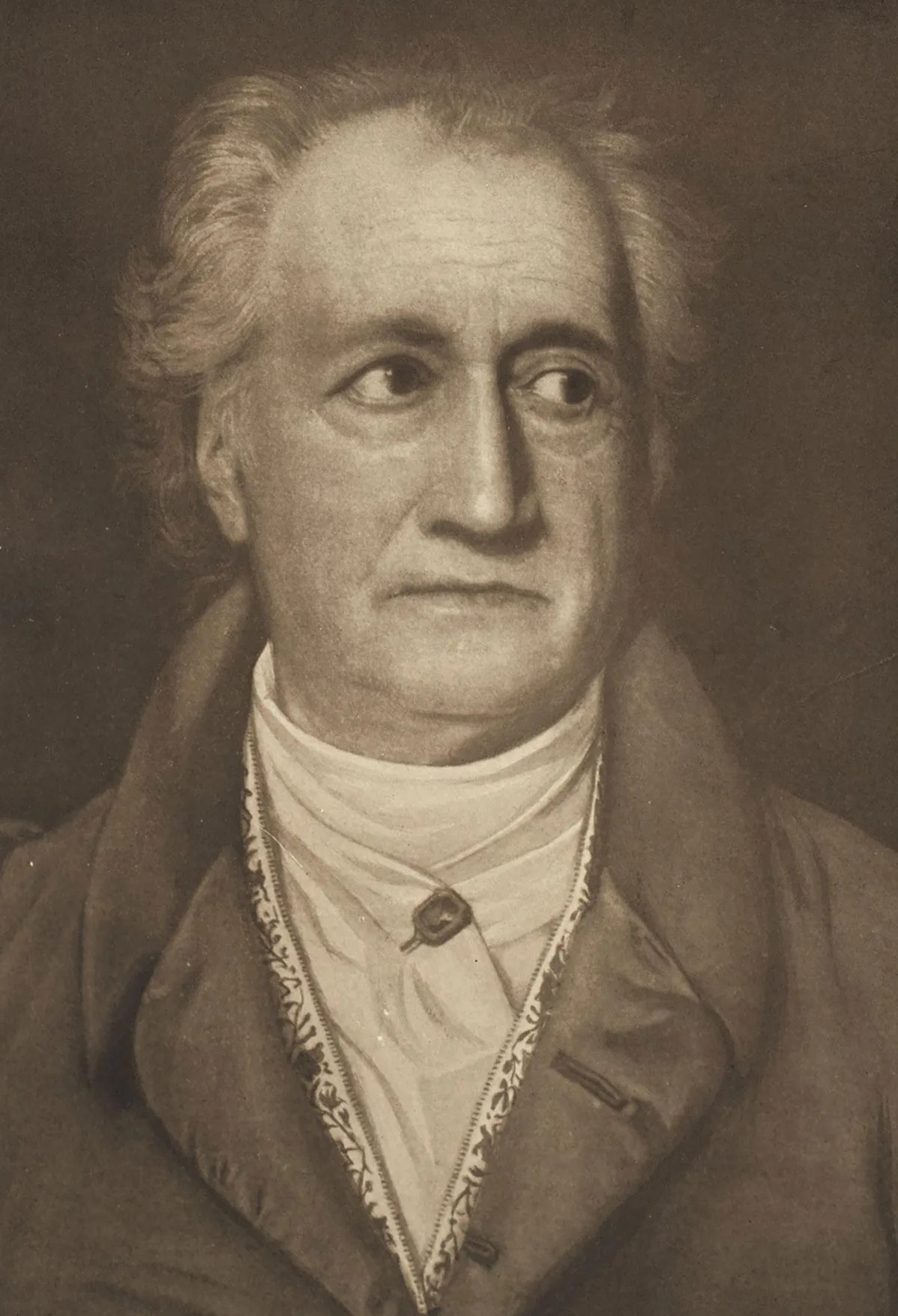

The famous mountain doctor from Emmental

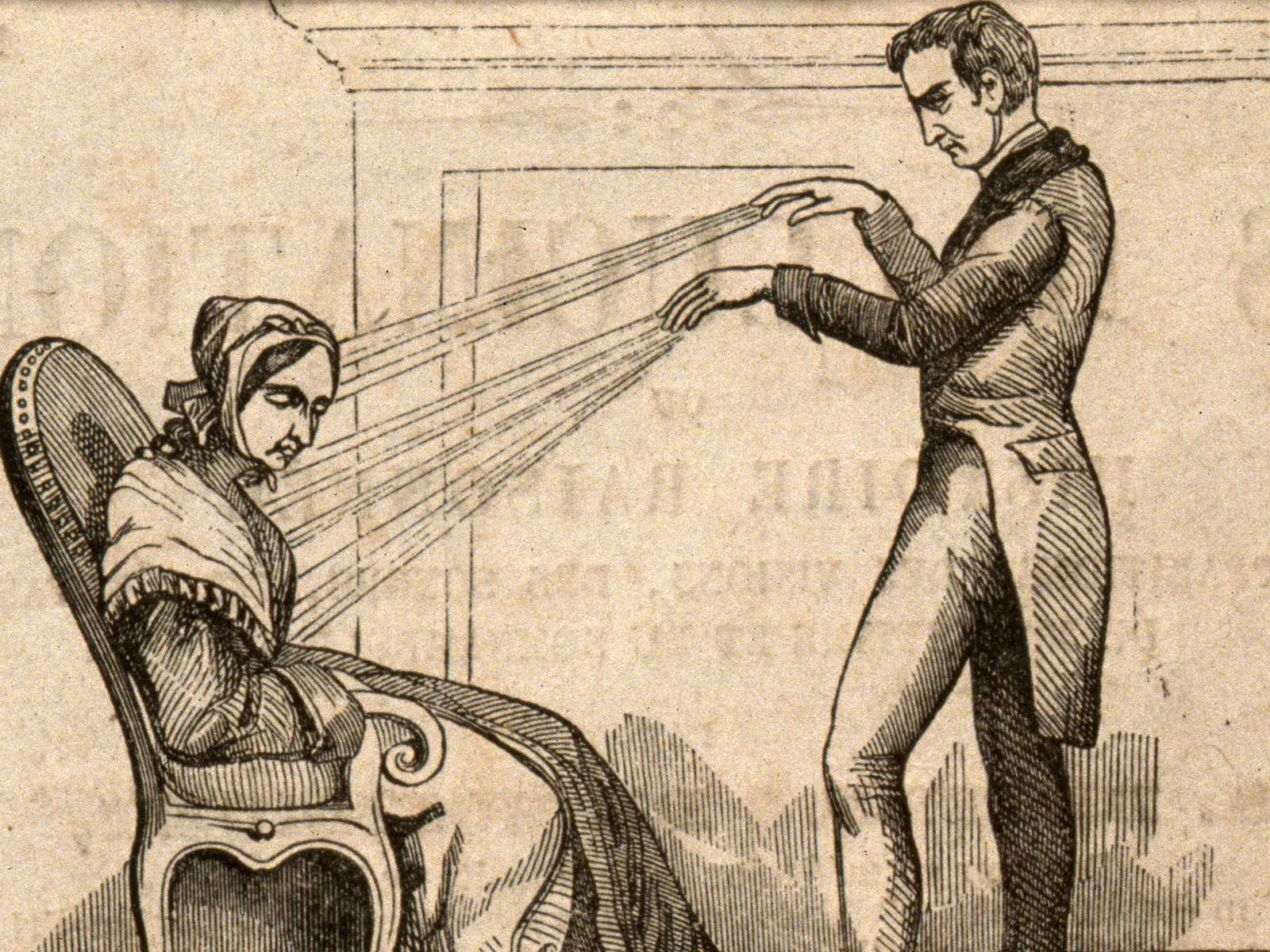

Through his sometimes unconventional methods, Michael Schüppach made a name for himself as a barber-surgeon well beyond the Emmental region.

The role of the barber-surgeon

From as early as the Middle Ages, barber-surgeons were medically trained to treat wounds and diseases, as well as shaving, hair cutting and personal grooming. The services of barber-surgeons were so in demand that they were often called on to treat soldiers during wartime. However, the quality of training varied according to the knowledge of teachers and the talent and ambition of students.

