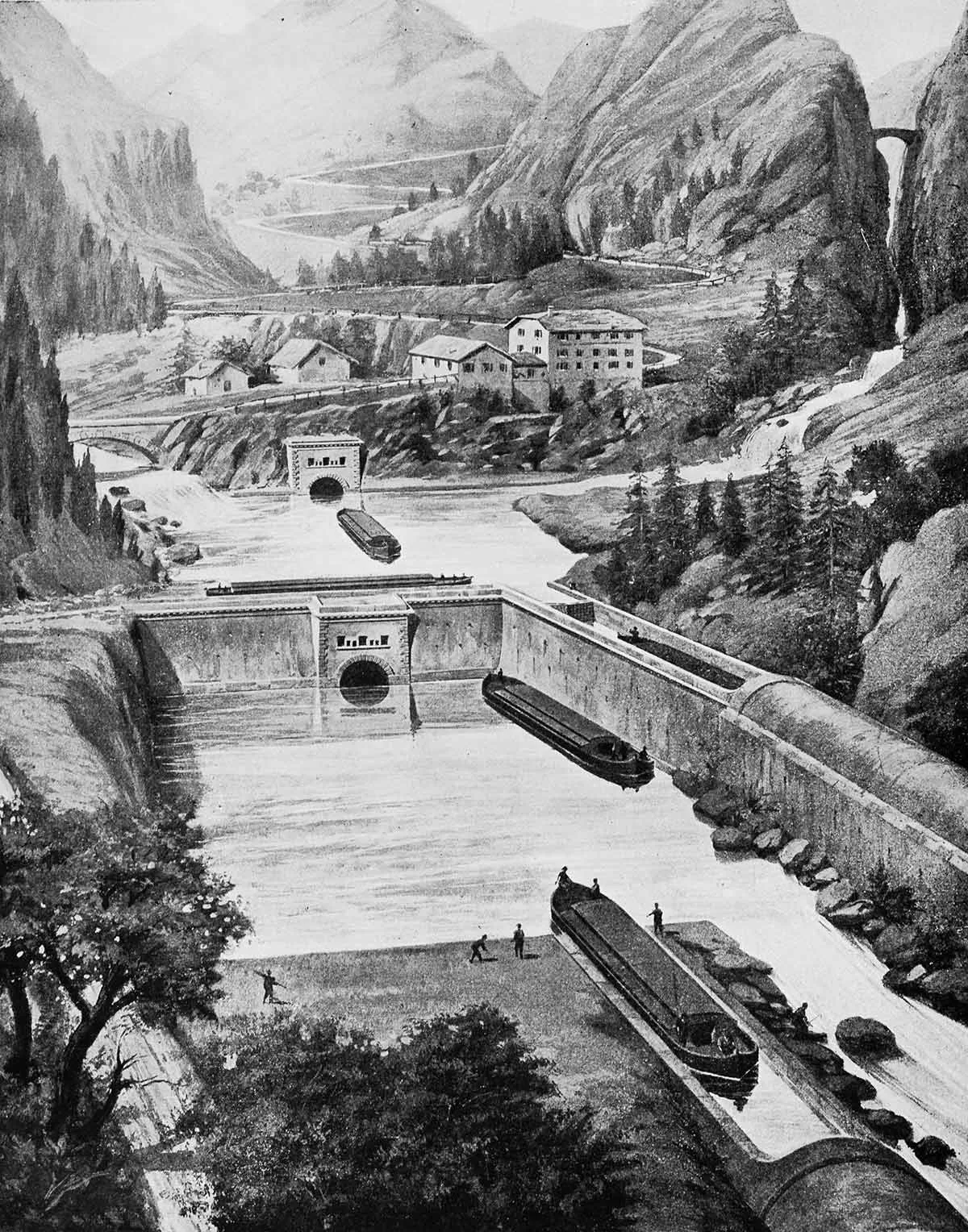

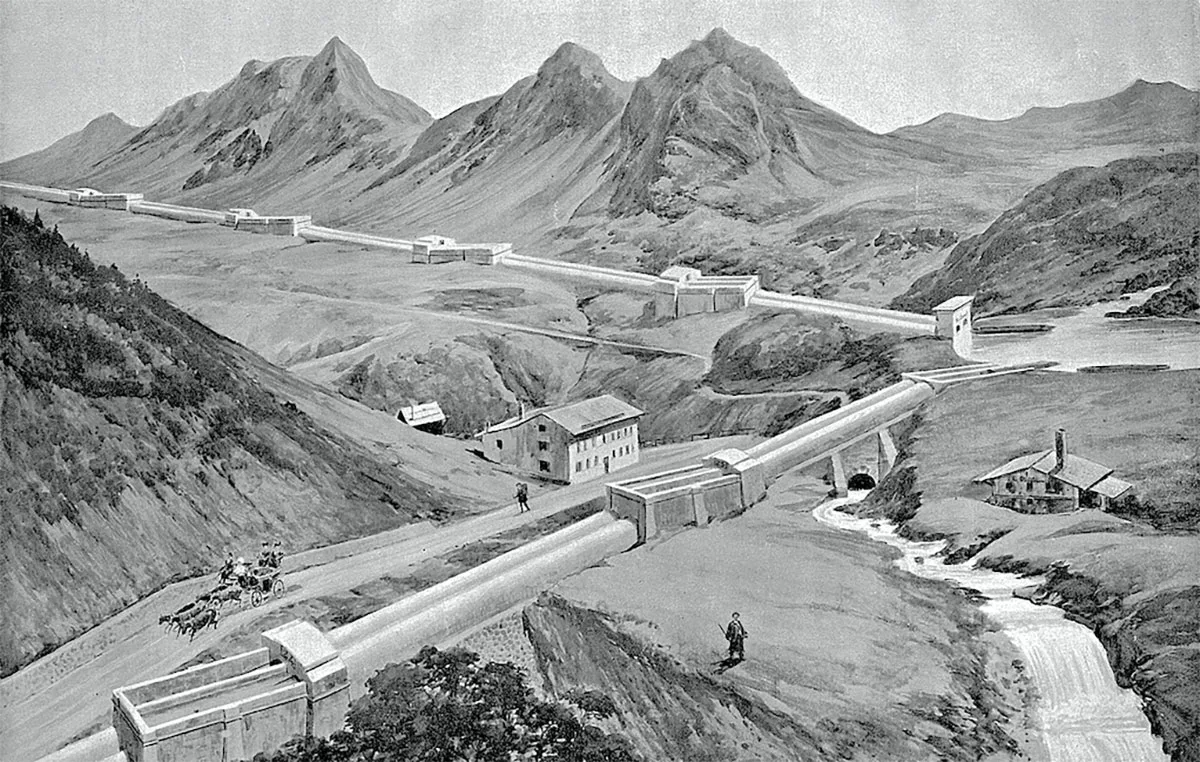

Pietro Caminada had a simple idea to turn the inconceivable into reality: huge cargo ships crossing the Alps without using self-propulsion. The stroke of genius by the engineer with Graubünden roots was a viable project – at least he thought so.

