Switzerland’s ‘War of Sticks’ of 1802

The battle over freedom and liberties led to a game-changing civil war in Switzerland in the early 19th century.

The unpopular Republic

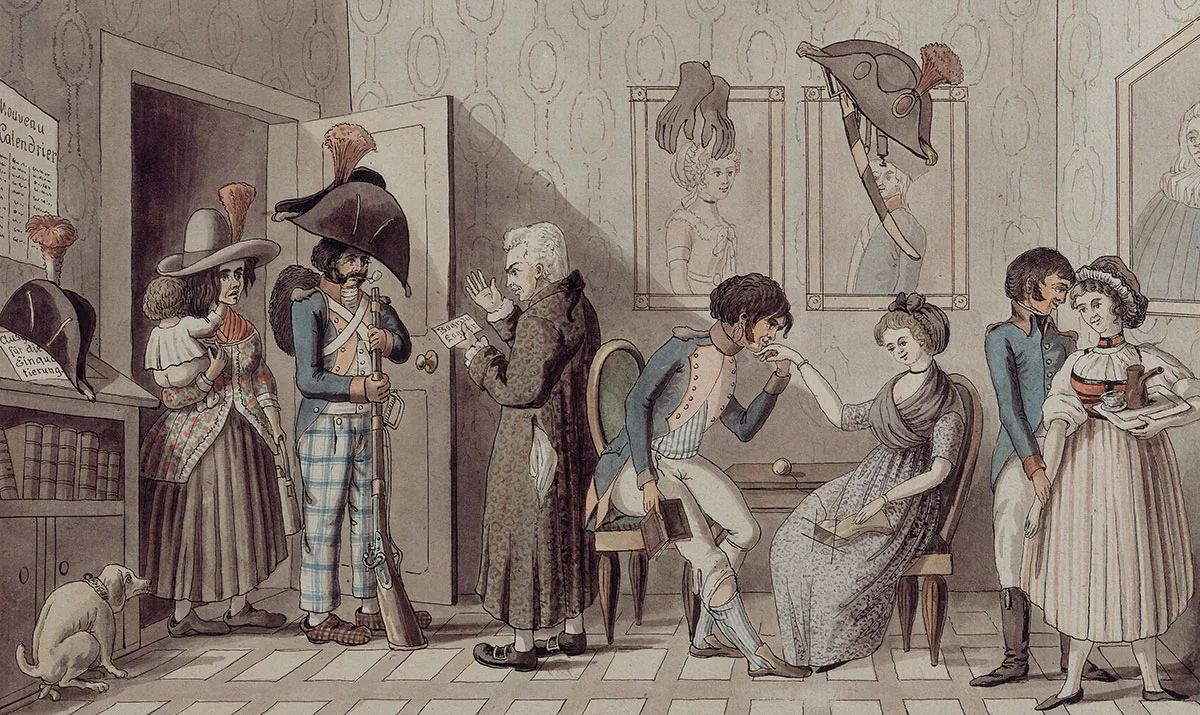

In towns and in the countryside, the presence of French troops was expensive and annoyed the local population. Caricatures by David Hess-Hirzel. Swiss National Museum

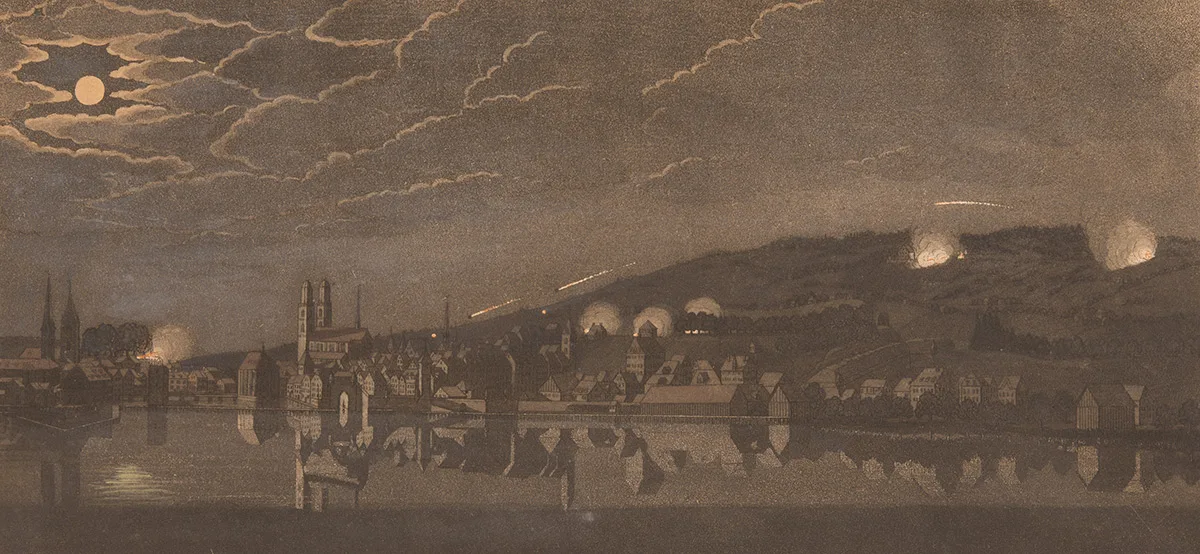

Outbreak of civil war

Did the fall of Bern mean the collapse of the Republic?