The Büsingen Affair

Schaffhausen was the scene of some serious sabre-rattling between Hessian soldiers and Swiss troops in July 1849. It took cool-headedness and negotiating skill to avoid a bloody conflict.

Büsingen, with a surface area of 7.62 square kilometres, is located on the right-hand side of the Rhine. It was originally part of the Principality of Würtemberg and from 1810 the Grand Duchy of Baden (now the German state of Baden Würtemberg). On the right-hand side of the Rhine, Büsingen is completely surrounded by the Swiss canton of Schaffhausen without any direct access to the rest of Germany, while on the left side it borders the cantons of Thurgau (Diessenhofen) and Zurich (Feuerthalen).

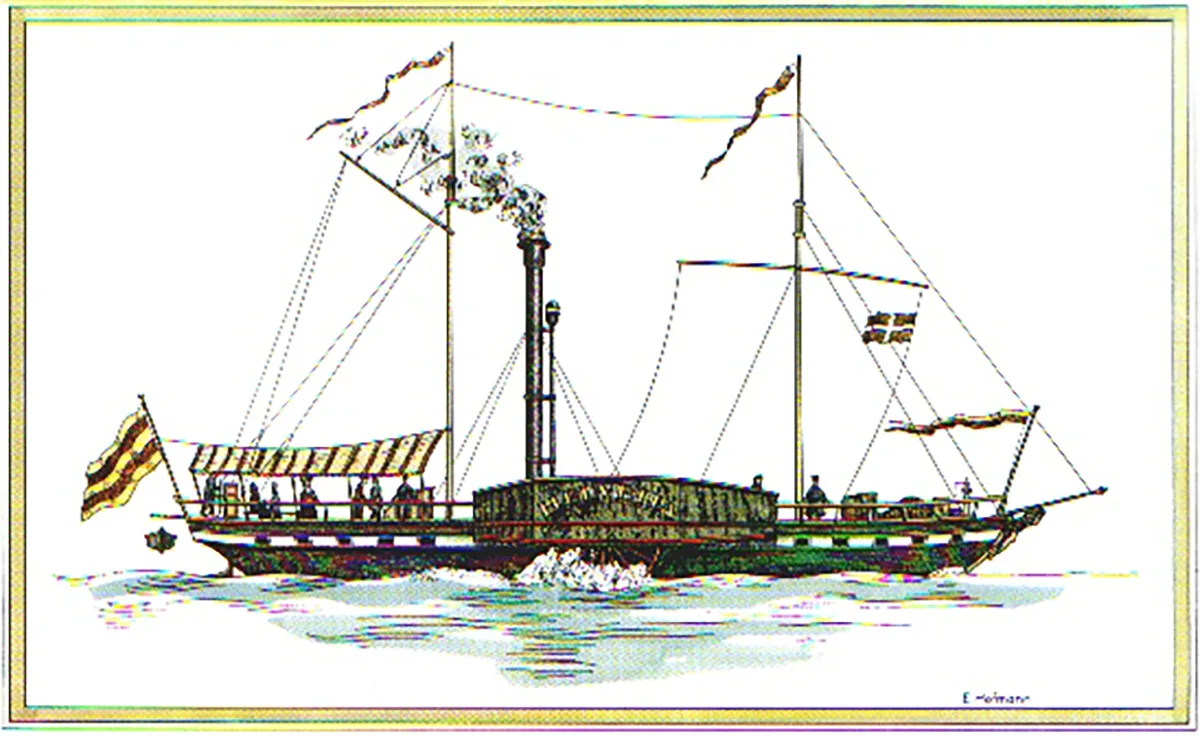

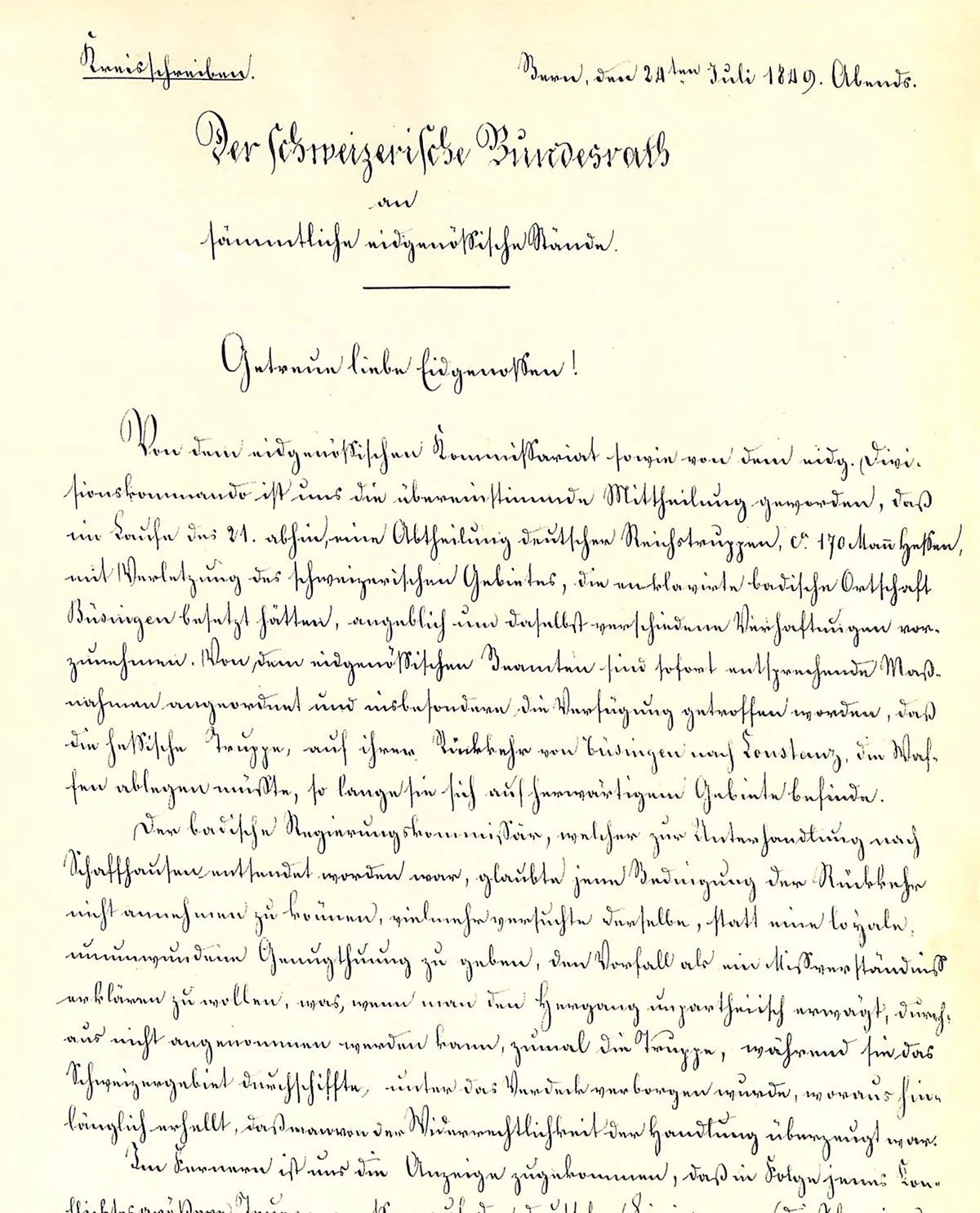

After the Baden Revolution had been suppressed by German federal troops under the leadership of Prussia, on 21 July 1849, the 170-strong Hessian company Stockhausen boarded the Badenese flush-deck steamer named Helvetia, which had operated on Lake Constance between 1832 and 1843. The soldiers were to conduct a punitive expedition in Büsingen to quash suspected revolutionary activities. The small army travelled down the Rhine in the early hours of the morning without seeking permission from or notifying the Swiss authorities. When they passed through Stein am Rhein, the ‘invasion’ went unnoticed as the men were hiding under a deck, which was later interpreted as conscious deception. The troops landed in Büsingen at 7am, occupied the village, disarmed citizens and arrested three men: Walter, the municipal treasurer; von Ow, the doctor; and Güntert, the vet. Walter and von Ow soon had to be released as there was no incriminating evidence against them. Güntert, on the other hand, was taken aboard as a prisoner and guarded. At 1pm, the steam ship was meant to set sail again. But it didn’t.