The pioneer of Brazil

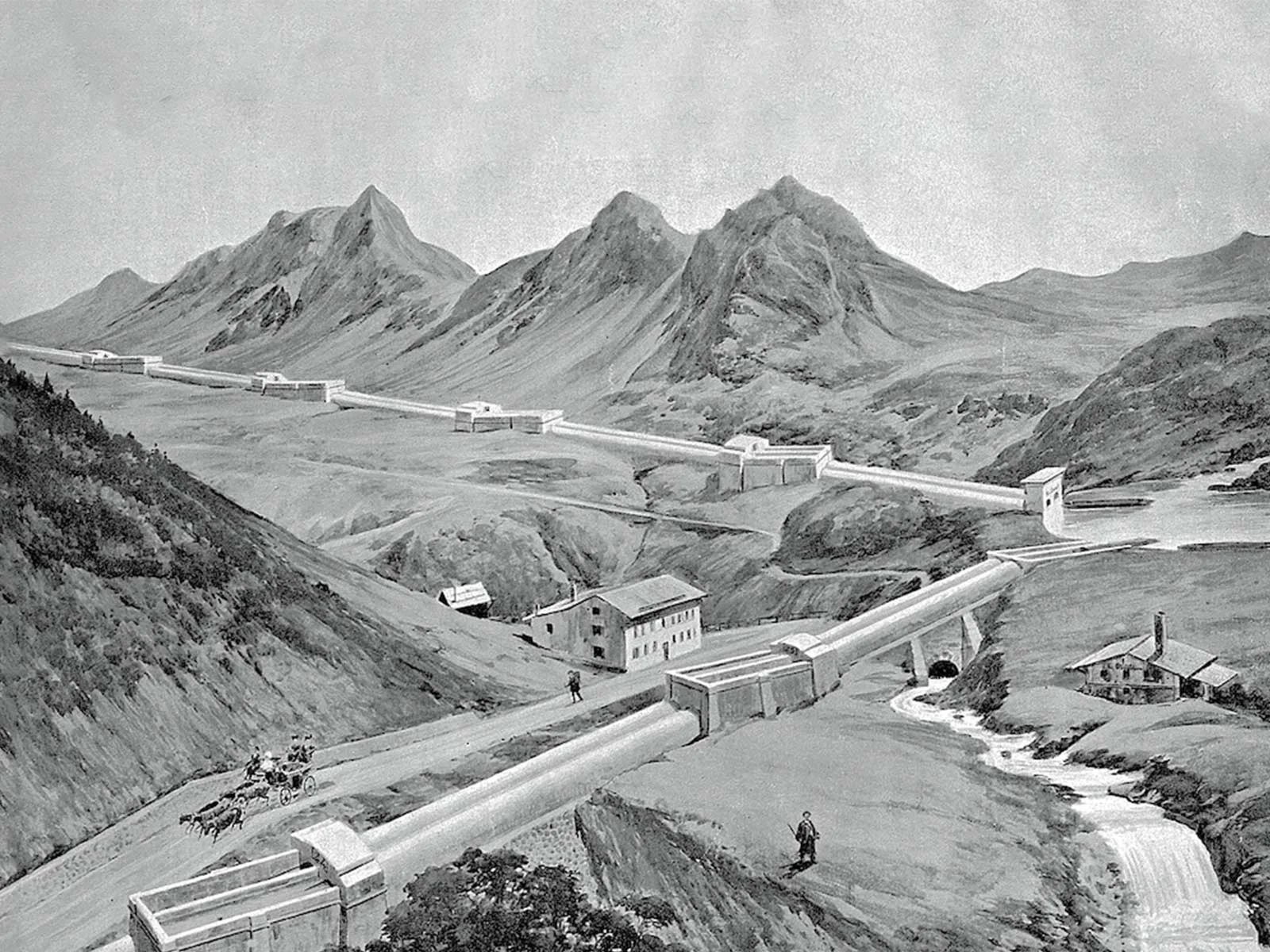

Communicating lock chambers

An audience with the king

The report did not go unnoticed. Five days later King Vittorio Emanuele III invited Pietro Caminada for a private audience in the Quirinal Palace. The monarch had him explain the project and praised the inventor. “When I am long forgotten, people will still be talking about you,” he predicted.

Neue Zürcher Zeitung was also impressed: “Caminada has managed to devise a system that Senator Colombo (...) considers practical and feasible. It is, as Colombo observes, as wonderfully simple as all great ideas.” A few days later Berliner Illustrierte lavished praise on the inventor, describing Caminada as “one of the most outstanding hydraulics engineers of our time”. The New York Times called Caminada “a man of genius”, who had given his assurance that a difficult problem had been solved by applying one of the fundamental principles of hydraulics.

“A technical fantasy”

One of the few sceptics was ETH engineer Rudolf Gelpke. “The idea is remarkable and it’s great that its feasibility will be proven through experiments”, he wrote in the Schweizerische Bauzeitung. Nonetheless, he also said he thought Caminada was a dreamer. “And up go the much vaunted lock chambers, at least on paper for now, from San Giacomo valley up to Isola, 1,247m above sea level.” The project was, argued Gelpke, economically a non-starter in every way, referring to it as a “technical fantasy”.

The plan of transalpine shipping, however, turned out to be a pipe dream. Italy was mired in economic and social difficulties and opted for colonial expansion as a diversionary tactic. In 1911, Italian troops annexed two provinces in Libya. In 1915, the country joined in the First World War. Caminada turned his attention to urban development. Around 1916, he planned to upgrade the port at Genoa, and later he worked on expanding Civitavecchia port. He designed a new area for Milan to the south of Piazza del Duomo. In Rome, he conceived a “Città Giardino” in the Montesacro district around 1920.

His ‘Via d’Acqua transalpina’ has faded into the mists of time. Now only ‘Via Pietro Caminada’ remains to remind us of the engineer. It’s a narrow country road with cracked asphalt between Rome and the Tyrrhenian Sea. It almost forms a full circle and doesn’t really lead anywhere.