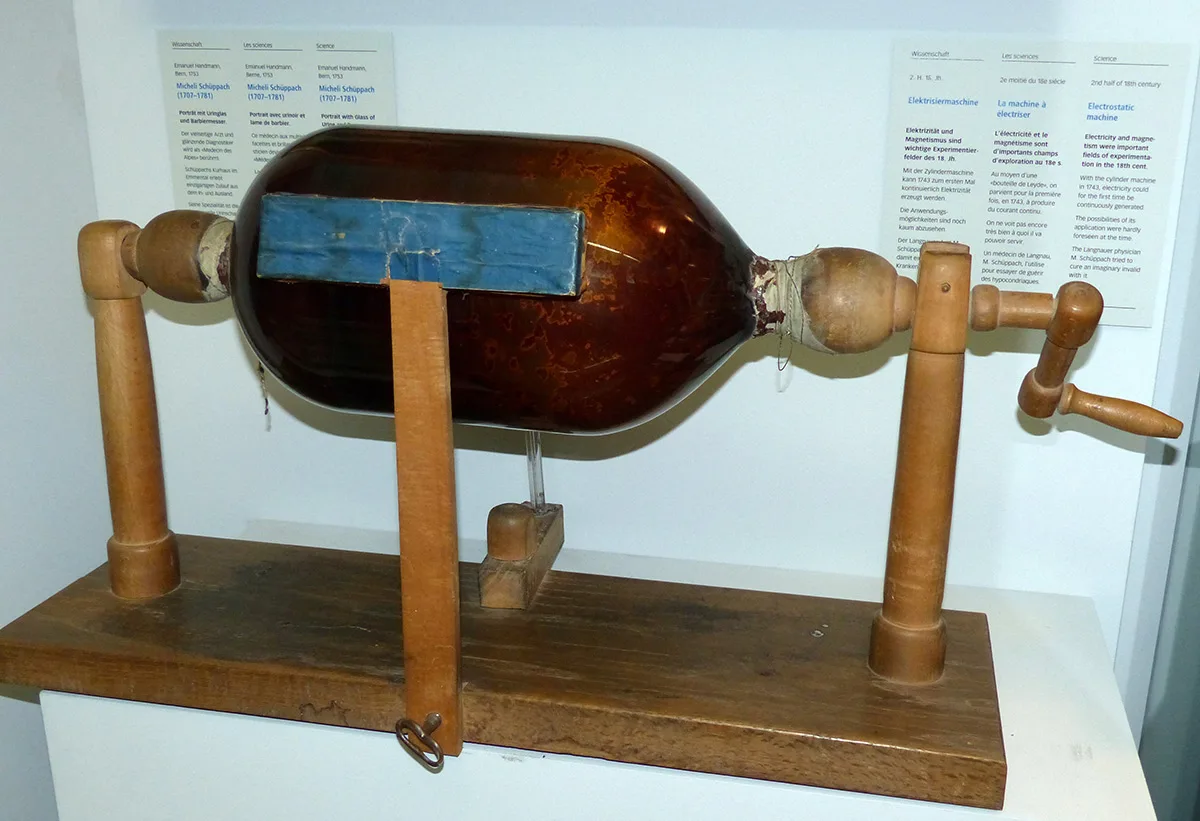

Between chemistry and natural healing

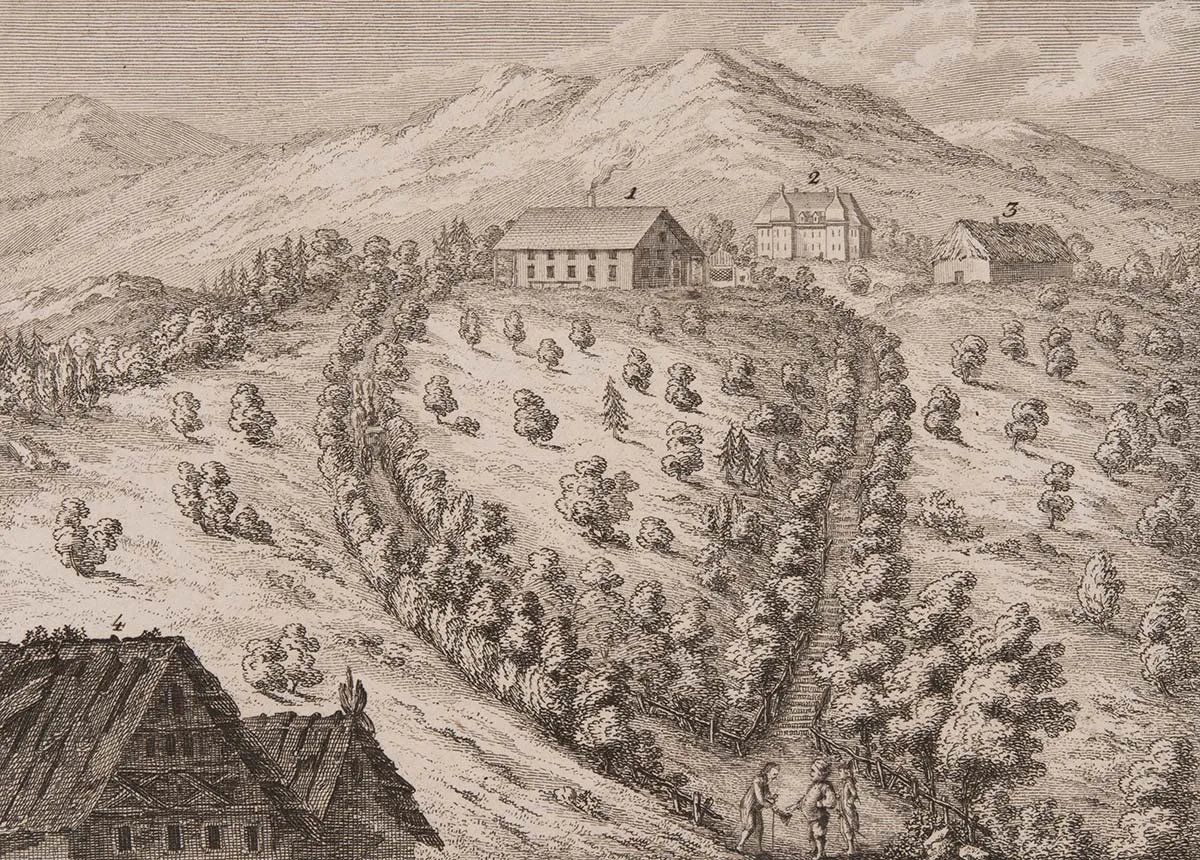

A trailblazer for tourism