That evening, the troops in Büsingen were permitted to send two envoys to report to Constance. It emerged that the journey to Büsingen had been ordered by civilian authorities. The troops were unaware that they had crossed a border, or to be more precise, ferried over it by water. Once again the following day, the Swiss refused to grant permission for the blockaded company to retreat by steam ship.

The Swiss army on standby

The negotiations were unsuccessful at first. The Swiss brigade commander, Colonel Franz Müller from Zug, demanded that the Hessians drop their weapons to retreat across Swiss territory. They refused to yield to the demand though, citing incompatibility with military honour. The negotiations stalled as both sides doubled down on their demands. Only after a formal apology from the German federal army was issued by the Hessian Staff Major Ferdinand du Hall could discussions be resumed.

Two-and-a-half Swiss infantry companies and a cavalry company were supposed to escort the Hessians across Swiss territory to Gailingen. However, the Hessian troops, who were unfamiliar with the route, marched on the road towards Randegg and were stopped by Swiss reserve troops at the border. Once the Swiss accompanying troops had been summoned and arrived, the Hessians marched onwards, via Dörflingen, taking a detour to eventually reach Gailingen. Meanwhile, the steam ship Helvetia was taken back to Constance under Swiss convoy, bearing the Swiss flag and accompanied by two Swiss officers.

The negotiations allowed the Büsingen Affair to be resolved without bloodshed or loss of face on either side. Troop numbers on both sides of the border were significantly cut back as a result.